I remember the first time I met the interrupters. I nervously drove through the streets of Hanover Park, a suburb on the Cape Flats in Cape Town, notorious for gang violence. As I drove deeper into the heart of Hanover Park I pass blocks of flats with lines of washing waving in the wind, children playing in courtyards, ladies chatting in the streets and youth playing dice on street corners. The faded colours of the windswept landscape fade away as a young male on a bmx catches my eye. “Lady you look lost!” He smiles revealing a passion gap and two gold teeth. The vibrant culture of the Cape Flats community can be felt on every street corner and forms the heart beat of the Cape Flats.

Moments later I sit in a small office at the First Community Resource Centre waiting to meet the interrupters. The walls are covered with newspaper clippings with headlines that scream out at you. ‘Live Hard Die Young’ ’Gang War’ ‘Americans Wiped Out’ ‘Executed In Street’ ‘4 Year Old Shot Dead’. Hanover Park has one of the highest murder rates in the world and like most parts of the Cape Flats is plagued by gang violence. I look around waiting in anticipation. I hear voices coming from down the corridor. They enter the room.

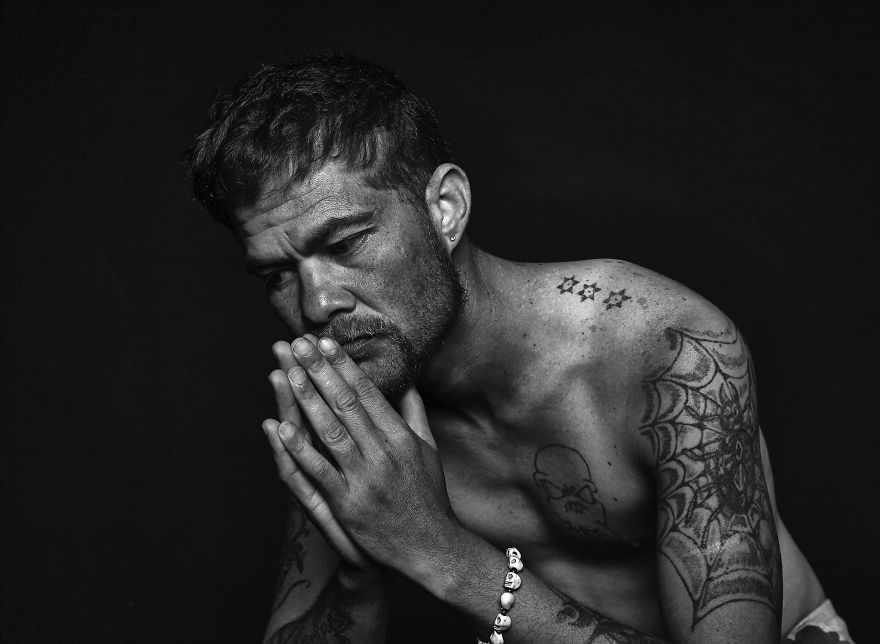

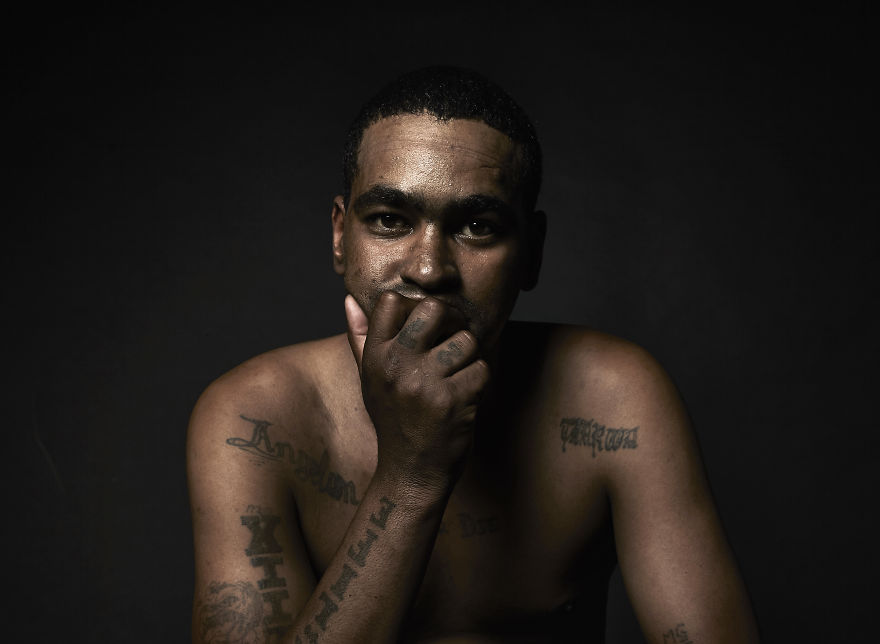

An eclectic mix of men of various ages and backgrounds and one female make up the team. On closer inspection I notice faded tattoos peeking out from under their shirts revealing their background as street gang members. Here and there you see the markings of The Number some 26, some 27 and some 28’s. If you look even closer you notice the scars from stab and gun shot wounds. These markings are like a book written across their bodies telling the story of their past.

