Thank You, Science: The Eternal Question, “What Came First, The Chicken Or The Egg?” Is Finally Answered

What came first: the chicken or the egg? This philosophical question has been perplexing humans for ages. If the egg came first, who laid it? And if the chicken came first, how did it grow up without once being an egg?

Well, you can finally stop arguing with your relatives, pandas, because scientists say they’ve cracked the case. According to researchers at the University of Bristol and Nanjing University in China, the age-old question has finally been answered: chickens came first!

The question of whether the chicken or the egg came first has been hotly debated for centuries

Image credits: Polina Tankilevitch (not the actual photo)

But scientists at the University of Bristol and Nanjing University say they’ve finally cracked the case

Image credits: Quang Nguyen Vinh

According to the researchers, early reptilian ancestors of chickens were around before they evolved to be able to lay eggs

Image credits: KH Tan

When it comes to the philosophical dilemma of whether chickens or eggs came first it seems that humans have been talking in circles about the issue for centuries. Aristotle wrote in the fourth century BCE that the issue was an “infinite sequence” that we could never find an answer to. Greek philosopher Plutarch again posed the question in his essay ‘The Symposiacs’ in the first century CE, referring to it as a “great and weighty problem.” And while many people found the debate to be trivial, Macrobius noted in the fifth century CE that it should actually “be regarded as [a topic] of great importance. Flash forward to the 21st century, and we’ve still been unable to come to a consensus on the issue. Perhaps until now.

The groundbreaking study, ‘Extended embryo retention and viviparity in the first amniotes’, was published on June 12, 2023, in Nature Ecology & Evolution. Researchers studied 51 fossil species and 29 living species, some of which were oviparous, or lay eggs, and some of which were viviparous, or give birth to live young. According to a press release from the University of Bristol, the scientists’ findings revealed that “all the great evolutionary branches of Amniota, namely Mammalia, Lepidosauria (lizards and relatives), and Archosauria (dinosaurs, crocodilians, birds) reveal viviparity and extended embryo retention in their ancestors.”

Before the eggs came about, these reptilians gave birth live young

Image credits: Jakub Kapusnak

“Extended embryo retention (EER) is when the young are retained by the mother for a varying amount of time, likely depending on when conditions are best for survival,” the press release continued. “While the hard-shelled egg has often been seen as one of the greatest innovations in evolution, this research implies it was EER that gave this particular group of animals the ultimate protection.”

In other words, some animals that we’ve always known to lay eggs, rather than give birth to live young, weren’t always able to do that. So chickens were here before they had eggs. “Before the amniotes, the first tetrapods to evolve limbs from fishy fins were broadly amphibious in habits,” Professor Michael Benton from the Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences explained. “They had to live in or near water to feed and breed, as in modern amphibians such as frogs and salamanders.”

“When the amniotes came on the scene 320 million years ago, they were able to break away from the water by evolving waterproof skin and other ways to control water loss,” Professor Michael Benton continued. “But the amniotic egg was the key. It was said to be a ‘private pond’ in which the developing reptile was protected from drying out in the warm climates and enabled the Amniota to move away from the waterside and dominate terrestrial ecosystems.”

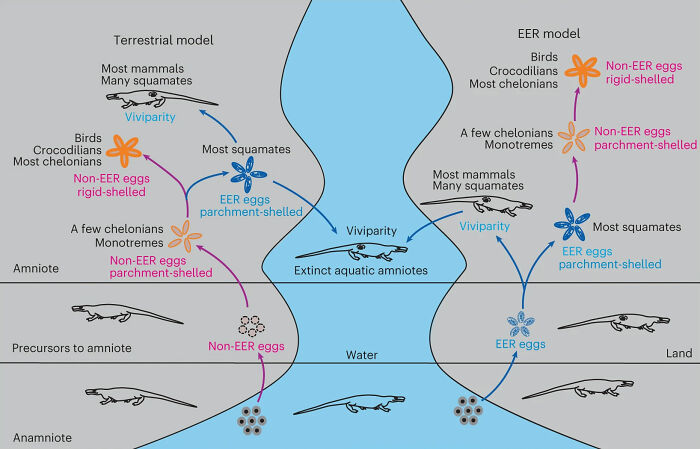

Here is a demonstration of the two competing theories for the evolution of the amniotic egg

