“Money Can Buy Women?”: Japan Cancels Incentive For Women To Marry Rural Men Following Backlash

The government of Japan has been forced to scrap a controversial proposal offering cash incentives for urban women to marry rural men after the initiative was met with public backlash.

The plan involved giving single women from Tokyo up to 600,000 yen (around $4,260) to move to rural areas to address the shrinking female population in the countryside due to women moving to the cities for education and work.

- Japan cancels a cash incentive plan for urban women to wed rural men after public backlash.

- The plan offered up to 600,000 yen to women to move to rural areas to address female population decline.

- A survey indicated lack of partner opportunities and financial resources as reasons for low birth rates.

- Japan’s birth rate hit a record low of 1.2 in 2023, with Tokyo dipping below 1.0 for the first time.

The program covered travel costs for matchmaking events, in an attempt to address Japan’s record-breaking birth rates which, in 2023, reached the lowest in the country since 1899 according to data from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

“We will carefully listen to the voices of people who are struggling due to income gaps between men and women, gender bias, and other reasons, and take measures,” Hanako Jimi, Japan’s Regional Revitalization Minister, said in a statement.

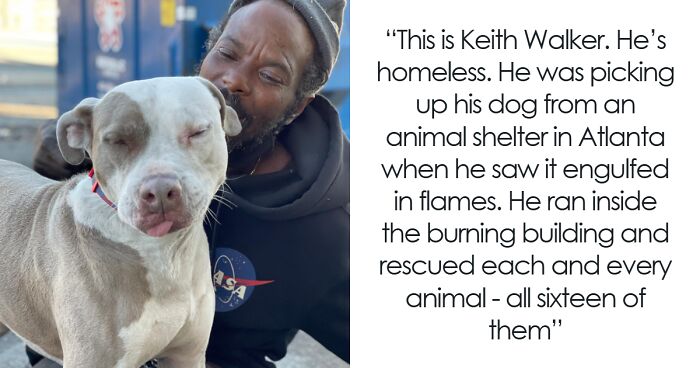

Japan was forced to reevaluate their program that offered women more than $4,000 to move to rural areas and marry after public backlash

Image credits: cottonbro studio

The nature of the financial incentive offered to Japanese women in exchange for them moving into rural areas to marry had some Japanese netizens labeling the program as “sexist” and “tone-deaf.”

“Do they still not get it? This is something people who see women as valuable only if they give birth would come up with,” one user wrote on X.

“Do they think money can buy women?” Asked another. “They are trying to ‘utilize’ women.”

Criticism also came from within the government of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

“If we try to motivate people to move to regional areas by using marriage, and leave the root cause of the problem unattended, it won’t be the right way to do it,” stated Wakako Yara, adviser to Kishida.

However, even if the method wasn’t well received this time around, inactivity is not an option for the Asian country anymore, as it faces an existential crisis with a rapidly aging population that’s not going to be able to be supported by a younger generation in the future.

An online survey of around 4,000 men and women aged between 20 to 40 years old tried to find the root cause behind the declining birth rates

Image credits: Artem Podrez

The research, part of Japan’s Cabinet Office’s annual report, cited a lack of opportunities to meet a partner, a lack of financial resources, and an inability to get along with the opposite sex as the main reasons given by respondents as to why they were unable to get into a relationship.

In 2018, the country set a goal of raising its fertility rate to 1.8 but the trend is making that dream very difficult to achieve.

As of 2023, Japan’s birth rate hit a record low of 1.2, signaling a year-by-year decrease of 0.06 points. While the drop was present in all 47 prefectures, Tokyo was the most affected, dipping below 1.0 for the first time to 0.99.

For reference, the fertility rate is the average number of children born per woman up to age 50.

Image credits: cottonbro studio

According to the United Nations, a high fertility rate is one of 5 kids per woman. Conversely, replacement-level fertility is achieved at 2.1, and is the bare minimum for a country’s population to replace itself on a generation-by-generation basis not accounting for migration.

Very low fertility is anything below 1.3 children per woman, which means that numbers such as Tokyo’s are extreme, but still somewhat far above those of its neighboring country South Korea, which has the lowest fertility rate in the world, at 0.78.

Higher cost of living and uncertainty about the future have led the youth to reevaluate their priorities, opting for a more austere lifestyle

Image credits: cottonbro studio

According to Kenichi Ohmae, a well-known Japanese scholar who focuses on socioeconomic issues, the problem goes beyond birth-rates and is a symptom of a deeper problem affecting the youth of the country.

In his 2018 book How to Ignite a Low-Desire Society?, the author describes how long periods of low economic growth force the younger generation to reevaluate their goals.

“Low-desire does not mean an absence of it, but a shift towards a more passive existence,” he states, explaining that the inability to financially sustain a more expensive lifestyle or a family leads to people finding happiness in what they can actually get.

Ohmae explains that this “complacency” acts as a defense mechanism and ultimately results in young adults being increasingly hesitant to marry, have children, or even engage in romantic relationships.

On the financial front, it translates into a reluctance to take on debt and a more austere lifestyle in the face of economic uncertainty.

Netizens took to social media to decipher the reasons behind the phenomenon, with many pointing towards urbanization as the culprit

Image credits: Tùng Sơn

“It really does seem like a high cost of living city thing. I swear Seoul and San Francisco have more dogs than kids,” wrote one user on Reddit.

“Housing in the parts of the city where young people want to live are not suited for children,” explained another, pointing out how hostile certain cities can be towards infants.

“Urbanization is cratering birthrates all across the world,” one replied. “The countryside is always going to be a much better place to raise children than a major city.”

“Companies in Japan have a nasty habit of moving young people to major cities like Tokyo or Osaka,” a local explains. “These cities are hellishly expensive. Food is expensive, rent is expensive, everything is expensive.”

The government predicts that the country’s population will decline by about 30% by 2070, with 4 out of 10 citizens being 65 years or older, putting a significant strain on the working population.

Poll Question

Thanks! Check out the results:

Just like EVERY OTHER COUNTRY with declining birth rates, governments absolutely refuse to address the two root causes: LOW WAGES and OVERPRICED HOUSING. If people can't afford to feed and house themselves, then WHY would they get married and have kids? The only positive you can take out of Japan's response is they're not trying to legalize rape and ban abortion like rightwingnuts in other countries are trying to do (e.g. yankland).

Japan also has some seriously deep rooted issues all their own to add to the wages/housing problem. Their work culture and ideas of gender roles are really toxic and absolutely make the idea of family and children incredibly unappealing. You can get a whiff of that in the proposal, their entire idea for "how can we make rural marriage attractive" isn't even to bribe women, it's to defray the cost they would incur for a marriage to happen. Basically saying "well, what if we didn't make you pay out of pocket for the privilege of being treated like a baby producing machine being assigned to marry for production reasons"

Load More Replies...IMHO, 1.2 should've been our goal population "growth" 20 years ago. More people cost more money (not to mention all the other resources), so the argument that we need more children to support previous generations is ludicrous. How is a child(ren) of a poor family going to be more capable of supporting themselves AND their parents??

Several decades ago, the problem was that women returning to the workforce from having children were overwhelmingly going into "non-regular employment" (i.e., less than full-time work). This is still the case (>50%), primarily because Japanese cultural norms require ridiculous hours for "regular" employment -- which mean that you essentially can't have **any** childcare responsibilities at the same time. Getting an increase in the fertility rate would require taking on this norm (i.e., making it possible for women with kids to have full-time employment), along with overall assumptions about the role of women.

Just like EVERY OTHER COUNTRY with declining birth rates, governments absolutely refuse to address the two root causes: LOW WAGES and OVERPRICED HOUSING. If people can't afford to feed and house themselves, then WHY would they get married and have kids? The only positive you can take out of Japan's response is they're not trying to legalize rape and ban abortion like rightwingnuts in other countries are trying to do (e.g. yankland).

Japan also has some seriously deep rooted issues all their own to add to the wages/housing problem. Their work culture and ideas of gender roles are really toxic and absolutely make the idea of family and children incredibly unappealing. You can get a whiff of that in the proposal, their entire idea for "how can we make rural marriage attractive" isn't even to bribe women, it's to defray the cost they would incur for a marriage to happen. Basically saying "well, what if we didn't make you pay out of pocket for the privilege of being treated like a baby producing machine being assigned to marry for production reasons"

Load More Replies...IMHO, 1.2 should've been our goal population "growth" 20 years ago. More people cost more money (not to mention all the other resources), so the argument that we need more children to support previous generations is ludicrous. How is a child(ren) of a poor family going to be more capable of supporting themselves AND their parents??

Several decades ago, the problem was that women returning to the workforce from having children were overwhelmingly going into "non-regular employment" (i.e., less than full-time work). This is still the case (>50%), primarily because Japanese cultural norms require ridiculous hours for "regular" employment -- which mean that you essentially can't have **any** childcare responsibilities at the same time. Getting an increase in the fertility rate would require taking on this norm (i.e., making it possible for women with kids to have full-time employment), along with overall assumptions about the role of women.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

27

12