Paintings can be far more complicated than they appear at first glance. The stories told by works of art are the stuff of novels. Here are a few of the stories behind famous masterpieces.

This post may include affiliate links.

Christina's World, Andrew Wyeth, 1948

The faceless woman lying on the ground is Anna Christina Olson, the neighbor of Pennsylvania artist Andrew Wyeth. While the painting has all the hallmarks of a pastoral, it isn’t meant to be a romantic setting. Olson suffered from a muscle-wasting disorder, and Wyeth had seen her on many occasions dragging herself across the family homestead.

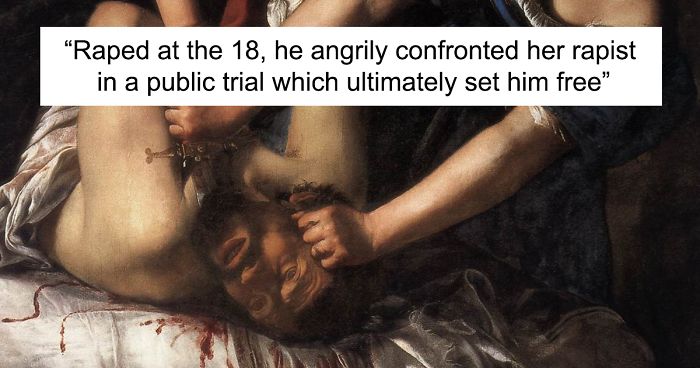

Judith Slaying Holofernes, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1610

Raped at the 18, Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi angrily confronted her rapist in a public trial which ultimately set him free. She channeled her ensuing rage into her work, notably “Judith Slaying Holofernes,” which depicts determined Old Testament heroine Judith severing the head of the drunken Babylonian general.

This is one of the paintings "Judith Slaying Holofernes" she painted. One in 1611-1612 and the other in 1612-1621.

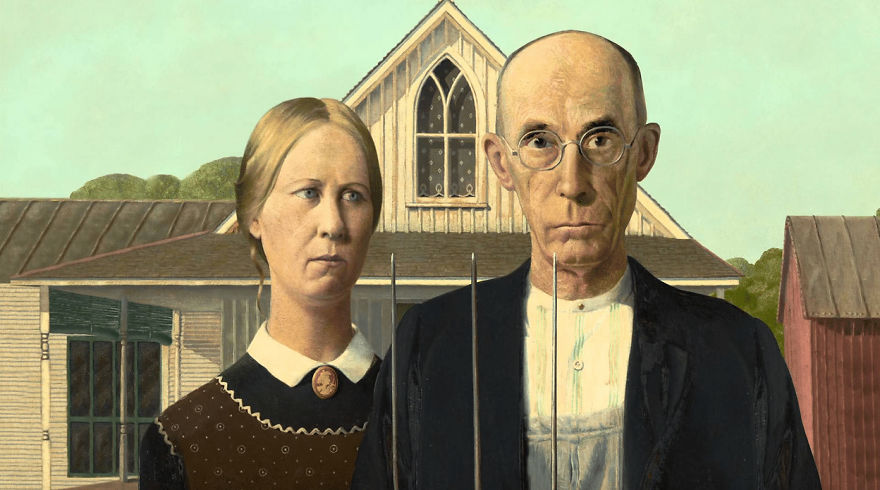

American Gothic, Grant Wood, 1930

Grant Wood was a national icon and leading exponent of regionalism. His most famous painting “American Gothic” depicts a Depression-era farmer and his weathered wife. Grant intended the couple to represent father and daughter; in reality, they were neither. The man holding the pitchfork was Wood’s dentist, Byron McKeeby, flanked by the artist’s sister, Nan Wood Graham.

So... they were meant to look like father and daughter, looked like husband and wife, but are neither? Cool.

Girl With A Pearl Earring, Johannes Vermeer, 1665

Little is know about the young woman depicted in Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring.” It has been suggested that the girl was either Vermeer’s daughter or his mistress. While either may be the case, the image wasn’t intended to represent an actual person. The turban worn by the sitter indicates that the piece was intended as a “tronie”—an idealized image cloaked in exotic clothing.

Ophelia, Sir John Everett Millais, 1851-52

John Everett Millais painted directly from life whenever possible. Therefore, much of the foliage found in “Ophelia” can be found in Shakespeare's “Hamlet.” However, Millais didn’t subject his 19-year-old model, Elizabeth Siddall, to the elements; she reportedly posed for the artist in a bathtub full of water in his London studio.

The water was heated by candles. When the candles went out the artist continued painting her and she almost died from pneumonia.

Portrait Of Madame X, John Singer Sargent, 1883–84

John Singer Sargent hoped this piece would make his career. However, the painting of Virginie Avegno Gautreau, the American wife of a French banker, outraged critics when it was first exhibited at the Paris Salon 1884. While overt sexuality was expected when the subject was a mythological heroine and tolerable when it was a prostitute moonlighting as an artist’s model, it was downright offensive when it applied to a woman of upper-crust Parisian society.

Mona Lisa, Leonardo Da Vinci, 1503

Traditionally, the Mona Lisa has been identified as Italian noblewoman Lisa Del Giocondo. Countless hypotheses have been put forth as to the explanations for her enigmatic smile. Extensive multi-spectral imaging conducted by Lumiere Technology in 2006 uncovered years of varnish revealed that her smile was originally broader than it appears today.

The Two Fridas, Frida Kahlo, 1939

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s work is infused with a deeply personal iconography and references a life of physical and emotional anguish. “The Two Fridas” portrays the artist before and after her painful separation from Rivera; on the left as a bride with an eviscerated heart, and on the right dressed in the traditional Mexican costume, she favored during happier times with Rivera.

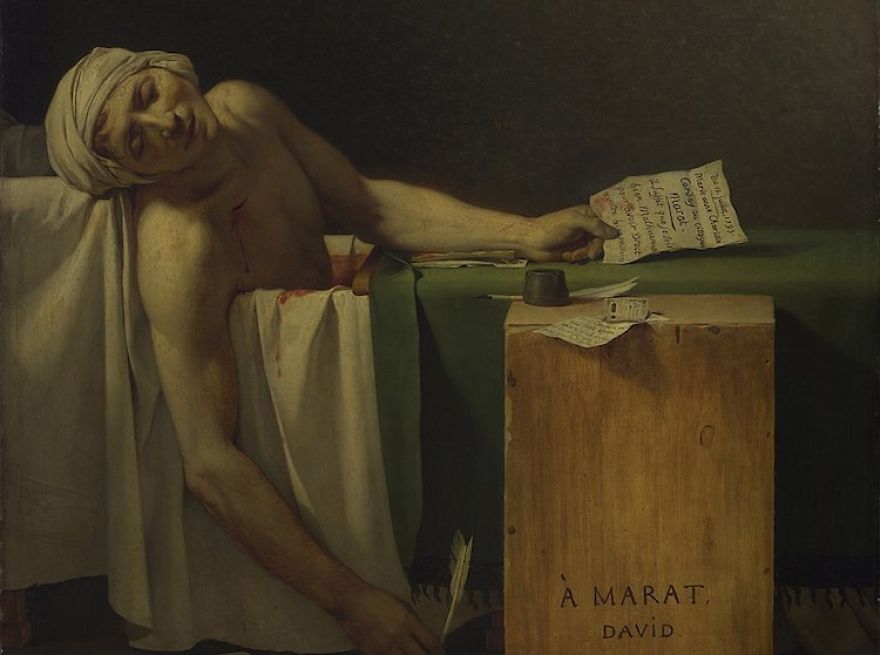

Death Of Marat, Jacques-Louis David, 1793

The pallid figure bleeding out in Jaques-Louis David’s masterpiece is Jean-Paul Marat, the French revolutionary stabbed to death by a political adversary while in the bath. David gravitated toward radical politics, aligning himself with the Jacobin ideologies of Marat and Maximilien Robespierre. In post-revolutionary France, he rose to the position of court painter under Napoleon Bonaparte.

I don't feel sorry for marat. I feel sorry for Charlotte Corday... 4 days later they executed her with the guillotine...

Washington Crossing The Delaware, Emanuel Leutze, 1851

Not only was the iconic “Washington Crossing the Delaware” painted almost 75 years after the Revolutionary War, but it was also painted by a German artist—Emanuel Leutze—in Düsseldorf. Leutze had spent time in the U.S. and painted the scene with the hope that it would inspire European revolutionaries.

Andolfini Portrait, Jan Van Eyck, 1434

The couple is thought to be Giovanni di Nicolao di Arnolfini, and his wife, Costanza Trenta, wealthy Italians living in Bruges, West Flanders. The unusual composition begs several questions. Does the painting celebrate the couple’s wedding or some other event? Was the bride pregnant or simply dressed in the latest fashion? And what are the mysterious figures depicted in the convex mirror? The unorthodox placement of van Eyck’s signature directly above it suggests one of the men may be the artist himself.

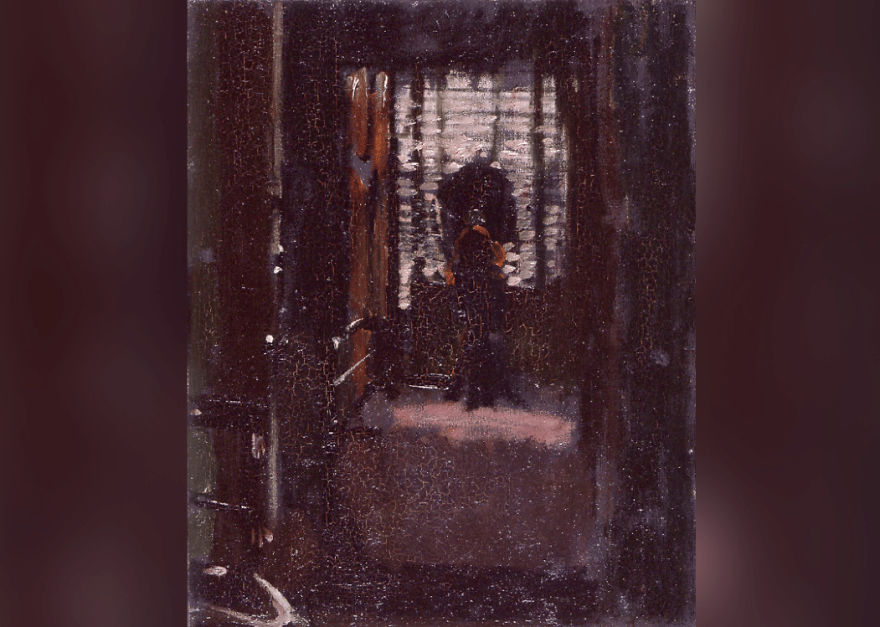

Jack The Ripper's Bedroom, Walter Sickert, 1908

Walter Sickert, noted for his moody portraits and dimly lit domestic interiors, may have harbored a secret darker than his paintings. It has been argued that disconcerting works such as “Jack the Ripper’s Bedroom” and “The Camden Town Murder” may reflect some connection between the artist and the grisly Whitechapel butcher—either as an accomplice or the murderer himself.

The writer Patricia Cornwell is convinced that Sickert is indeed the Ripper himself, having written a book and fronted a tv show explaining her theory. But there is diffident evidence to rule him out completely.

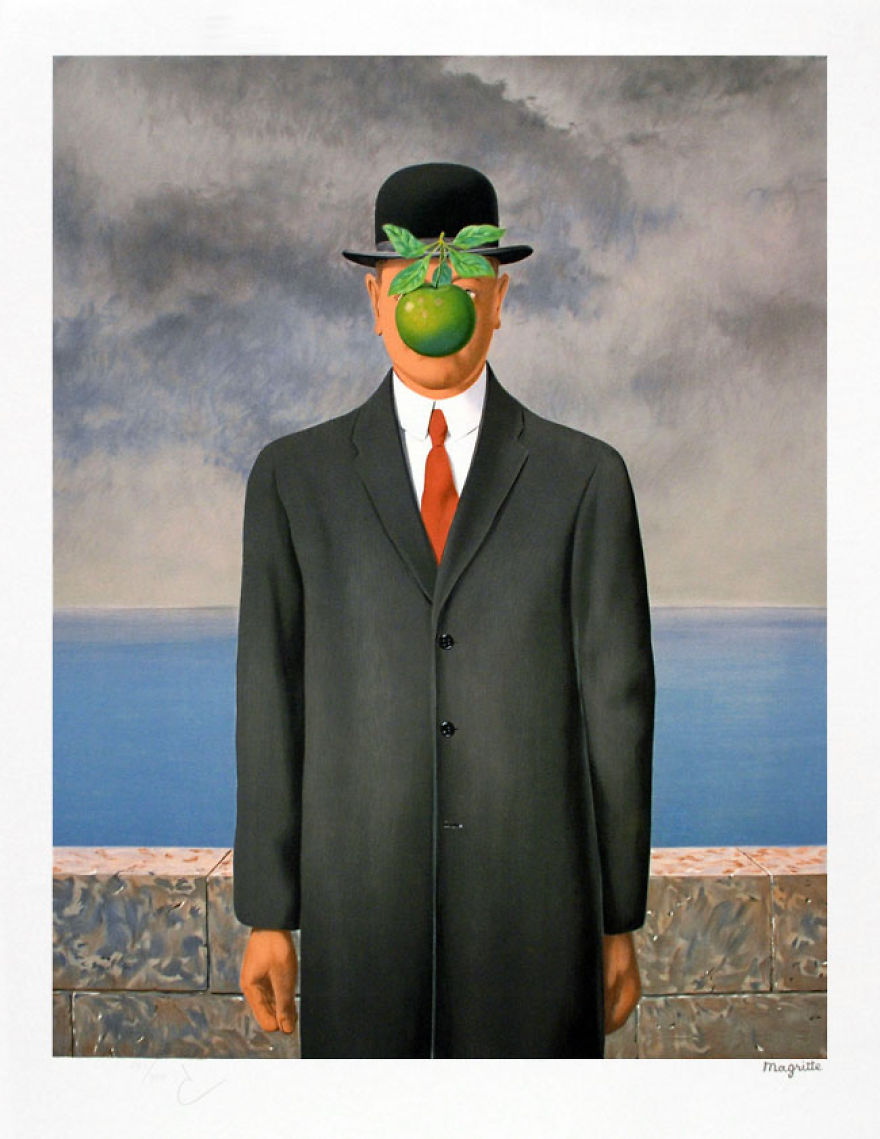

The Son Of Man, René Magritte, 1946

The works of the Belgian painter René Magritte are frequently head-scratchers, and “The Son of Man”—a self-portrait of the artist with his face obscured by a giant apple—is no exception. The apple was one of the artist’s favorite motifs, but its meaning is uncertain. The title chosen by Magritte is perhaps more illuminating, referencing Jesus Christ. Some critics have called the piece a surrealist interpretation of the transfiguration of Jesus.

I always thought that it was referencing the fruit (usually thought of as apples) Adam and Eve ate in the garden of Eden, making them unholy and 'a son of man' instead of god

Cyclops, Odilon Redon, 1914

It is a tale straight out of Greek mythology. Polyphemus, the giant that is sporting the solitary eyeball, peers over a rocky outcropping at the object of his desire—the nymph Galatea. Derived from Homer’s “Odyssey,” the tale was a popular trope among French symbolists, including Redon’s contemporary, poet and painter Gustave Moreau.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime