8 Philosophical Thought Experiments That I Illustrated To Broaden Your Mind

I am a philosopher with a background in art (which I studied as an undergraduate). Philosophers use thought experiments, short stories that bring out intuitions. It is often not possible to do these experiments in real life, but by doing them in our heads we can learn something new about the nature of reality, about right and wrong, the existence of God and many other topics.

In this series, I’ve brought some thought experiments to life from various traditions.

All drawings are made with Paper 53, the iPad drawing app, and an Apple Pencil stylus. I’ve drawn several more.

The missing shade of blue

The thought experiment: A man has seen all colours, except one particular shade of blue. But he has seen other gradations of this colour, and if he were to arrange them in his mind, it would become clear that there’s a gap. Would he be able to fill in the color using his own imagination?

Significance: Hume came up with this thought experiment as a counterexample to his idea that we learn about the world through experience. If that’s the case, we should not be able to fill in the missing shade of blue but it seems we can. Curiously though, when I presented this drawing to friends, they thought the man’s sweater was the missing shade of blue, but it isn’t! So perhaps it is not so easy to fill in the gap after all.

Source: Hume, D.(1748). Philosophical essays concerning human understanding. London: A. Millar.

The experience machine

The thought experiment: The experience machine is a special device that can give you any experience you would like: do you want to be a famous jockey or a writer? Would you like to have many friends? The machine would make you believe it’s really happening, while you are in reality floating in a tank, electrodes attached to your brain. Would you plug into this machine for life? Your life would be preprogrammed to maximize your pleasure, but while plugged in you would think it is real.

Significance: What is happiness? Philosophers have debated this question, asking whether happiness is more than pleasure. Intuitively, it seems that pleasure might be sufficient for happiness. This position is called hedonism. But the experience machine thought experiment challenges this idea. If pleasure were enough, you’d plug yourself in the machine in a heartbeat. But most of us would hesitate. This is, according to Nozick, because we want more out of life: we have projects and life goals, and being plugged into a machine, living a fake life, is not a way to fulfill those. This seems to suggest hedonism is wrong.

Source: Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, utopia, and the state. New York: Basic Books.

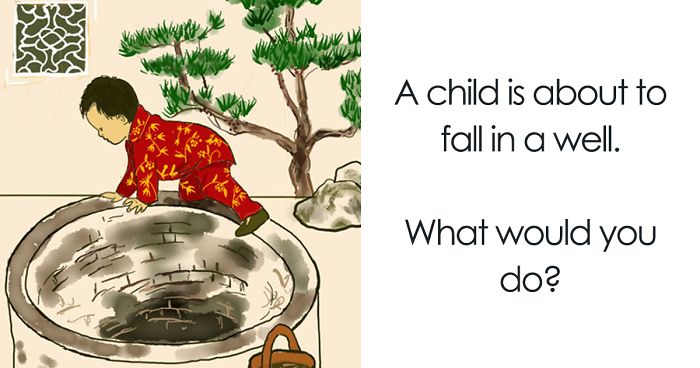

The child at the well

The thought experiment: Mengzi considers the case of a child who is about to fall in a well. Without exception, you would feel alarm and distress if you saw this. This would not be because you hoped to gain the favor of the parents, praise from neighbors and friends, because you dislike the cries of the child, or because your reputation would suffer if you did not try to help the child. From this, Mengzi concludes that the feeling of compassion is fundamental to humans.

Significance: Mengzi was a philosopher who lived in China in the 4th century BCE who followed in the tradition of Kongzi (Confucius). He developed the theory that humans have four roots (or “sprouts”) as he called them for morality: ren (humanity, compassion), yi (rightness), li (ritual propriety), and zhi (wisdom). These sprouts are present in all human beings, but they need to be cultivated in order to flourish, just like plants require water to grow. This thought experiment explores the idea that humans are innately compassionate (i.e., possess ren, 仁).

Source: Mengzi. (2008/4th century BCE). Mengzi: With selections from traditional commentaries (trans. B. Van Norden). Indianapolis: Hackett.

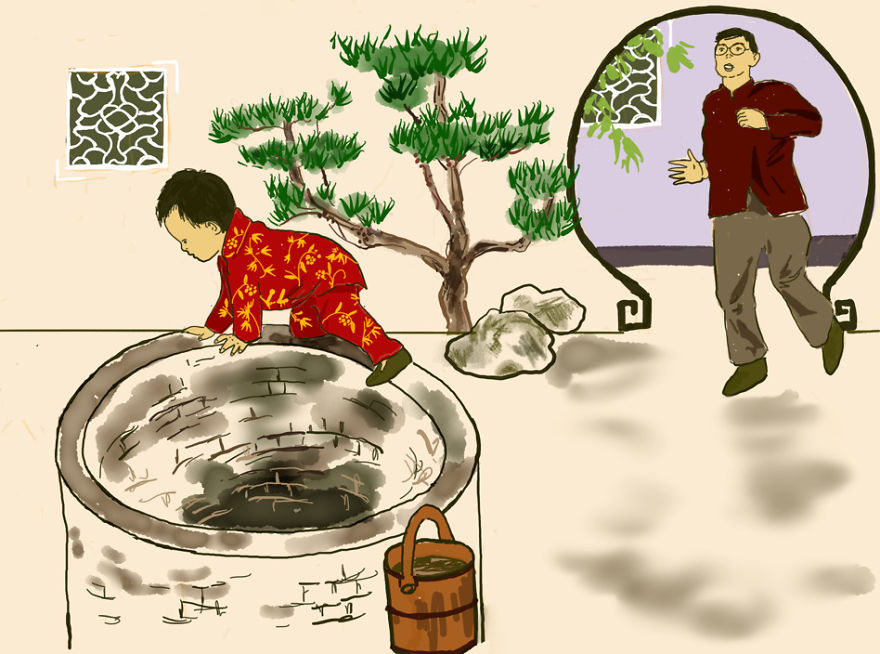

Sleeping beauty

The thought experiment: Sleeping Beauty takes part in an experiment, where researchers put her to sleep. She is told that a fair coin will be flipped. At each waking, she is put back to sleep with a drug that will make her forget that waking. They toss a fair coin. If it lands tails, she will be briefly awakened on Monday and Tuesday. If it’s heads, she will only be awakened on Monday. When she awakes on Monday, not knowing what day it is, what credence should she have that the coin landed heads?

Significance: You might think the chance of the coin being Heads is 1/2, after all, the baseline chance is 1/2 and Beauty does not receive any new information. But Adam Elga thinks Beauty’s credence should be 1/3. Beauty doesn’t know whether it’s Monday or Tuesday, so she should think that it could be either. Given that when Beauty awakes, P(Tails and Tuesday) = P(Tails and Monday) = P(Heads and Monday), the probability of each is 1/3.

Source: Elga, A. (2000). Self‐locating belief and the Sleeping Beauty problem. Analysis, 60, 143-147.

Otto and Inga visit a museum

The thought experiment: Otto and Inga both want to visit the Museum of Modern Art. Otto has Alzheimer’s. He consults a notebook that he always carries with him. His notebook plays the same role as biological memory usually does. It tells him that the MoMA is on 53rd Street. Inga consults her biological memory and forms the same belief. Now it would seem that Inga has a (tacit) belief about where the MoMA is before she retrieves it from her biological memory. But what about Otto? Although it is not stored in his brain but in a notebook, can we say that Otto’s entry about the museum’s location is a belief?

Significance: Are thoughts only things that happen in our brains, or also in the world? It seems in this case that Otto’s notebook works exactly the same way as Inga’s brain. So if we call Inga’s memory of the location of MoMA a belief, we should call Otto’s also a memory, even though it’s not in his brain. Now you can say that it is not a belief, because someone could tamper with his notebook or steal it. But Inga’s brain can also be affected, for instance, when she is drunk.

Source: Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58, 7-19.

