Twitter Account That Offers “A Beautiful Education” Explains Why Some Cities Feel More Alive Than Others

Jennifer Bradley, founding director of the Center for Urban Innovation at the Aspen Institute and co-author, with Bruce Katz, of The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros Are Fixing Our Broken Politics and Fragile Economy, thinks that in too many cities “public” has become synonymous with shoddy, dirty, dangerous and second-rate.

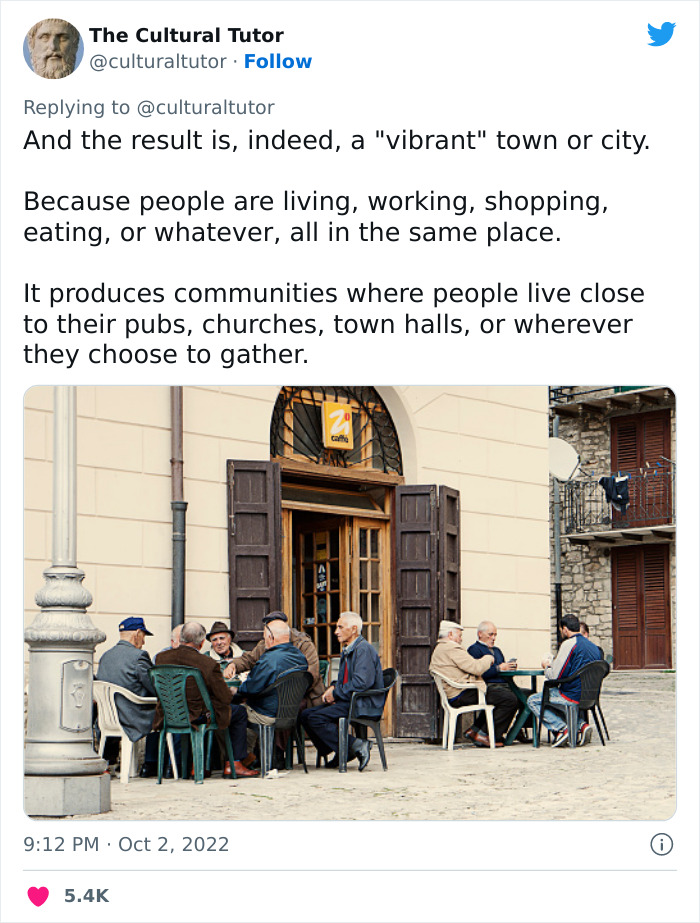

“The low quality of, and low expectations for, public services and spaces might not seem like an existential threat to cities, but when people stop believing in the value of public provisions, stop using them and paying for them, cities lose their core function: to be places of opportunity, places of mixing of people, ideas, cultures and habits, which produces more innovation and more mixing—a virtuous cycle,” Bradley explained to Politico.

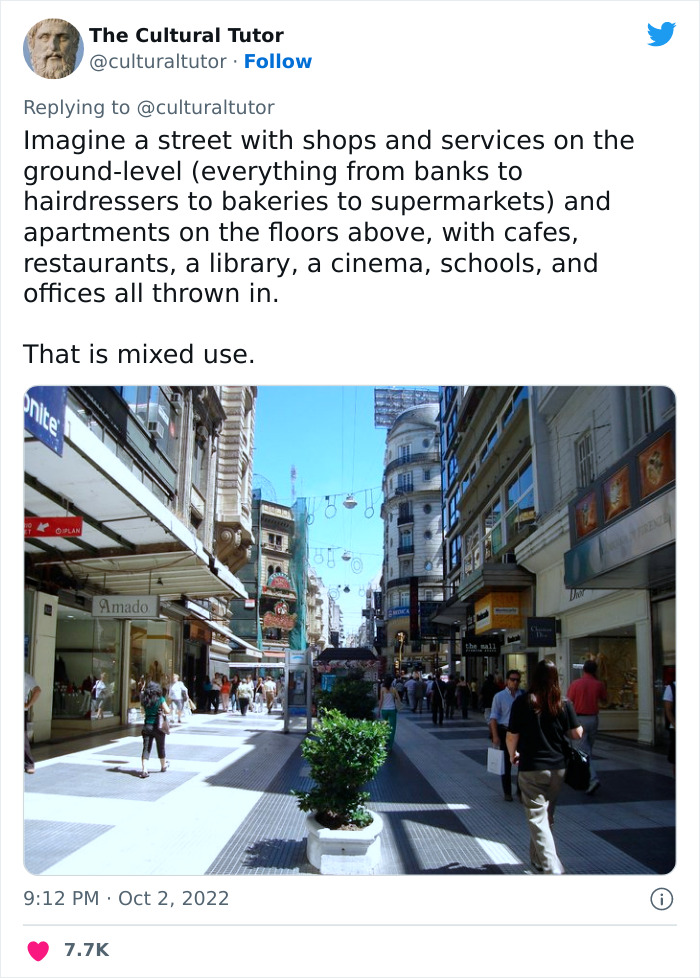

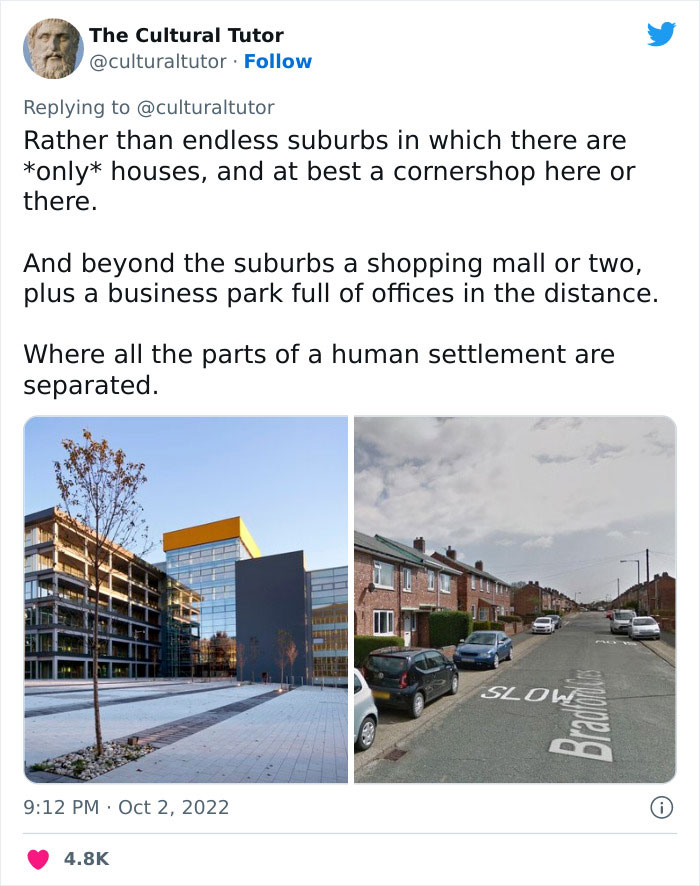

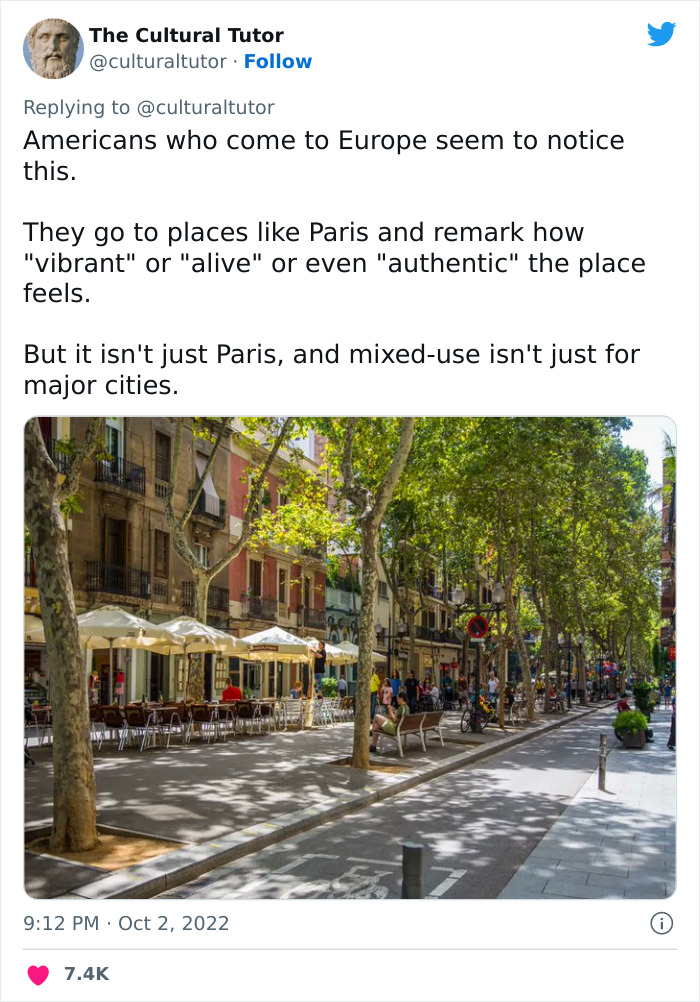

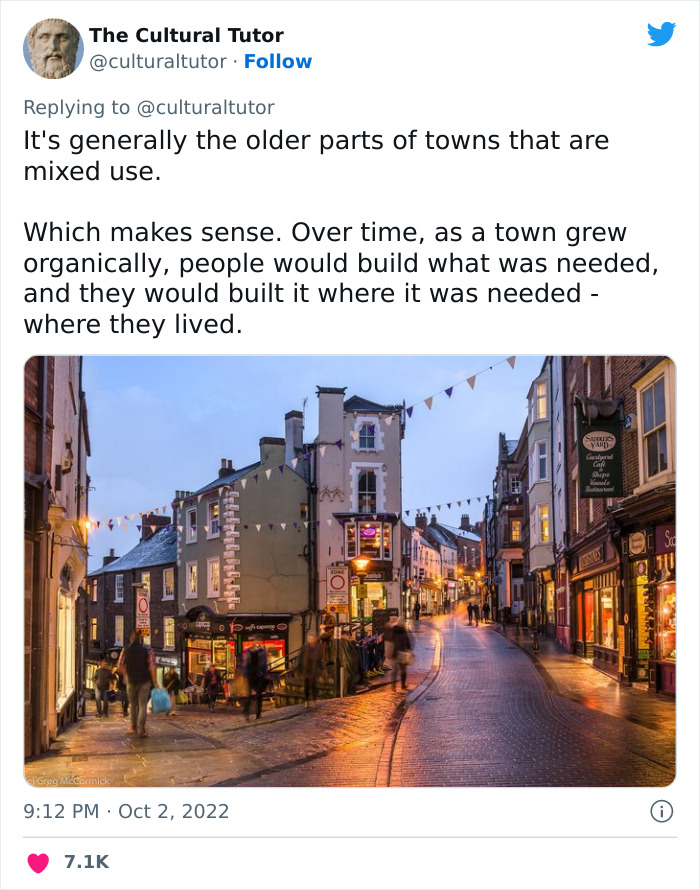

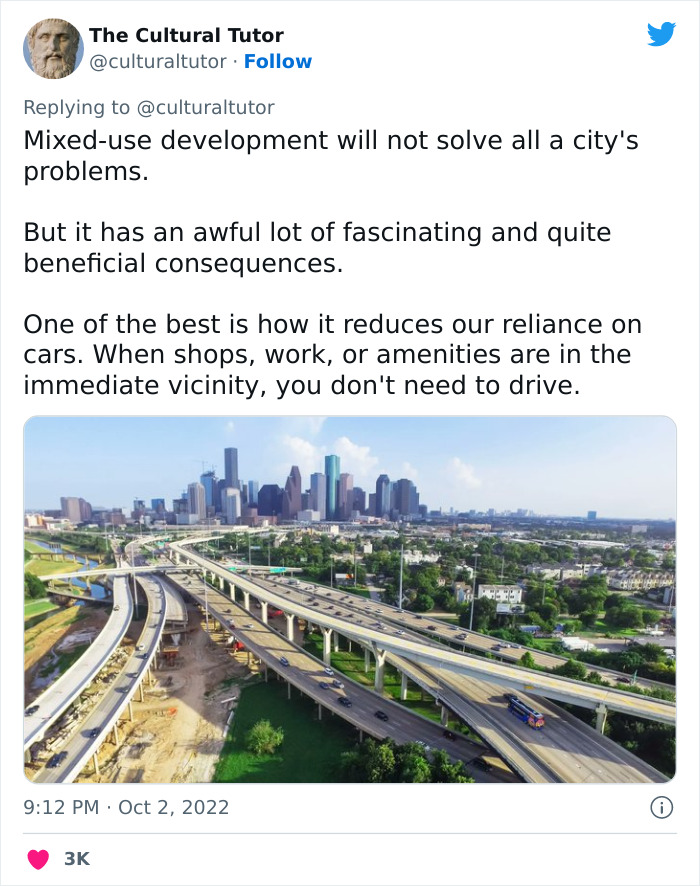

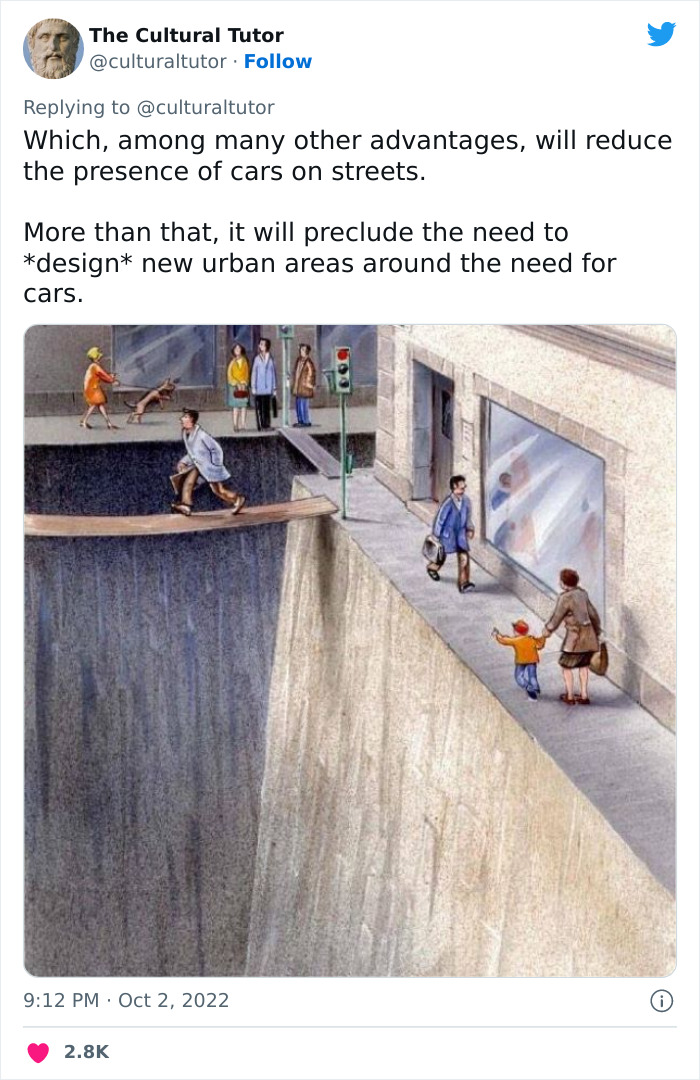

So how can urban planners facilitate the development of a more colorful, vibrant settlement instead of a lifeless one? Well, one way is to adopt a so-called mixed-use approach. And there’s a recent Twitter thread by the account ‘The Cultural Tutor’ that explains this concept beautifully.

More info: culturaltutor.com | Twitter

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

Image credits: culturaltutor

As Alan Rowley pointed out in his article ‘Mixed-use Development: Ambiguous concept, simplistic analysis and wishful thinking?‘, mixed use occurs in different settings. Putting aside the town- or city-wide level (since all of them at this scale are essentially mixed, although perhaps insufficiently), the other four settings are: (1) within districts or neighborhoods; (2) within the street and other public spaces; (3) within building or street blocks; and (4) within individual buildings.

Additionally, Rowley explained that there are virtually four types of location where mixed-use settings are found or may be promoted: (1) city or town centers comprising the commercial and civic core of towns and cities; (2) inner-city areas and on brownland sites comprising derelict, vacant or built-up land needing regeneration; (3) suburban or edge-of-town locations; and (4) greenfield locations where planning policy permits.

Finally, according to him, there are three basic approaches to maintaining or promoting mixed-use settings: (1) conservation of established mixed-use settings; (2) gradual revitalization and incremental restructuring of existing parts of towns, including infill development and reuse, conversion and refurbishment; and (3) comprehensive development or redevelopment of larger areas and sites.

Jane Jacobs is a trenchant and frequently quoted advocate of the virtues of mixed-use development. She defined four indispensable conditions for generating exuberant diversity in a city’s streets and districts, asserting that all four were necessary to create street diversity and that if any one was missing, the potential vitality would be undermined:

- The district, and indeed as many of its internal parts as possible, must serve more than one primary function; preferably more than two. These must ensure the presence of people who go outdoors on different schedules and are in the place for different purposes, but who are able to use many facilities in common;

- Most blocks must be short; that is, streets and opportunities to turn corners must be frequent;

- The district must mingle buildings that vary in age and condition, including a good proportion of old ones so that they vary in the economic yield that they produce. This mingling must be fairly close grained;

- There must be a sufficiently dense concentration of people, for whatever purposes they may be there. This includes dense concentration in the case of people who are there because of residence.

However, Jacobs’s analysis and conclusions were rooted in observations of city life and economics in late 1950s America and since then much has changed. It is now even harder to maintain, let alone reproduce the kind of diversity, vitality and general sense of community that she so admired.

Some people support this approach

Image credits: miketaiyou1

Image credits: asdkjfalksjdfla

Image credits: jmbnewman

Image credits: nurrrwhale382

Image credits: caroIene

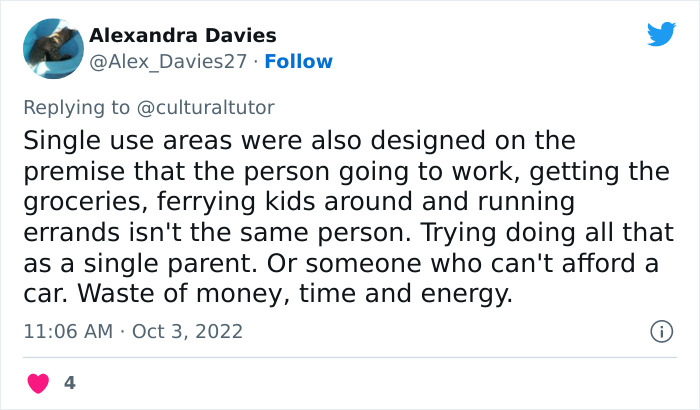

Image credits: Alex_Davies27

Image credits: Alex_Davies27

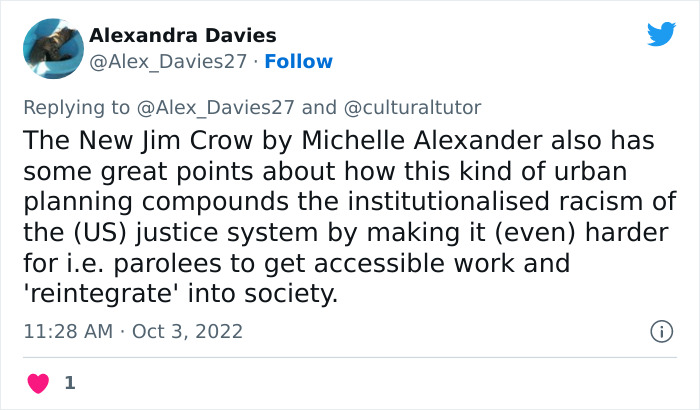

Image credits: caisson68

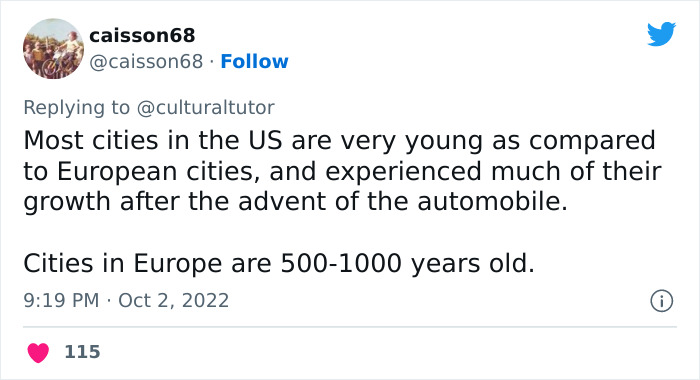

Image credits: BrandtAWitt

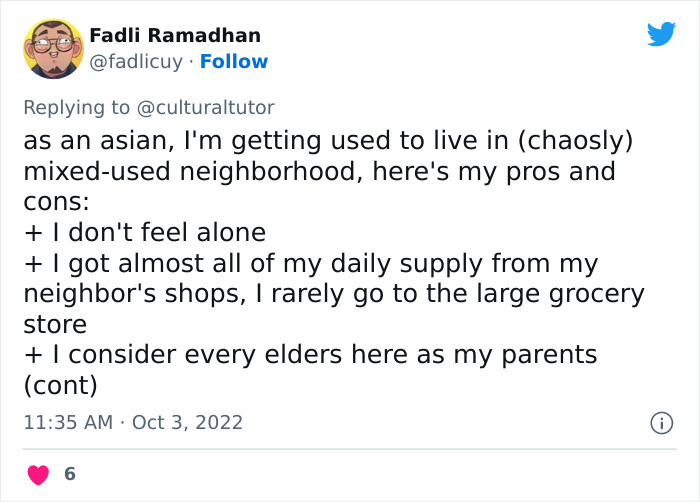

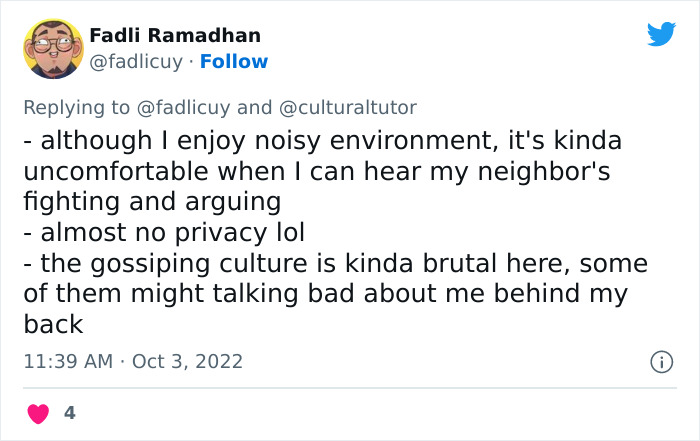

Image credits: fadlicuy

Image credits: jfadlicuy

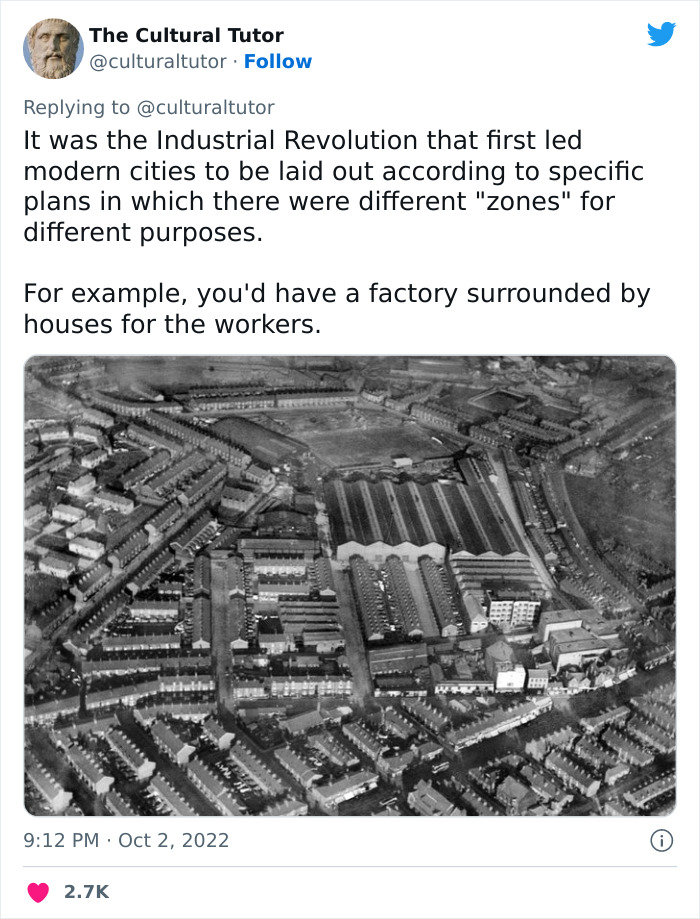

Rowley said that, “pre-industrial cities are, in many ways, models of conservation and material frugality, demanding far less of the environment in terms of land and energy consumption than modern cities.”

“But they were built to fit a very different set of requirements even though they have proved remarkably resilient in the face of changing needs and values. Planners cannot hope simply to turn the clock back, and expect to retain widespread popular support and market appeal for new developments which emulate the kinds of conditions and densities involved.”

Planners tend to underestimate the significance of the development process’s needs and how values and visions translate into bricks and mortar. “The processes of city building are initiated and carried out by three main sets of interests: (1) profit-seeking private developers and investors; (2) public authorities; and (3) voluntary organizations, groups and individuals,” Rowley explained. The motives of these parties are varied and frequently contradictory, calling for balance and compromise.

“Mixed-use development can promote urban quality, making settlements more attractive, liveable, memorable and sustainable; but we need to be clear about the kind of settings and situations in which such objectives are best realized. Equally, mixed-use development is not an automatic panacea and there are obstacles to promoting and maintaining more integrated environments.”

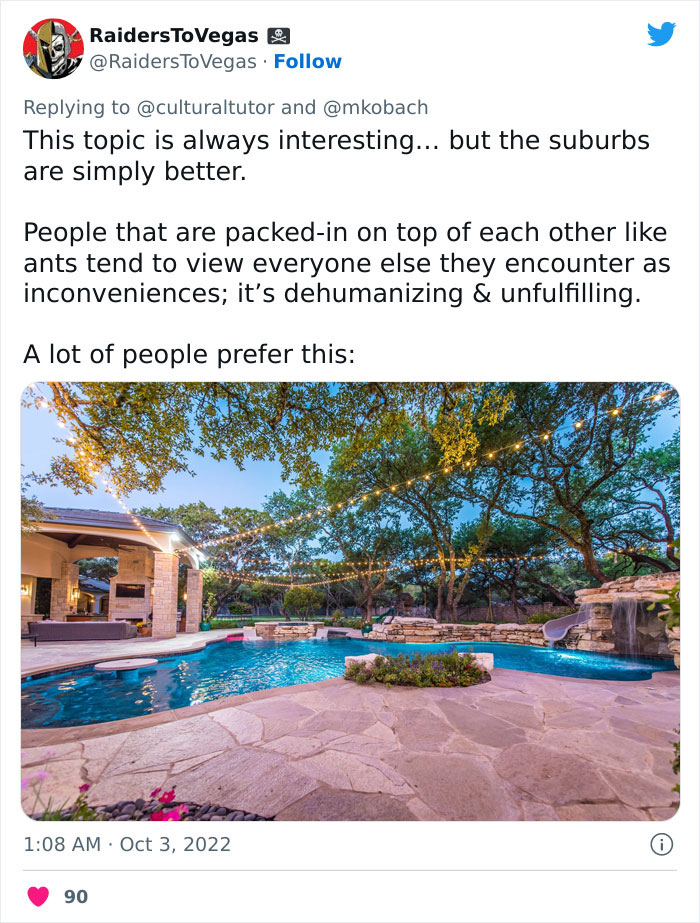

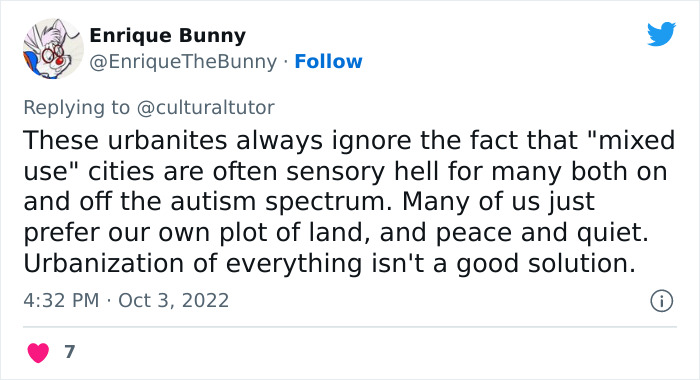

While others aren’t really excited about it, and their disagreement prompted an interesting discussion

Image credits: RaidersToVegas

Image credits: ASIAMTWEET

Image credits: 5coEn1

Image credits: kan_immanuel

Image credits: sam_edwoods

Image credits: maybe_dan_

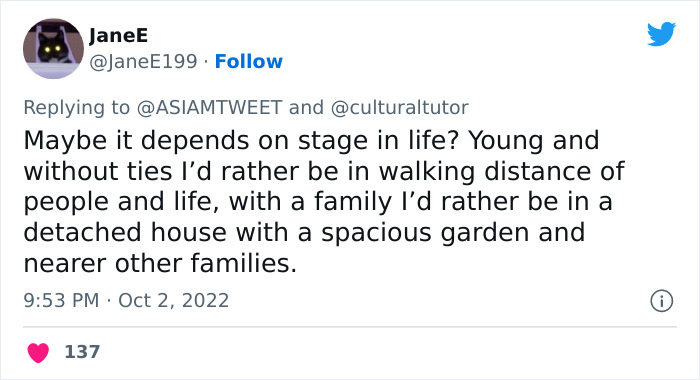

Image credits: JaneE199

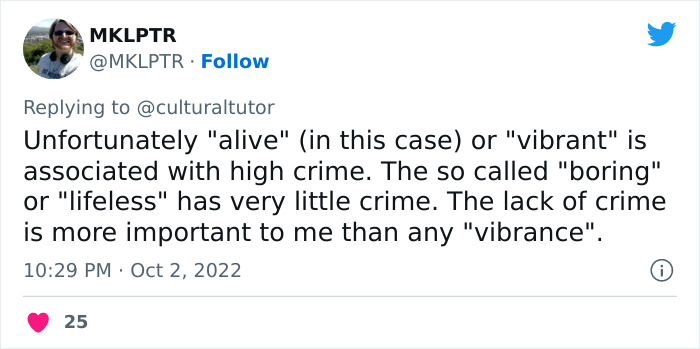

Image credits: MKLPTR

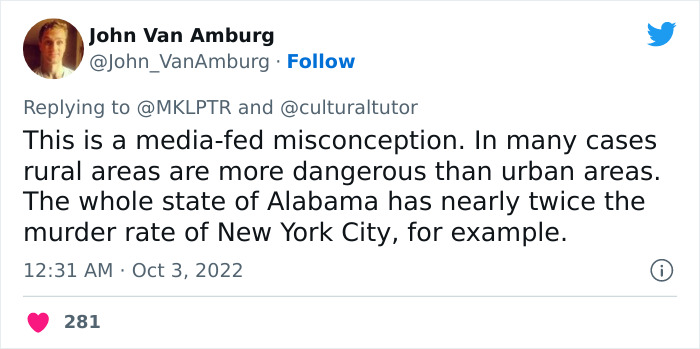

Image credits: John_VanAmburg

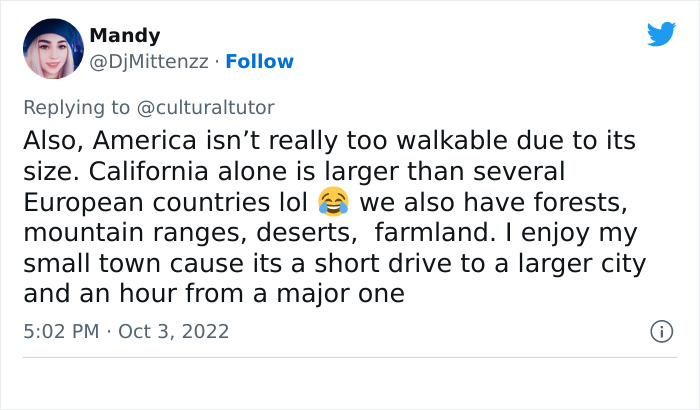

Image credits: DjMittenzz

Image credits: Schmoseph1

Image credits: unseen_carousel

Image credits: EnriqueTheBunny

Image credits: jedmcguirk

Mixed-used isn't just about having high density housing in city centres, with shops/business on the ground floor, and then apartments above. My experience of mixed-use is living in a house, with lots of facilities within walking distance. Within 15 minutes, there's schools for students aged between 4 and 18, nursery schools, a petrol station, small grocery shops, a butcher, a couple of take-away restaurants, a dentist, doctor, pharmacist, dog groomer, florist, garden centre, vet, churches, pubs, ...

Same. I lived in Berlin for years and within a 10 minute walk there were four supermarkets, a drugstore, a primary school and several doctors. If it wasn't for work or meeting friends, I'd have very rarely left the neighborhood.

Load More Replies...Some of you are arguing why or why not. The author states that some prefer single use and thats okay. What he's sayingis that we need both, but are lacking one.

Mixed-used isn't just about having high density housing in city centres, with shops/business on the ground floor, and then apartments above. My experience of mixed-use is living in a house, with lots of facilities within walking distance. Within 15 minutes, there's schools for students aged between 4 and 18, nursery schools, a petrol station, small grocery shops, a butcher, a couple of take-away restaurants, a dentist, doctor, pharmacist, dog groomer, florist, garden centre, vet, churches, pubs, ...

Same. I lived in Berlin for years and within a 10 minute walk there were four supermarkets, a drugstore, a primary school and several doctors. If it wasn't for work or meeting friends, I'd have very rarely left the neighborhood.

Load More Replies...Some of you are arguing why or why not. The author states that some prefer single use and thats okay. What he's sayingis that we need both, but are lacking one.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

91

37