Image credits: nature

But now, these widely accepted truths are being challenged. In fact, some species can even flip back and forth between being oviparous or viviparous and decide when exactly they want to release their young. “Sometimes, closely related species show both behaviors, and it turns out that live-bearing lizards can flip back to laying eggs much more easily than had been assumed,” Project Leader Professor Baoyu Jiang says.

“Also, when we look at fossils, we find that many of them were live-bearers, including the Mesozoic marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs,” Dr Armin Elsler chimed in. “Other fossils, including a choristodere from the Cretaceous of China show the to-and-fro between oviparity and viviparity happened in other groups, not just in lizards.”

Apparently, some species have also been able to switch back and forth between laying eggs and birthing live young

Image credits: Pixabay

“EER is widespread among vertebrates today, where the developing young are retained by the mother for a lesser or greater span of time,” Dr Joseph Keating explained. “EER is common and variable in lizards and snakes today. Their young can be released, either inside an egg or as little wrigglers, at different developmental stages, and there appears to be ecological advantages of EER, perhaps allowing the mothers to release their young when temperatures are warm enough and food supplies are rich.”

“Our work, and that of many others in recent years, has consigned the classic ‘reptile egg’ model of the textbooks to the wastebasket,” Professor Benton says. “The first amniotes had evolved extended embryo retention rather than a hard-shelled egg to protect the developing embryo for a lesser or greater amount of time inside the mother, so birth could be delayed until environments become favorable.”

“Whether the first amniote babies were born in parchment eggs or as live, snapping little insect-eaters is unknown, but this adaptive parental protection gave them the advantage over spawning earlier tetrapods.” So there you have it folks: it appears the chicken really did come first!

Readers have shared their thoughts on this discovery, making it clear that the debate still may not be settled for good

LOL at that one comment "God created chicken. Chicken laid egg." Got to love that in an article that literally references science and research, one of Big Sky Daddy's pet crazies always comes out of the woodwork. Edit: woo downvoted! I love when Christians get offended at someone daring to make fun of their precious religion XD

The whole question what came first the chicken or the egg? Is a religious question if you said chicken you believed God created the animals at adulthood if you said egg then you believed in evolution.

Load More Replies...Clearly the egg came first. There was a creature evolving that was 99.999999% chicken, and it had an egg that was 100% chicken. Tada. It's not remotely difficult. How is it still a question?

But is a chicken egg an egg that contains a chicken, or an egg laid by a chicken? :P

Load More Replies...Jesus H. tap-dancing Christ on a crutch, creationists are effing stupid.

Jesus also said: "Put this part of my body in your mouth, and wash it down with my sacred fluids." He inspired priest for 2000+ years

Load More Replies...LOL at that one comment "God created chicken. Chicken laid egg." Got to love that in an article that literally references science and research, one of Big Sky Daddy's pet crazies always comes out of the woodwork. Edit: woo downvoted! I love when Christians get offended at someone daring to make fun of their precious religion XD

The whole question what came first the chicken or the egg? Is a religious question if you said chicken you believed God created the animals at adulthood if you said egg then you believed in evolution.

Load More Replies...Clearly the egg came first. There was a creature evolving that was 99.999999% chicken, and it had an egg that was 100% chicken. Tada. It's not remotely difficult. How is it still a question?

But is a chicken egg an egg that contains a chicken, or an egg laid by a chicken? :P

Load More Replies...Jesus H. tap-dancing Christ on a crutch, creationists are effing stupid.

Jesus also said: "Put this part of my body in your mouth, and wash it down with my sacred fluids." He inspired priest for 2000+ years

Load More Replies...

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

69

27