Tall with a lean frame and sharp features, Khiyaam Frey, sits down opposite me. His brown eyes flicker as he looks to the ground and starts talking softly about the work he does. “This job you have to do with a lot of heart. People’s lives are at stake and if we are able to save a life we will. One of the most difficult things about changing your life is that you will always get those people who will hold the past against you. People judge you on your tattoos. They call you a skollie. But even skollies can change.”

I find it difficult to believe that this was once a violent man and active gang member. He now uses his knowledge of street gangs to work as a professional violence interrupter. He turns around to reveal large bold letters on his jacket ‘CEASEFIRE’. A word that carries a lot of meaning in a neighbourhood where the community is plagued by gang violence and innocent civilians and children are often caught in the crossfire.

It is estimated that someone is killed nearly every day in the Western Cape due to gang violence. This is the reality of the people that live in this community and many others across the Cape Flats. As I sit in the office overlooking Hanover Park, table mountain looming in the distance I think about this very different reality so far removed from the picture perfect Cape Town portrayed as a prime tourist destination. A mere 15 minutes drive from some of Cape Town’s most affluent neighbourhoods and palm lined beaches lies another city in the shadows where blood flows and violence is an everyday occurrence. Cape Town remains a deeply segregated city and The Cape Flats, home to over a million people has been accurately described as the “dumping ground of Apartheid.” When it comes to dealing with gang violence it feels like conventional approaches like policing and the prison system is failing this community, but maybe more importantly it is failing the young men who get pulled into gang life. We are alleviating the symptoms without addressing the cause and therefore, I don’t believe we have a gang problem as such but rather a social problem.

“In trying to understand gangs, we need to move past the sensational newspaper headlines and ask what can be done to help young people live meaningful, resilient lives in environments that characteristically favour the development of crime and violence.” Don Pinnock, criminologist and author of Gang Town.

Life on the Cape Flats produce young people who have so few life options due to a lack of opportunities, education and poverty, that for many, becoming a gang member is almost inevitable. Gang life provides a sense of brotherhood, identity, protection, pride and a place to belong.

Although it is easy to look away from the problems on the Cape Flats as most Capetonians aren't directly affected by it we simply can’t abandon another generation of youngsters to repeat the cycle of violence. Cape Town is ranked among the 10 most violent cities in the world and the statistics are frightening. A new and innovative approach in dealing with gang violence is needed and I have seen that a program like CeaseFire has the potential for great success.

Pastor Craven Engel, also known as The Eagle, is a visionary leader with a passion for his community. Engel runs the CeaseFire program in Hanover park. Engel has a great understanding of the problems plaguing his community and has found an unconventional but very effective way to treat violence in one of the most violent neighbourhoods in the world.

CeaseFire, a Cure Violence initiative, was founded by Gary Slutkin, MD, former head of the World Health Organisation’s Intervention Development Unit and Professor of Epidemiology and International Health at the University of Illinois/Chicago School of Public Health. The model is currently implemented in 8 countries spread over 5 continents. CeaseFire Hanover Park is partially funded by The City Of Cape Town.

Engel elaborates on the program : “CeaseFire is a public health programme that reduces violence particularly with regard to gang related shootings.It’s based on epidemiology. We treat violence like a disease. So we look at the transporter of violence and we quarantine him and then we look at who is most likely to get the disease and who he can contaminate. We alter their behaviour and offer them a better life. Unfortunately in a community like this violence has become normal and that is what we are trying to change. Violence is abnormal. So we look at environmental contamination and behavioural contamination. We do risk reduction and then we start rehabilitating the guys for a normal life. We do a 6 week in house program away from the beat at Camp Joy in Strandfontein. There we do anger management, communication, social integration, behaviour change, identity, skills development,speech therapy, anything to cool down the brain and stop the violence. Towards the end of the six weeks we also do job readiness to prepare the individual for a new credible life.”