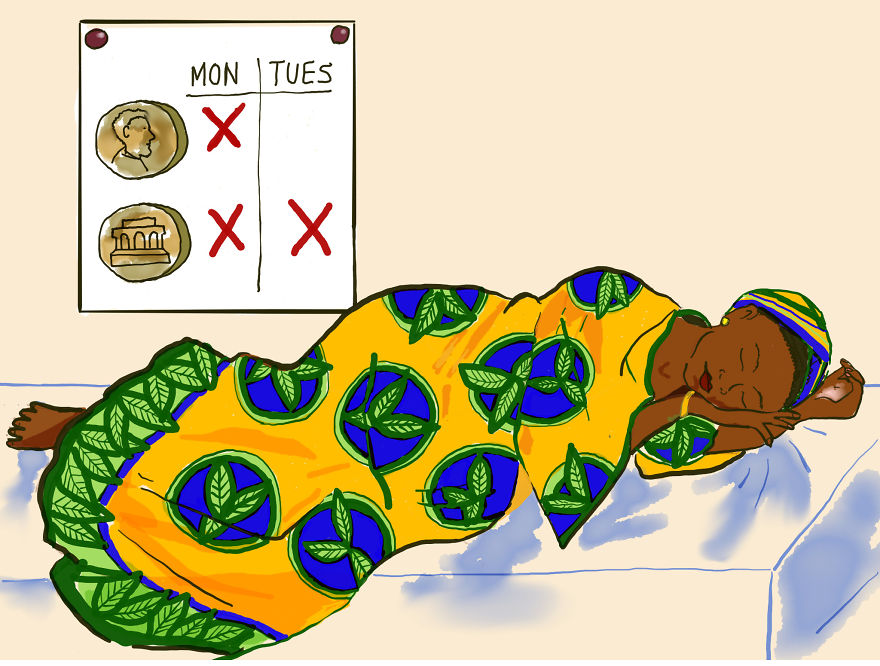

The invisible gardener

The thought experiment: Two people return to their long neglected garden. Although the garden looks wild, there are still many flowers blooming. One of them says, “There must be a gardener at work here.” The other replies, “I don’t think so.” To see who is right, they examine the garden carefully and ask the neighbors, who have never seen anyone at work. They also research what happens to gardens that are left without care. “You see,” says the skeptic, “there is no gardener.” The believer replies, “This gardener is invisible, and if we look more carefully we will find evidence that he comes, unseen and unheard.” The other one maintains there is no gardener. Can this dispute ever be settled?

Significance: It’s pretty clear that this is an analogy about the existence of God and how a theist and non-theist might see this differently. A theist might see design, an atheist does not. The question is to what extent we can see some features of reality as evidence for or against God’s existence. Is it really a dispute about facts, or two different ways at looking at the world, as a garden or a wilderness?

Source: Wisdom, J. (1944/45). Gods. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 45, 185-206.

The Russian nobleman

The thought experiment: A young, idealistic Russian nobleman intends to give his estates to peasants upon inheriting them. He also realizes that his ideals might fade. Therefore, he puts this intention into a legal document that can only be revoked by his wife, and he asks her to promise him she will not consent if he changes his mind later on. He even says that these ideals are essential to him: “If I lose these ideals, I want you to think that I cease to exist.” Now suppose that in middle age the Russian nobleman does ask his wife to revoke the documents. What should she do?

Significance: This is a puzzle about personal identity. Is the old Russian nobleman the same as the young man? Should his wife be released from her promise?

Source: Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The floating man

The thought experiment: This thought experiment occurs in several of Ibn Sina (Avicenna)’s writings. We should imagine a man who is brought into existence as an adult, out of thin air, so he has no earlier memories. He is floating in the air, his eyes are closed, he doesn’t hear anything, and his limbs and fingers are spread out so he does not feel his own body either. Now the question is: Would this man be aware of himself?

Significance: The question Avicenna is addressing is whether we are the same as our bodies. Avicenna thinks this is not the case, because the floating man would be aware of something. It can’t be of any bodily experience, and he doesn’t have any memories either. Therefore, the awareness must be of his soul.

814Kviews

Share on FacebookEither my English isn't good enough or I'm just too stupid to understand this article. How frustrating. :(

I actually think the floating man illustrates the lack of soul. The body is required for consciousness. Without the body, you cant even have the experiment because the idea of a fully formed consciousness springing into disembodied being we innately know cant happen. That means without a body (death) consciousness also ceases to exist.

But not feeling your body and having a non functioning (dead) body is'nt the same thing.

Load More Replies...The floating man is hardly an effective illustration. The floating man can feel his stomach whether he's hungry or not. He can flex his muscles. A lack of outside stimuli is not the same as a lack of stimuli altogether. Also, sensing a lack of stimuli is not the same as lacking senses. The man still sees, he sees his own eyelids. He hears his own breathing. He tastes his own saliva. He smells his own odor. In fact, given that he just popped into existence, these sensations would be very jarring. Now if you said a deaf, numb, and blind man was floating in a chemical that is entirely tasteless... then we're talking about the difference between a blinded man and a blind man.

Sure. Ibn Sina's point is still made or not made with your revisions.

Load More Replies...Either my English isn't good enough or I'm just too stupid to understand this article. How frustrating. :(

I actually think the floating man illustrates the lack of soul. The body is required for consciousness. Without the body, you cant even have the experiment because the idea of a fully formed consciousness springing into disembodied being we innately know cant happen. That means without a body (death) consciousness also ceases to exist.

But not feeling your body and having a non functioning (dead) body is'nt the same thing.

Load More Replies...The floating man is hardly an effective illustration. The floating man can feel his stomach whether he's hungry or not. He can flex his muscles. A lack of outside stimuli is not the same as a lack of stimuli altogether. Also, sensing a lack of stimuli is not the same as lacking senses. The man still sees, he sees his own eyelids. He hears his own breathing. He tastes his own saliva. He smells his own odor. In fact, given that he just popped into existence, these sensations would be very jarring. Now if you said a deaf, numb, and blind man was floating in a chemical that is entirely tasteless... then we're talking about the difference between a blinded man and a blind man.

Sure. Ibn Sina's point is still made or not made with your revisions.

Load More Replies...

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

172

43