The CeaseFire model was adapted to fit a South African context and was implemented in Hanover Park in 2013 after the baseline was done in 2012. The team consists of 6 interrupters: Khiyaam Frey, Suleiman Manuel, Abduraaghman Ruiters, Tasleem Johnson, Nealon Petersen, Patrick Hermanus and 5 outreach workers: Jeremy Davis, Wilfred McKay, Glenn Hans, Albert Matthews, Charmaine De Bruin, 2 administrators: Craven Engel, Raymond Swartz and 1 data coordinator: Urshwin Engel.

So what does it take to become an interrupter? Engel explains: “In order to be a CeaseFire worker you must have knowledge of street gangs and have been a gangster. If he was incarcerated it will add value to his cv. He must also have knowledge of prison gangs and prison activity and understand the number system. He must be able to understand Sabela (the language used by gangsters). If you can’t Sabela the gangsters will easily mislead you.Your street credibility is very important. Respect comes from both sides. If they don’t respect you, you won't be welcome with the high risk. Only a gangster can work with a gangster. But its very important that you can’t be an active gangster anymore. It’s a bit of a crazy cv. It’s all the stuff a normal job doesn’t want. You don’t apply to us we look for you.”

Being an interrupter is nothing like your average job. You are constantly bombarded with violence and the stress of dealing with high risk individuals. Its like constantly being in a war zone. Yet the team do their work with great passion and you will never catch them without a smile on their face despite everything they witness. The trauma sometimes takes its toll on the guys. Khiyaam Frey speaks about such an incident: “They shot him dead right in front of me. He did the last six shots while I was standing there. I asked pastor if I could take some time off after that. That kind of thing haunts you.”

These guys(gangsters) are living on consistent trauma, they never get healed. They just manage their trauma. It’s not a good space to be. Gang life is like that — constant trauma. Constantly looking over your shoulder, you are never safe. Your always on alert. The pressure of being a CeaseFire worker is similar.

Frey also proved how far he would go to do his job when he spent 35 days in Pollsmoor prison on false charges. He was responding to a shooting one Saturday evening. As he walked through the courtyard he became aware of some high risk individuals walking behind him carrying a weapon. The police pulled up and they ran away leaving the weapon 20 meters from Frey. The police arrested him despite the weapon not being on him. Although Frey knew the identity of the shooters he knew that violating the gang discipline of not snitching would cost him his credibility and compromise CeaseFires relationship and ability to work with the gang. He bit his tongue and spent 35 days in jail. “It was very hard. I never thought I would see the inside of a prison again after I changed my life.”

In order to successfully work with gangsters you need to respect the disciplines and codes of conduct that the gangs use. Although to an outsider gangs may appear chaotic and without order they are actually highly organised and they operate with great deal of discipline. Therefore CeaseFire doesn’t work with the law. There’s a discipline of not snitching and that is the only way that this program can survive, because once trust is broken on that level you will never be able to rebuild it.

One of the most remarkable ways CeaseFire reduces violence is by doing conflict mediations. When there is conflict in the area CeaseFire will request a mediation between rival gangs. So where before rival gangs would shoot at each other to resolve issues, they are now willing to meet face to face and talk about the issues. This in itself has never been accomplished before and without the help of CeaseFire it wouldn’t be possible. It has even progressed to a point where sometimes the gang will show a willingness to resolve conflict by requesting a mediation before things get out of hand.

Jeremy Davis, a serious man with a warm smile, explains how mediations have created progress: “We planted a seed and it’s growing. You don’t kill each other and then you talk, you talk first. That’s progress.”

Engel shares his insight on the matter: “The gangs never needed a law component to sort out their problems, they actually needed a mediator. We do different kinds of mediations depending on the situation. We do street mediations, phone mediations and also mediations to stop retaliations. When the violence is very high a group mediation will be done at a neutral venue outside of Hanover Park where both gangs feel safe. We will pick them up with our own transport and take them to a neutral ground where there are cameras and they know they won’t be ambushed or shot at.”

Because the team come from different gang and prison backgrounds they used to be rivals in the past. They used to shoot at each other and couldn’t move on each others grounds. Now these very same guys are working together as one team. When they get to this particular job they work as one team regardless of gang or religious backgrounds. And that is a great example of what is possible within the greater community.

CeaseFire makes use of the Shot Spotter technology to aid them in responding to shootings. Shot Spotter is a gun detection system that has been installed in the area. It picks up gun fire within two seconds and accurately pin points the location of the shooting. The app is installed on all the CeaseFire workers phones and so they are able to respond to shootings. It also helps them to predict where the next shooting will be and protects the workers so that they don’t walk straight into a shooting when they respond. Adding their knowledge of the gangs and shooters the team then overlays their knowledge with the data from the shot spotter to create valuable data to curb violence and prevent retaliations. It is the human aspect of the interrupters on the ground that make this the most effective way to reduce violence.

A few months after I first met the interrupters we attend the funeral of a leader figure I met a few hours before he was shot. It’s 07:00 on a Saturday morning and the street outside the deceased house is a beehive of activity. It’s raining and the air is tense. Every few minutes a police van drives past. A retaliation is likely. Abduraaghman ‘Abi’ Ruiters, a serious looking interrupter, is standing next to me. He can sense my sadness and gives me some insight into why this work is so important to him. “We are here to reduce the violence, and if we can reduce it, then there is a chance that it can stop. I put 20 years of bad into my community, now is my time to make it right.”

Frey appears from the shadows. They both knew him. I ask him how they deal with constantly facing death and violence. “Losing someone you know is a bit like a knife wound. It hurts like hell and takes a long time to heal but it doesn’t kill you and you just have to carry on.”

Tasleem ‘Tassie’ Johnson, the youngest interrupter and newest member of the team picks up the coffin, the man was his cousin. Last year Tassie decided to change his life and exit gang life. But it hasn’t been an easy journey for him. At the time of changing his life he lost 3 brother figures due to gang violence. A setback that would make most relapse and return to their old ways. The only way to deal with that kind of trauma is to retaliate and take revenge. But Tassie has remained strong and even his own gang salutes him for the way he was able to change his life. Tassie explains: “I changed my life for my kids. They didn’t ask to be here, I brought them into this world. I don’t want them to live the same life I did. I want something better for them.”

Religion plays an important role in the recovery of high risk individuals. They have great respect for religion. Therefore it is very important to have guys that come from a Muslim and Christian background on the team. One of the first things the gang will ask for when we open a mediation is “Can we open up with prayer?” The same guys that shoot and kill each other ask for this. So Engel understands how important faith and religion is for the high risk and the community. Religion and gangsterism might not sound like something that go hand in hand but the importance of religion probably stems from a very real awareness of their own mortality.

Jeremy Davis, Wilfred McKay, Glenn Hans, Albert Matthews, Urshwin Engel and Charmaine De Bruyn (the only woman on the team) work as outreach workers and spend their days between Camp Joy and the community centre in Hanover Park. Once a participant has expressed a desire to change their life they will be assigned an outreach worker. Dealing with the youth at risk comes naturally to them. McKay, who you will always find smiling, becomes very serious when he tells me about a participant that he worked with for 8 years who was shot dead. “You get close to people and you get used to them you know. Its like losing your own son.”

A few months after I first met the interrupters I’m sitting in a dusty courtyard amongst flats in an area known as The Valley of The Plenty (Mongrel territory) with Nealon Petersen, a veteran amongst his colleagues and the oldest member of the infamous Mongrels gang. A group of youth walk past. Nealon looks at the youth and shakes his head in dismay. He express his fear and concern for the youth being pulled into gang life. “I’m worried for these youngsters. I’ve seen where gang life takes you and it doesn’t look good. You end up in prison, a wheelchair or a coffin.”

I ask Nealon what being an interrupter means to him. “Baby girl, I will do this work till the day I take my very last breath. CeaseFire for life.” He smiles revealing a row of gold teeth.

This program saves lives. In 2016 CeaseFire reduced gang violence by 43%. On the ground it means that a lot of lives were saved. Almost half of the people that should have died didn’t.

Every gangster deserves the opportunity for a better life, yet the justice system doesn’t process high risk individuals. It is an extremely difficult job that no one wants to deal with it. But pastor Craven Engel and the CeaseFire team are not afraid to get involved and do the work no one wants to, to help this community and bring about real change.

CeaseFire is proof that you can change the ending and that you can use your past to create a better future. Change is possible.

More info: youtube.com

This post may include affiliate links.

The Elder

You can’t blame the youngsters for joining gangs. Life in the Cape Flats produce young people who have so few life options that, for many, becoming a gang member is almost inevitable. They say if you can’t beat them, join them. How will you become something in this life if your family doesn’t have money for you to go to college or to start a business? Then you become a gangster. It’s the only way you can move forward in life. The gang gives you money and status. Then they give you a gun and you shoot your way through life. Now you can buy a nice pair of tekkies, a lekker tracksuit, a golden tandjie or a cellphone. That is the thing that everybody longs for. To have your own money in your pocket. To be a somebody. Its human nature to want to belong somewhere and feel safe and gangs provide that along with a sense of brotherhood and protection.

Nealon Petersen

Redemption

The thing in life is everybody wants to belong somewhere. Everybody wants to be loved. Some people find this love and sense of belonging in their family or with their friends. Some find it in a gang.

In The Land Of The Free

My name is Patrick Hermanus and I come from the States, not the United States of America. There are a lot of Americans here but they are nothing like the ones you see on TV. I remember the day I changed my life very clearly. I was driving around with a fellow American, Gavin Myburgh and his girlfriend. We stopped at Access Park to buy a cool drink. As he got out the car he put on some gospel music and said something very odd “If I have to die today I know that I have made things right with God”. I sat in the car listening to the music thinking about what he said. When they came back they were barely seated in the car when they opened fire on us from both sides. I lay down flat in the back of the car until they ceased fire. I looked around the car which was riddled with bullets holes, the gospel music still playing in the background. A few minutes later Gavin died. That was the day I changed my life. That was the example of what my future looked like. I had a high rank with the 26’s. I was an officer and so it was my job to give orders, but God came to save me, and now there are no more orders to give.

Patrick Hermanus

At Liberty

There is such a strong sense of Us and Them when it comes to gangs and the community. Gang identity is so strong and obvious for both insiders and outsiders. I spent twenty years with the Americans. When you have been involved with gang activities for so long it becomes such a big part of your identity. It’s all you have ever known and been. Changing is a daily battle. Now you have to find a new identity and step into that. That can be hard you know. But the good in your life and your sense of purpose makes it easier. My life serves as an example for others that change is possible and that keeps me going. We provide hope for the hopeless.

Wilfred McKay

In The Valley Of Plenty

I was born in Hanover Park and I have lived in The Plenty (that’s short for In The Valley Of Plenty) all my life. At age sixteen I joined the Mongrels. There was a lot of sadness in my life, before I changed. My own gang did a lot of things that hurt me. They shot my cousin who was also a Mongrel. His own gang shot him, just like that. That’s how it goes. Today your brother is your friend and tomorrow he will turn against you. I changed my life for my family and kids. They didn’t ask to be here, I brought them into this world. I don’t want them to live the same life I did. I don’t want my son to think, hey I want to be a gangster like my daddy. I want something better for them.

Tasleem Johnson

A New Kind Of Brotherhood

From an early age kids identify with gang identity. If you ask a kid where he lives he’ll tell you there by the Americans or the Hard Livings, and therefore he won’t be friends with a kid from the Ghetto area. It starts of very innocent, kids play fighting with sticks and stones and as they get older sticks and stones progress to knives and guns and then you really have a problem. This brotherhood becomes your life, but even your own brothers forget about you when you go to prison. You can be a leader in prison, you can have everything you want, but the one thing you will never have is your freedom.

Suleiman Manuel

Stars And Stripes

In a place like Hanover Park violence is considered normal. Before it was an eye for an eye but now we are taking a new approach. We planted a seed and it’s growing. You don’t kill each other and then you talk, you talk first. That’s progress. The gangs need a mediator to resolve conflict and that’s what we provide. It has progressed to a point where the gang will call us when there is conflict and ask for help. You have to know how to talk to these guys and how to approach them and work with them. Only a gangster can work with a gangster.

- Jeremy Davis

The Thinker

Things changed when I got out of prison after a nine year sentence. Everything was different. I was different. Nine years in prison is a long time. You can’t expect things to stay the same. Most of my friends were shot dead. I lost a lot of friends back then. One night I looked in the mirror and asked myself: Is this really who I want to be? I decided to change my life. One of the most difficult things about changing your life is that you will always get those people who will hold the past against you. People judge you based on your tattoos. They call you a skollie. But even skollies can change.

Khiyaam Frey

Little Devel

On the 16th of June 2014 I was shot in the head and the bullet came out the roof of my mouth. It’s a miracle that I’m still alive. I should have been paralysed. My own friends shot me through the head. Gang life is like that. Even your own brothers turn against you. I knew I had to change my life. I got the nickname Little Devel (Devil) when I was in prison at Victor Verster and so I got it tattooed on my neck. This caused some problems for me when I changed my life and I got a job at the NG church. When the pastor saw my tattoo he asked me not to come back to work the next day. Changing your life is very difficult, because people in the community still judge you. It takes a long time for them to believe that a once violent person has changed. But change is possible and you just have to school yourself in this new way of life.

Samuel Gerwel

How Can A Loser Become A Winner

There is no future in gangsterism. It doesn’t pay to be a gangster. You just keep losing in life when you are with a gang. You either go to prison or the grave or you end up in a wheelchair. I always wanted to be a winner in life. The day I changed my life I became a winner. How can a loser become a winner? By changing the ending against all odds. I can now use my past to change the future for myself and my community.

Nealon Petersen

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime