There are eight billion people in the world, each with their own unique life story. New York City is home to over eight million people, but it's the most attractive urban center in the world for a reason. There probably isn't any other city so diverse and multicultural and so unique in its inhabitants and history.

So, today, we're featuring the renowned project Humans of New York. It's a well-known photoblog by photographer Brandon Stanton, who presents intriguing snapshots of New Yorkers in photo and story form. You'd think the tales from Humans of New York were from a movie, a story made up by a brilliant screenwriter. But this is real life, Pandas. As real as it gets.

More info: Humans of New York | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter (X)

This post may include affiliate links.

“I was just a neighborhood kid. There was no running water in our house. Or electricity. So in the evenings, when I came home from school, I’d sit out near the road. Across the street there was a hotel where foreigners stayed. I’d watch them play Frisbee. I’d watch them buy African souvenirs from the street vendors. Occasionally one of them would come speak to me. I was an inquisitive child. I liked to ask questions. So I think they found me entertaining. One evening an American girl came up to me and started asking me questions. Just small talk: ‘What’s your name?’, and things like that. But then she asked my birthday, and I told her: ‘November 19th.’ ‘No way.’ she replied. ‘That’s my birthday too!’ And after that we became friends. Her name was Talia. She’d come visit me every evening, and bring me chocolate chip cookies. She’d let me play her Game Boy. She’d ask about my family. She’d ask about school. I was the best student in my third grade class, so I’d show her my report cards, and she’d get so excited. She was the first person to take me to the beach. I’d never even seen the ocean before. We had so much fun together. But one evening she told me that she was going back to America. And I began to cry. She bought us matching necklaces from a street vendor, took one final picture, and promised that she’d write me letters. It was a promise that she kept. The first letter arrived a few weeks after she left. And there were many letters after that. She told her parents all about me. They invited me to America to stay with them for a month. They took me to baseball games, and amusement parks, and shopping trips. It was the best time of my life. When I returned to Ghana, they paid for all my school fees. They bought my books and clothes. They paid for me to get a degree in engineering. Now I have my own company. The Cassis family turned my life around. I was just some random kid they didn’t know, and they gave me a chance for my dreams to come true. I went back to visit them last year. But this time I didn’t need them to pay my way. I was giving a speech at MIT, because I’d been selected as one of their top innovators under the age of 35.”

I can't believe that I'm crying for someone that I never saw in my life. This is such a beautiful story and so heartwarming. I don't know you but I'm very proud of you. The wonderful family that gave him the chance of being where he is now, I just wish you all many blessings and thank you for helping this young man, and believe on him. I feel stupid for crying but it's a good crying

“It was just the three of us. And dad was a truck driver so he was gone most of the time. It could be a lot of stress. My mom was almost like a single mother. On my third birthday we moved to a small house outside of Denver. Next door there lived an older couple named Arlene and Bill, and they started talking to me through the fence. My first memory is Arlene handing me strawberries from her garden. It was a wonderful connection. After a few months, I knocked on their door, sat down in their living room, and said: ‘Will you guys be my grandparents?’ It was so silly. They could have laughed it off. But instead they started crying. They printed out an adoption certificate and hung it on their living room wall. That certificate remained until I left for college. They became so important to me. Their house was a refuge. Bill was the kind of grandfather that always smelled like oil. He taught me to drive everything. He was always fixing stuff. But he’d stop anything to sit down with me and have a glass of tea. Arlene was the type of grandmother that loved crafts, which was perfect for a kid. We were always putting tiny sequins on things. Both of them supported me in all my dreams. Through all my phases. They encouraged me to apply for college, even though I didn’t have the money to go. And when I got accepted, they presented me with a fund. They told me they’d been putting away money since the day I adopted them. Since I’ve become an adult, I’ve learned more about my grandparents. They both grew up poor. Arlene struggled with alcoholism when she was young, and that’s why they never had children. Their lives weren’t as perfect as they seemed through the fence. My grandmother passed away in 2013. It was two days before our adoption anniversary. My grandfather gave her eulogy. And at the end, he said: ‘Arlene leaves behind her husband Bill. And the greatest joy of her life-- her granddaughter Katie.’”

"Mom died on the first day of school. She’d been really sick that entire summer. And she passed away on a Monday. At 7 AM. Almost exactly the time I’d be leaving for school. I don’t think I fully grasped how traumatic it was for me. I was there when she took her last breath. I comforted my little sister while she said goodbye. And the next week I had to start classes at a brand new school. I was a junior at the time. All the teachers knew what happened. And they had told all the students, so everyone was pitying me when I showed up. I met Alex that very first day. We were in choir together. We became friends almost immediately, but we didn’t start dating until we were both cast as leads in Seussical The Musical. We became more serious during college, and we ended up getting married right after graduation. I felt so sad that my mom couldn’t see any of it. Every time a big event would happen, it would be like—she’s not here. And she’s never going to be here. I was a moody, s**tty teenager when she died. And I’m having this whole life where I become the person I’m supposed to be, and she doesn’t get to see any of it. She’s not going to see me graduate. She’s not going to meet my children. And it especially sucks that she’ll never get to meet Alex. We lit a lantern at our wedding to signify that my mom was still with us. It was a beautiful ceremony, and afterwards we took our honeymoon in Hawaii. A few days into the trip, I received a call from my oldest friend Meredith. She sounded excited. She’d just discovered a picture of our childhood soccer team, and there was a boy who looked just like Alex. When I showed Alex the photo, he confirmed that it was him—he’d played goalie on that team. I just started laughing. It was such a God moment. It was a moment when everything felt connected. Alex and I had known each other as children, back when my mom was still alive. The first thing I did was call my dad. I asked him if he remembered anything about the Swan’s Dermatology Soccer Team. ‘I remember the goalie,’ he replied. ‘During the games he’d always sit down in the net and play with the dirt. And your mother thought it was hilarious."

Brandon Stanton, the creator of Humans of New York (or HONY for short), started the project in 2010. After working for three years as a bond trader in Chicago and losing that job, he decided to move to New York to pursue his passion: photography.

His initial plan was to take 10,000 portraits and put them out in an interactive map. A photographic census of the city, as he himself described it. He admits that the plan might've sounded crazy. Even his friends and family were telling him: "So you're just going to take pictures of random people on the street and somehow that's going to equal profit? OK..."

“Oh God, he was my life. You couldn’t miss him. He was big. 6’3” and 200 lbs -- and he was so alive. Wayne always stopped for life. That’s one thing he taught me—if you want fullness in life, you have to stop for it. He’d pull over on the side of the road to explore a creek. Or to look at a piece of road kill. Or he might visit a friend to help fix a roof, and end up staying the entire week. By the time Wayne left, the whole house would be renovated. He could fix anything. He once found a Model T in the woods and had it working in days. He was a complete genius like that. But one unfortunate thing about Wayne—he wasn’t a doctor oriented person. So by the time we discovered the cancer, it had already spread to his lungs. We were arrogant at first. We thought we could beat anything. But it was only a matter of time. A few weeks before his death, we were hanging out, smoking hash, and talking about what to do with his ashes. Suddenly Wayne picked up the vial of hash, looked at it closely, and told us he had an idea. It took a lot to get that man down. Wayne wanted to live until his 54th birthday, and that’s exactly when he died. You can’t grieve for a man like that, so we threw him a ‘fun’eral. We had bluegrass music and two bushels of Chesapeake Bay crabs. And as a parting gift, every attendee received a vial of Wayne’s ashes. There were hundreds of them. We only requested that each recipient share where their vial ended up. Mine got mixed into some ink and tattooed on my finger. The other vials have gone all around the world: seven continents, so many bodies of water, the Wailing Wall, the Great Barrier Reef. Wayne’s in two different volcanoes. A sarcophagus in the Louvre. He’s even in the evidence room of a Georgia prison, because one of our friends got arrested with Wayne in his pocket. Wayne would have loved that. That’s such a Wayne place to end up. You could never contain him. Not when he was alive. Not when he was dead.”

“I became a mother without ever having sex. I was sixteen. My sister was older than me, and she was living a reckless life. By the time we found out she was pregnant, she was already three months along. And the baby was born premature—so there was no time to prepare. My sister went back to the street life, and everything fell on me. I became the mother. I was feeding him, changing his diapers, waking up in the middle of the night. My mother helped at first, but soon she had a stroke and lost all movement on her right side. The doctor told us she wouldn’t be able to care for a child. So she signed Aidan over to me-- right there in the hospital. I was only eighteen years old. I was taking care of my mom. I was taking care of my son. I kept it all very private. I didn’t tell my tennis coach why I had to quit the team. I didn’t tell my friends why I couldn’t take vacations, or go to parties, or go to college. I didn’t want the stigma. I started working four jobs. I pushed all my own feelings to the back of my mind just to make sure my son was OK. I couldn’t even grieve when my mom passed away. I had to think about him. I had to make sure he was fine. Since then it’s been the two of us. Aidan and I grew up together. He’s a great kid. He’s so respectful. I get stopped all the time in our building. Complete strangers tell me how much they love him. He holds the door for people. He helps people carry their groceries. He’s focused. He’s a go-getter. He gives one hundred percent-- just like his mom. When there’s something that has to be done, he gets it done.”

“I don’t blame the girls. Not at all. I get it, I get it. But I’ve always wanted a wife. And kids. And as I get older it starts to get more real—I’ve never had a girlfriend. I’ve always been the funny fat friend. It’s the one thing I’m good at. Making people laugh. It’s the greatest feeling in the world. Somebody is having a great time, and it’s because of me. I’ve always lived for that feeling: in elementary school, in middle school. But as I got older—something got twisted. All my jokes became about myself. When it was time to eat the cake at a birthday party, I’d joke about the size of my slice. When it was time to jump in the pool, I’d joke about taking off my shirt. I’d say: ‘The moon is coming out.’ And it always got a laugh. Which felt good, but it kind of sucks. Because I don’t think I’ve ever taken off my shirt without making a comment. It’s my way of protecting myself. Like: ‘No a**hole, you can’t make fun of me. Because I beat you to it.’ But I think it might have f**ked me up. All those jokes, all those years. Because it made everyone look at me as the fat guy. It made me look at myself as the fat guy. My twitter handle is ‘Fatrick Ewing.’ My bio says: ‘Fat white guy with glasses.’ It sort of became my identity. I’m just a fat, funny idiot. That’s what I think about myself. And I feel like that’s what everyone else is thinking too. Every time I’m in a waiting room, and the seat’s a little too small. Or when I walk into CVS. My anxiety gets so bad I can barely talk to the person behind the register. My therapist tells me: ‘You’re a good guy, you’re nice, who cares?’ And she’s right, I get it. But I also think if I wasn’t fat, I’d probably have a girlfriend. But I’m trying to love myself more. Every day I’m working on it. I make deliveries for my job, and let’s say I leave my scanner in the car. My mind is immediately gonna say: ‘You’re a fat a**hole.’ But I’m trying to stop myself. I’m trying to say: ‘No, you’re not. You just forgot. People forget.’ I’m trying to get back to Luke again. The nice, funny dude. Who loves his friends. And his family. Not Luke the fat guy. Just Luke, before he decided to bully himself.”

Negative thought patterns are so hard to shift! I hope he is able to rewire his thoughts into positive ones. No one is perfect! No one should expect perfection

Brandon also wasn't an experienced photographer. He had only taken pictures around Chicago and while traveling the East Coast. At first, he published all his photographs on his personal Facebook page. But when he started posting them on the HONY profile, that's when things took a turn.

Although a million followers didn't come in a day, Brandon knew he could strike gold with his idea, so he persisted. Not long after he established Humans of New York, he started including captions in his photographs. And soon after, the interviews and people's life stories followed.

“It’s not instant. It’s something you do over a period of time. It began with green accents. I’d mix green into my nail polish, and put green streaks in my hair. There’s a small school across the street from our house. And whenever I walked our dog Dylan, I noticed that the children responded to the green. They’d give me little, timid waves. Oh, I love children. Little, happy people. They’re just so naturally there. And they love green. They’re drawn to it. Children are always bringing me green things, and dropping letters into my mailbox. Sometimes I can’t even read the handwriting, but it makes me so happy. People make me happy. They’re always so loving and sweet. I’ve never met a negative person—I just don’t bother with that part of people. When someone approaches me on the street, I give them a hug, and say something nice. It’s all that I’m looking for. And it’s all that I find. It really makes a big difference in life, not to be closed up. It’s a way of life. Whether you become a doctor, or a lawyer, or a green lady, you’re accomplishing what’s in your heart.”

“My dad took his own life when I was fifteen years old. I’m sure it was traumatic for my mom, but she sort of just sucked it up. She’d already experienced a lot of heartbreak in life. She grew up in a dysfunctional household and became a caregiver at a very young age. So she was able to conceal her emotions and focus on supporting me and my brother. I was the good kid. I worked hard in school. I played three sports. And Mom supported me in everything I wanted to try. Not in a pushy way. More of a helpful way. So much of her life was just driving me places: practice, games, extra lessons. Unfortunately her relationship with my older brother was different. Jacob was defiant. He wouldn’t listen. He had a good heart but he was doing a lot of reckless, scary things. Jacob had been the one who discovered my dad’s body, and I don’t think he ever fully recovered. Five years later he took his own life. When my mom got that phone call, she came into the living room, laid on top of me, and starting crying. ‘Jacob just shot himself,’ she said. Both of us barely recovered. I began training for triathlons to deal with my grief. It had been my mom’s suggestion, but I think it inspired her. Because one morning she made herself go outside, lace up her shoes, and take a run. Later she told me that running gave her something to live for. She began to compete in triathlons herself, and eventually became a certified coach. Mom’s ultimate goal was always to finish an Ironman competition, but it didn’t seem possible. She failed on four different attempts. Nobody wanted her to try again. She was 68 years old. She was the oldest female competing in Ironman Texas, and they literally thought she could die. But Mom was determined to try one more time. I cheered her on the entire way. I walked alongside her while she swam the canal. I biked alongside her while she ran. I remember we were nearing the end of the race, and she had to get to mile eighteen by 9 pm, or she’d be disqualified. I was telling her to pick up the pace. But by then she knew. She looked at her watch, then she looked at me, and said: ‘I’m an hour ahead. I’m going to be an Ironman!”

“I never thought I’d come back to New York. I have a lot of bad memories here. It can be an ugly place. My ex-husband lives here. On September 11th I was on the street below the second tower. So there are things I’d just prefer not to remember. But recently my mother got sick and I came home to take care of her. I was in a bit of a rut at the time. I’d fallen away from my passions. I was just working to pay the rent. And one evening I was walking by the river and I passed a place called Hudson River Community Sailing. They offered free sailing lessons. I don’t know why I stopped. I was intellectually convinced that sailing was not for me. I was getting older. I was out of shape. But I decided to give it a try. And I got hooked on it. I got kinda obsessed with learning to sail. I remember the first time I was out there alone. It felt amazing. I was in the middle of the Hudson, the wind was blowing, I could see the whole city, and my hand was on the tiller. It seemed like I was doing something impossible. I’m not white. I’m not male. I don’t own a boat. I don’t even have money. But I’m in New York City and I’m f**king sailing.”

Today, the Humans of New York Instagram page is fast approaching 13 million followers. On Facebook, the audience is even bigger: around 17 million. Brandon spoke in one interview about how, in the early days of HONY, having 10,000 Facebook fans seemed like a massive success. Now, the number is a thousand times larger than what his definition of success was back then.

“My husband had a sudden heart attack a few months ago. It was just a few blocks from here. They called me in to identify his body and then just let me walk right out onto 7th Avenue. I felt so lost. My friends were wonderful and supportive but eventually everyone moves on with their lives. I don’t have children. And I’m not a workaholic. So I was left with this intense loneliness and void. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep. Then one day I started researching dogs that are good for grief and depression. And ‘poodle’ kept popping up. But when I went to the rescue fair, all the poodles were gone. There was this one old dog in the back that nobody was looking at. She was skin and bones. She was trembling and scared and mucus was running out of her eyes. She seemed so fragile. She reminded me of myself. I named her Grace because I think my husband sent her to me. She’s my first dog. She’s been pure joy. We spend all our time together. She’s gained her weight back. She comes with me to therapy. We’re getting better together.”

“I woke up with a gasp in the back of an ambulance. They’d shot adrenaline directly into my heart. Apparently I’d been dead for 2.5 minutes. The EMT’s were freaking out. My chest hurt from the electric paddles. And I was already in acute withdrawal. At the time, it had been nearly twenty years of addiction. I weighed 128 pounds, and I’m a six foot tall man. There comes a point when you’re given the gift of desperation. And that was it for me. Today is my 160th day clean. I’ve never gone this far before. One of the first things I did after getting sober was write my son a letter. He was raised by my parents. I told him: ‘You did nothing wrong. I was an addict. I loved heroin more than you, more than your mother, more than my own mother.’ And he’s forgiven me. He’s a good hearted kid. I think more than anything he just wants his dad back. He came to visit me in November. It was the first time I’ve seen him in seven years. He’s become my biggest advocate. He knows my day count. He texts me every day for a feelings check. He’s become my biggest motivation. I just don’t want my legacy to be ‘dope fiend.’ That can’t be what’s on my headstone. That can’t be how he remembers me. I don’t want my kids telling their kids: ‘Your grandfather was a heroin addict.’ I want them to brag about my sobriety. I want them to say: ‘That’s something he was, but he beat it.’”

“I’ve blacked a lot of it out. But I do remember that recess was a nightmare for me. My mom told me later that she would sometimes hide in the bushes, and when she saw me sitting by myself, she’d start crying. The diagnosis was ‘selective mutism.’ I’d get so anxious around people that I physically couldn’t speak. I’d get a rock in my throat, and it would feel like that moment right before you faint—when everything sounds so far away. It could be lonely at school. I was the only student with a full-time aide. I was the only one who held up a sign when the teacher called attendance. It doesn’t feel good to be different. But my parents did everything they could to minimize that feeling. Every night before I went to sleep, my mother would say: ‘You’re a terrific kid, and I love being your Mommy.’ When my school had a Halloween parade, she knew I’d be too anxious to do it alone. So she dressed up as Minnie Mouse and marched right alongside me. She was always very attentive to my emotions. But she was also a lawyer so she made sure that my rights were being respected. She knew that the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act promised a ‘free appropriate public education.’ And that’s exactly what she wanted for me. She once shut down my entire elementary school for an in-service day, and the entire faculty was taught to ask me ‘yes or no’ questions so that I could nod in reply. She wanted me in a mainstream classroom, having mainstream experiences. So that I would never be left behind. And by the time I hit 5th grade, I was able to speak. It didn’t happen all at once. But I grew more and more confident. I got better at making friends. I joined the debate team in high school. Recently I graduated from Cornell and completed my senior thesis on disability rights—which I defended verbally. All of this was possible because of my mother. She was beside me the entire time. I took the LSAT in January, and even though the test was five hours long, my mom waited in the lobby. She gave me the biggest hug when I walked out. When I asked her why she didn’t leave, she said: ‘I don’t know. I just wanted to be here. In case you needed anything at all.’”

But Humans of New York is not only social media pages. Stanton put the most captivating street photography and the accompanied stories in a book in 2013. In 2015, a second book was published: Humans of New York: Stories. With the love his project received online, it's no surprise both books were #1 New York Times Bestsellers. HONY also received an official proclamation from the City Council of New York for its contributions to New York City.

“Our community was hit first. Asian restaurants were empty long before other restaurants. Even on the subway I could sense that racism was on the rise. On television one night there was a story about an elderly man who was collecting aluminum cans—just to survive. He was robbed and taunted. His bags were broken. His cans were strewn all over the street. And he didn’t speak English, so he couldn’t even ask for help. It broke me. Because in his face I could see the faces of all our grandparents. In our culture there is a tradition of: ‘Never speak out. Never ask for help.’ If our elders were suffering, would they even let us know? I decided to call a service organization focusing on Asian elderly, and I asked: ‘How many meals do you need?’ They replied: ‘As many as you can cook.’ We started preparing 200 meals per week in our little 300 square foot apartment. Moonlynn cooks beautifully and efficiently, so she lovingly banned me from the kitchen. But I still wanted to help in some way. So I found a black sharpie, and began to write on the plastic containers. Traditionally our elders are very reserved with their affection. I can still make my father blush just by kissing him on the cheek. But since I grew up in America, I have the privilege of being more direct. I found the traditional Chinese characters for ‘We are thinking of you’ and ‘We love you,’ and I wrote them on every container. I thought it was important to use the word ‘we.’ I never signed our own names. Because I wanted it to feel like a whole bunch of people— an entire community who cared. And before long that’s exactly what it was. We found ten restaurant partners within a half mile who helped us prepare culturally relevant foods. And over the past eighteen months @heartofdinner has delivered 80,000 meals to our Asian elders. We weren’t able to personally write notes on each one. So we put out a call on Instagram, and 100,000 hand-written notes poured in from all over the world. We told people to go wild. Add as much character as you’d like. There were so many styles, and so many colors. But every note had two things, written in big, bold letters: ‘We are thinking of you.’ And ‘We love you.’”

Near the beginning of COVID, I would go to a small Asian grocery store. I got fantastic ingredients with no people around AND I got to support people who were being utterly demonized in my area for no reason. I still go there. Only place I can get the good king oyster mushrooms and dried shiitakes here.

“The first thing I noticed was a tremor. I’m a computer programmer and I kept accidentally hitting the shift key. Then I started to lose my sense of smell. And finally came the depression. My wife made me see a doctor. She said to me: ‘Either you get on an antidepressant, or I’m going to.’ That's when I learned I had Parkinson's. Over the years my tremors got worse. My voice got quieter. I had to quit working. My dopamine levels fell so low that I lost communication between my brain and face. I couldn't express any emotion. My daughter grew up without seeing me smile. I probably seemed distant. A lot of times I felt like I couldn't fit in with the rest of the family. Then a few months ago I had an experimental surgery. They inserted a wire in my head that stimulates the brain with electricity. Now all my emotions are coming back. I’m more talkative. I have more energy. I’ve cried more in the last few months than I have in the past thirty years. And for the first time in her entire life, my daughter can finally see me smile.”

“Crowds were the worst. Any little person will tell you that. There’s nothing worse than crowds: getting looked at, getting seen. People making fun of my family. All three of us are little people: my mother, my brother, and me. My mom raised us on her own. With no help. But she knew the struggle, and she would build us up every time we got bullied. Sometimes I’d even feel like killing myself. But she’d say: ‘You’re special. Your mother loves you. Your brother loves you.’ But my mom was also a thug. She was the muscle in our family. If we complained that people were staring at us, she’d say: ‘Look right back. Talk your s**t.’ Whenever I got in trouble for fighting, she’d never get mad. She’d say: ‘You defended yourself. That’s good. Now do it again.’ She encouraged us early to play basketball. First it was my older brother. Then it was me. There was this center in our neighborhood where a dude named Hammer ran a program. He’d make us read a book for thirty minutes—I hated that part, but then we’d play basketball. And that’s how I learned about my size abilities, not disabilities. If you’re a six or seven footer, and you aren’t perfect, I’ll time your dribble. I’ll steal it the moment it hits the ground. So you’ve got no choice but to dribble low. You gotta come down to me. And I’m already down here. This is my world. This is where I live. The guys in my neighborhood grew to respect me. I was never getting trash talked in the Douglas Projects. But when I started playing in high school, and we went to other arenas—the crowds could be cruel. My teammates would try to protect me, and motivate me. But there’s not much you can do with three hundred people chanting ‘midget.’ I hated walking out to the court. Any little person will tell you—crowds are the worst. But as soon as I made that first shot, they’d get quiet. Then I’d do it again, and again, and again. Then eventually the crowd would start to get on my side. Cause they’d never seen anything like me. They’d start cheering for me even though I was on the other team. And my mom would be in the stands, talking her s**t. Saying: ‘My son is smaller than all of you. And he’s kicking your ass!’”

The process of how Stanton interviews people has evolved as well. Back in the day, he used to only approach people on the street and ask them for their stories. Today, he does remote interviews as well. He's got over 200,000 emails in his inbox from people waiting to share their life stories.

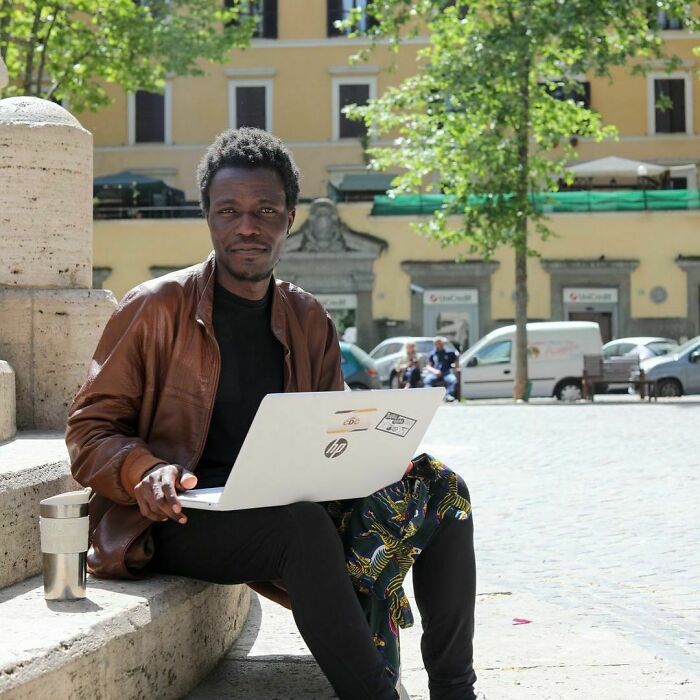

“I’m from a small country in Africa called Benin. I won the visa lottery to come here. I didn’t even know I was eligible. My brother entered my name and didn’t even tell me. I was studying to be a psychiatrist at the time. I assumed that I’d be able to continue with medical school. But when I arrived here, I found out that none of my credits would transfer. I had a choice: either go home and become a doctor, or start from the bottom. I didn’t speak any English. I didn’t have any money. But I knew if I could somehow make it here, my degree would be much more valuable. So I made the choice to stay. I began practicing English with my young nieces. The first thing I learned was: ‘I’m going to kick you.’ I got a job with a catering company and learned how to say ‘I’m here to deliver your food.’ I studied as many YouTube videos as I could during my free time. It’s been three years now. I’m almost finished with my bachelor’s degree. Just two classes left. At nights I work as a behavioral specialist in a mental health facility. I’m going to take the MCAT in September. My friends back home have all become doctors already, but I try not to think about them. I don’t want to lose my focus. I haven’t made it yet, but I’m making it.”

“It was my friend’s birthday, and everyone else was twenty-one except for me. So we went to a bar that wouldn’t check ID. It was called ‘The Clif Tavern,’ and it was a total dive. The cash register was from 1948. The owner was an old, weathered guy named Skip. He seemed very excited to have customers. He told us stories all night long. He talked about meditation, and racing cars, and being a black belt. I remember he was really proud that his brother’s dog had been in a movie with Cameron Diaz. By the time we left, all of us were in love with the place. We started coming back every weekend. And I was hanging around so much that Skip offered me a job as a bartender. He didn’t teach me much. He knew very little about business. He kept all his documents in an empty Budweiser box. But he was the spirit of the place. He gave great hugs. He called everyone his ‘kids.’ And he was a total hippie. Whenever he posted on social media, he’d sign it ‘Peace and Love.’ We worked together for ten years. Skip was with me when I met my husband. He witnessed our first kiss. He became like a father figure to me. And his bar became a huge part of my life as well. Skip used to always say that the bar was ‘killing him,’ and he kept threatening to move to Costa Rica. But he could never stay away for long. There were maybe six days in ten years that he didn’t come to the bar. So when he didn’t show up one evening, everyone knew that something was wrong. The police went to his apartment and found him unresponsive. He’d died of a heart attack. None of us knew what to do. I gave the eulogy at his funeral, and then left to go open the bar. All of us assumed it was the end of everything. But one month after the funeral, I got a call from Skip’s brother. He said he couldn’t sell Skip’s legacy to a stranger, so he offered the bar to me and my husband. Over the past few months we’ve renovated everything. We have a new tap system now. We’ve added a modern register. We’ve made a lot of changes, because we know that it needs to be an actual business if it’s going to survive. But we’ve also covered an entire wall with Skip’s photos and notes. Because we always want the place to feel like Skip.”

“My first end-of-life patient was a 97-year-old man. He had a much younger girlfriend; she was seventy-four. But they loved each other so much. Back when their spouses were still alive, the four of them had been great friends. They would double date together. And when their spouses passed away—the two of them became a thing. Every day she would come over for lunch. I’d always cook a little meal for them. I’d prepare the table; I’d lay out my little candles and my little flowers. As soon as she arrived I’d put on music and dim the lights, then I’d leave the room and go wait in the bedroom. They would cuddle and snuggle. And the beauty of it was—even though he couldn’t control his fluids at that point, she never minded the smell. Her love for him was so great that they would still kiss and all that good stuff. When the doctors said that it was time for him to go to hospice, he said he didn’t want to go. He told them that he wanted to come back home and die with me. I was with him in the end. My patients never die alone. Never, ever. One week after his passing I was hired by his girlfriend’s family. She had terminal Alzheimer’s, and I ended up staying with her for seven years. I fell in love with her. We were family, just family. She used to be a tap dancer. We’d sing together. And if she didn’t feel like singing, I’d sing. Even near the end, she always knew when something was wrong with me. When I wasn’t being the Gabby that she knew-- she would always know. When the doctors said it was time for her to go to hospice, her children said: ‘We want her to die with Gabby.’ In the final days she wouldn’t eat, she’d lock her jaw. But she would always eat for me. One night I could see the fright in her eyes, and I knew it was time. My patients never die alone. Never, ever. So I climbed under the covers with her. And she passed away in my arms.”

Before, it was all about the story, now, Stanton says, readability plays a huge part too. "It can't just be a compelling story, but it has to be a story that's compelling and will work in short-form. It has to fit in 2,200 characters, which is the character limit on an Instagram caption," he said in a 2020 interview.

“My sister was the only girl in our family. There were four of us—but between me and her it was different. We were the closest in age, so we shared a lot. We shared the same bedroom. We shared the same food. And we shared lot of secrets. That’s why I was so disappointed that she didn’t tell me about the pregnancy. She was already seven months along when I heard the news from a friend. When I confronted her, she tried to deny it. She only told the truth when I promised that I’d support her no matter what. My niece was born on December 19th. She was named Aseda, which means ‘thanksgiving.’ After the birth, everything seemed fine. My sister and I were talking on the phone. She was sending me pictures. But on Christmas Eve the complications began. Her condition worsened quickly. The doctors said she needed to go to another hospital. But she never made it. She died next to me in the back of an ambulance. Before she passed, she told me-- in our native language, she said: ‘Bro Ato, anything that you’d do for me, please do for my baby.’ These words were written on my heart. Everything that followed was like a bad dream. I’d just lost my sister, and suddenly I was taking care of a preterm baby. I had to feed the child. There was no formula in the hospital. I had to search everywhere. I didn’t have time to sleep. I didn’t have time to mourn. But somehow I found the strength. There are some things that you don’t know are within you. Aseda is almost four months old now. My girlfriend has been helping me every step of the way. She has been amazing and I’m so thankful. Our plan is to legally adopt Aseda. It’s a very personal thing for me. I want the child to stay with me. I’ve been with her from the very first hour. This is what I need to do for the baby. For my sister. And for humanity.”

(Tema, Ghana)

“I’m a physical therapist for severely disabled children in the South Bronx. Their observation skills are so keen. They understand more than you know. But they rarely get spoken to, or hugged. Often they aren’t even treated like humans. When the world can’t understand what you want, it kind of ignores you. I had one student named Tamisha who was stuck in a wheelchair. She could only move her eyes. She couldn’t speak, but I could basically read her mind. Tamisha was very intelligent, and very sarcastic. If someone in tight clothing got on the elevator, she’d roll her eyes. And giggle. I’d have to pretend I didn’t know why she was laughing. We grew so close over the years. On Halloween I dressed her up as a butterfly, because that’s how I saw her. She was trapped in this body, but she was a soul with so much depth and so much future. Many of these kids have nowhere to go when they graduate from school. They lose their social lives, and sense of purpose. They’re imprisoned in their bedrooms for the rest of their lives. When Tamisha graduated I wanted to do something for her. Her economic situation was not good. She was being raised by a single father. But Tamisha was completely immobile, so it’s not like I could just get her something cool on Amazon. But my husband and I came up with another idea. We went to Home Depot and got paint, and butterflies, and rainbow decals. And we completely transformed her bedroom. We wouldn’t let her look. We made her sleep in the living room. But at the end of the weekend, when Tamisha’s father carried her in--- she started going wild. Her eyes lit up. She’s making all kinds of vocalizations. Her father is holding her, and he’s crying. It was a miracle. Every makeover is a miracle. We’ve done about 20 of them now. We always manage to find the money. We always manage to find the volunteers. Somehow they always come together in a magnificent way. Our process always begins with an interview process. We ask the person: what makes you happy? What colors do you love? What are your favorite things? We figure out exactly what they want. We let them design their dream room. Then we become the instruments who bring that dream to life.”

Two of my brothers had a severe disability that affected motor/muscle control and they were largely non-verbal. My older brother was able to say a few words when he was little but then as his condition progressed, he couldn't even keep his mouth closed and his tongue stuck out a lot. My younger brother could make sounds like mmm or ahhh but that's about it. They were both in wheelchairs (though the older one could crawl and stand until he was about 8/9) and although little kids would come and interact with them, most adults would just talk over them to my mum. About them, but never to them. My mum ended up making a sign for their wheelchairs introducing them and saying 'I may not be able to talk, but I can understand everything you say'. Like the girl in this story, they had a great sense of humour and were very sarcastic, they rolled their eyes a lot. When my little brother was 4 we applied for Make a Wish for him. They said he wasn't eligible until he was 5 but they got in touch...

“He wasn’t my type. He was nerdy. He was wearing Converse. And he talked like a robot. But it had been over a year since anyone had paid attention to me. And I was enjoying our conversation. I never told him that I had a daughter. I just wanted to be ‘that girl at the brewery.’ For one afternoon, I didn’t want to be the young, single mother. And it was nice. It was nice to feel wanted again. When he asked if we could go out sometime, I didn’t even hesitate. But I started feeling nervous as soon as I got home. Because I started thinking about all the places a date could lead, and I knew I had to tell him. So I sent him a text. It said: ‘You should know I have a daughter. Things aren’t good with her father. I’m not asking you to fill that role, but if you want to cancel the date-- we can.’ There were twenty minutes of silence. And then he replied: ‘It is what it is.’ Just like a robot. Then he wrote: ‘If the date sucks, we never have to talk again.’ We made plans to meet at a famous brunch place. They didn’t even serve alcohol, which made everything twice as awkward. We agreed to take it slow. And to just have fun with things. He made it very clear that he wasn’t in a place where he wanted to be a dad. And that remained his official stance for about three months, until he met her. It’s been over two years now. So he’s been there her entire life. They’re obsessed with each other. She constantly wants to talk with him about everything. She wants me to call him when she farts. She wants to be a Wildcat fan because he went to Arizona. And when we find a shell on the beach, she’ll pick it up. But it’s always for him—not me. And he loves that little girl. But that’s not surprising. What’s surprising is that he loves me. Roo is easy to love. She’s so young. She doesn’t withdraw or want space. She doesn’t have scars. She’s never been abandoned. She accepts love without question, and she gives it without question. They love each other so much. So much that it makes me nervous. Sometimes I’ll ask him: ‘Do you just love me because you don’t want to lose her?’ And he’ll say: ‘No. I love her a ton, and I love you a ton.’ He always says it very calmly. Just like a robot.”

Although Humans of New York is Stanton's main project, he's done similar ones in other cities and countries as well. In 2014, he went on a 50-day tour with the U.N., photographing and interviewing people from 10 countries in the Middle East region. In his blog, he includes stories from people from Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, Uganda, Jordan, The Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Kenya, Ukraine, India, Vietnam, Mexico, and Jerusalem.

“He had five daughters. And whenever he came home from a work trip, we’d all line up to give him a kiss. But he always kissed my mom first, because she was his ‘first love.’ Then he went on to his ‘second love,’ and his ‘third love.’ On weekends we’d all pile into the car and take these long road trips. We’d drive for hours, and the whole way he’d be singing to my mother. It was a normal thing for us, because we were used to it. But that kind of affection wasn’t normal in our culture. We used to have these karaoke parties with our extended family, and everyone else would sing normal songs. But Papa would choose these old, romantic Bollywood songs. And he’d sing directly to Mama. She loved every second of it. She’d get dressed up for him. She’d put on her brightest red lipstick. And she’d do her hair just as he liked it—even after she got sick. The tumor was deep in her brain. After every surgery, more and more of her would slip away. When she couldn’t walk properly anymore, she grew embarrassed of her limp. So Papa held her hand wherever they went. He’d sit next to her bed, and stroke her cheek, and recite the Quran until his lips went dry. Some nights he’d fall asleep sitting up in his chair, but then he’d wake up, and begin praying again. In her final moments, when she was slipping away, he leaned close to her and whispered: ‘You won’t be alone. I’m coming with you.’ I heard him say it. And I got so angry. It seemed selfish to me—as if the rest of us weren’t worth living for. But all his children were grown. Most of us had our own families. And I guess he felt like there was nothing left for him. Every day he visited Mama’s grave, even though we told him not to. He applied for the plot next to her, and every few hours he’d ask if the cemetery had called. He was obsessed. When the paperwork finally arrived— I rolled my eyes. But he got very quiet. For the next two days he barely said a word. Then on the third morning, he walked in our front door and told me he wasn’t feeling well. I bent down to help him with his shoes, but he collapsed on the floor. There wasn’t time for him to suffer. Because by the time the ambulance arrived, he was already gone.”

“I was just a kid from a little cow town in Montana, but I was convinced I knew everything. So I got into a little tangle with my dad and ended up joining the Air Force. They stationed me out in Spokane, Washington. And not long after I arrived, me and a couple of buddies decided to take a day trip out to Liberty Lake. It was a real neat little lake. Fifteen feet deep and so clear that you could see straight to the bottom. We started playing a little football on the beach, but then we noticed three girls out on a floating dock. So we decided to swim out there. The water was really cold. And about halfway to the dock, I charley horsed in both my legs and started to sink. I thought for sure I was going to drown. When I woke up, I was laying on the dock, and one of those girls was staring down at me. Apparently she’d seen me go under, jumped in her brother’s boat, and pulled me out by the hair. That girl was named Dolores. She saved my life in August of 1952, and she saved me again and again for the next 64 years. We raised four children together. Not only was she my wife, but she was also my mentor. I was just a kid from Montana. She turned me into a good man. Her personality, her love-- I’m talking deep love-- for me and the children, changed me one inch at a time. And she never lost that heart for rescuing people. She worked with youth. She worked in street ministries. Whenever somebody was in a little bit of trouble, Dolores would jump right in. I know she sounds a bit like Wonder Woman—but she was. We were inseparable. People called us ‘joined at the hip.’ Two years ago she passed away. And I’ll tell you the only reason I’m still living—because I know, that one day, I’m going to wake up in heaven, and see Dolores looking down at me one more time.”

I'm not religious like that, but I DEEPLY respect people like him and their believes, instead of discussion who's right and debating religion angrily, I would love to see more people just accepting people like him, religion is fine as long as people aren't hurting others because of it, and if nothing else, the love this man still have for his wife is beautiful, so was the love between the Muslim couple were the man follow his wife in death a few days after she died etc.

“Leah was my absolute best friend. She was an only child too, so it was this next level sisterly bond. Her boyfriend Rasual became like a brother as well. He valued Leah’s friendships—so we became like a family. One night the two of them were driving home and lost control of their vehicle. Both of them passed away-- instantly. My grieving process was very hard. People were worried about me. The everyday, basic things became so difficult. I wasn’t cooking dinner for my kids. I wasn’t painting very much. Then one year after their death, I got invited to exhibit at an art show in Cleveland. It was on the anniversary of Leah’s funeral. I’m not even sure why I accepted the invitation. While I was getting ready in my hotel room, I remember saying a little prayer. I said: ‘Leah, I love you so much, but help me get through tonight without talking about you. Just one night.’ I arrived at the event and noticed that I’d be sharing my wall with another artist. His name was Bonic. He was deep in conversation with someone. The first thing I noticed was his voice. It was a very strong voice. And it was so familiar. I introduced myself, and told him: ‘This is going to sound crazy, but your voice sounds just like my friend who passed away.’ And he said: ‘Do you mean Rasual?’ It turns out that he’d known Leah and Rasual for years. He recognized me from their memorial service. That was over a year ago. Since then, Bonic and I have done so many collaborations. We’ve been all over the world together. He’s great with my kids. He’s my soul mate. Without question—he was the reason I was at that show. At the end of that night, I went back to my hotel room, and I wrote an entry in my journal. I wrote the date, and a single line: ‘Leah—did you send him to me?’

Stanton has also done several series on specific populations. Invisible Wounds is a project about American veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Pediatric Cancer series features stories about the patients, parents, family members, and professionals in the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

“I first ran for Congress in 1999, and I got beat. I just got whooped. I had been in the state legislature for a long time, I was in the minority party, I wasn’t getting a lot done, and I was away from my family and putting a lot of strain on Michelle. Then for me to run and lose that bad, I was thinking maybe this isn’t what I was cut out to do. I was forty years old, and I’d invested a lot of time and effort into something that didn’t seem to be working. But the thing that got me through that moment, and any other time that I’ve felt stuck, is to remind myself that it’s about the work. Because if you’re worrying about yourself—if you’re thinking: ‘Am I succeeding? Am I in the right position? Am I being appreciated?’ – then you’re going to end up feeling frustrated and stuck. But if you can keep it about the work, you’ll always have a path. There’s always something to be done.”

“I knew right away something wasn’t right. When they plopped her on my chest, she was amazing, and alive—but she looked like a skinny pink frog. The only way to feed her was to drip milk in her mouth, 24/7. Those first weeks I was getting such little sleep that I began to have hallucinations: babies on the ceiling, babies on the wall. My husband’s job was to hunt down the diagnosis, while I kept her alive. The blood tests suggested two rare genetic conditions. He had a harder time with it than me. Optimism felt like denial to him, so he got lost in the research. But I tend to be a magical thinker. Maybe too much at times. I love Disney World. I worked on Sesame Street. I draw comics for a living, and make children’s books. I’ve even written a letter for after I die. It says: ‘Don’t be sad. We’re given this life and bad things happen, but we get to be with our families and look at trees.’ I’ve heard people ask: ‘Why bring a child into this world?’ With climate change, and all that. Would you choose to be born? My answer is yes. Even during the apocalypse I’d want to be alive. So I could have a few more minutes in the shelter, with my family, watching on TV as the fireballs fall from the sky. Maybe I’m weird like that. My husband is a little weird too. So it just makes sense that now we have this weird, magical kid. Dalia is 2.5 now. She wears her little helmet, and braces. We take little walks, and see the city, and look at trees. Her condition makes it hard to wake up in the morning, so we get to have thirty minutes of huggy time. And any time she smiles it’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me. It’s not easy. There’s a lot of doctor visits. Therapies every day. But I danced when I was young, so I’m used to repetitive movements. Everything in my life just makes it seem like I was meant for this child. And it’s impossible to predict what will happen. There’s such a wide spectrum with her condition. When we asked the therapist if she’d ever walk, we were told: ‘Miracles happen.’ But Dalia is walking now. So I’m optimistic. I think things will work out. I think she’ll live independently one day. Either that, or I get to live with my best friend forever.”

“I was five when he became a person in my world. I didn’t know exactly who he was. I just knew that there was someone around that was making my mother smile. I had to look way up to see him. I’d never met someone so strong. He’d tell me to hold onto his wrist, and he’d lift me into the sky with one hand. He worked at an auto shop, airbrushing designs onto the side of vans. I think he dreamed of being an artist. But he needed something more stable. So after he decided to marry my mom, he became a cop. He never lost touch with his creative side. He was always building things around the house—making things look fancier than we could afford. He built my first bike from scraps. He encouraged me to read. He encouraged me to write. He loved giving me little assignments. He’d give me a quarter every time I wrote a story. Fifty cents if it was a good one. Whenever I asked a question, he’d make me look it up in the encyclopedia. One day he built a little art studio at the back of our house. And he painted a single painting—a portrait of Sting that he copied from an album cover. But he got busy with work and never used the studio again. He was always saying: ‘when I retire.’ ‘I’ll go back to art, when I retire.’ ‘I’ll show in a gallery, when I retire.’ But that time never came. Dad was a cop for twenty years. He was one of the good ones. The kind of cop you see dancing on the street corner. Or skateboarding with kids. But in 1998 he was diagnosed with MS. First there was a little weakness. Then there was a cane. Then there was a wheelchair. It got to the point where he couldn’t even hold a paintbrush. We did his hospice at home. He seemed to have no regrets. He’d been a wonderful provider. He’d raised his daughters. He’d walked me down the aisle. During his final days, we were going through his possessions, one by one. He was telling me who to give them to. I pulled the Sting painting out of an old box, and asked: ‘What should I do with this?’ His response was immediate. ‘Give it to Sting,’ he said. All of us started laughing. But Dad grew very serious. His eyes narrowed. He looked right at me, and said: ‘Give it to Sting.’ So I guess that’s my final assignment.”

The creator of Humans of New York has also done a series on people living in prison. For Inmate Stories, Stanton talked to and photographed the inmates from five different federal prisons in the U.S. He's also done projects on Syrian Americans and refugees in Greece, Hungary, Croatia, and Austria.

“After my grandmother passed away, Dad stepped out of the hospital for some fresh air. Then he said a prayer and asked my grandmother to send him a sign. When he opened his eyes, there was a dime at his feet. And after that day-- he began to look for dimes everywhere. I was six years old at the time, and he’d always get me to help him search. And whenever we found one, he’d say: ‘Bubby sent it to us!’ Then we’d add it to a little clay jar that I made. Sometime when I was in third grade, my parents sat me down and told me that Dad had cancer. I remember sitting in the guidance counselor’s office during recess. Apparently he’d already been sick for several years. It was a rare type of cancer. And it was aggressive. It would go away for two months at a time, but it would always come back. But even the people who knew him had no idea. He never let it stop him. He worked really hard. He woke up every morning at 4 AM to use the elliptical. Unfortunately his last few years lined up with my angsty teenage years. I pushed him away a lot. I wanted to hang out with my friends. But he kept trying. And things did get better between us. He was really silly and affectionate. He’d burst into my room while I was studying, singing at the top of his lungs, using a bottle of shampoo as a microphone. He’d always ask me to get coffee. Or breakfast. And I’d usually say ‘no.’ Because it’s hard when you have a terminally ill parent. You think about it all the time, but it’s the last thing you want to think about. And there’s this knowledge that the closer you become, the harder it’s going to be. He died when I was sixteen. It was November 30th. I remember walking around the parking lot at his funeral, staring at the ground. There wasn’t a dime anywhere. And it really pissed me off. I was looking at the sky. Shouting at the sky. But nothing. We found over 300 dimes when he was alive, but I couldn’t find any after he died. I searched everywhere for an entire month. Then one day I had a really bad day. So I decided to visit his grave for the first time since his funeral. I parked my car, walked down the steps, and found my dad’s plaque. Then I looked down at my feet. And there it was.

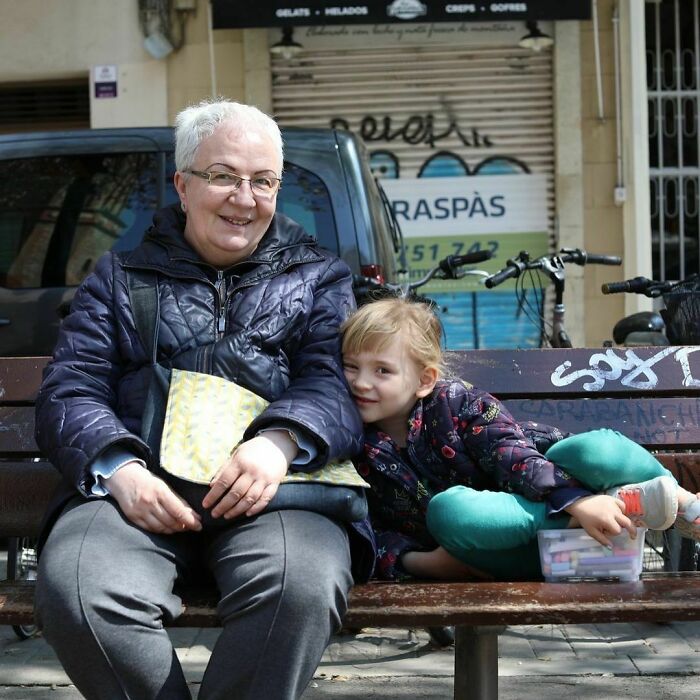

“Both of us are really shy. We were working at the same office when we met. I’d do anything to walk by her desk. And she’d do the same. I’d ask her for advice on certain projects. We were flirting the entire time but neither of us wanted to admit it. Then one night we decided to take a walk together after work. We ended up sitting on a bench just like this, and we had a very intimate conversation about our lives. We were so honest with each other. I talked about my weaknesses. And mistakes that I’d made. And plans for the future. We were sitting in front of town hall, and both of us agreed that it would be a great place to get married one day—whenever we met someone. The whole time I had my arm along the back of the bench, not quite touching her. It was so cold outside, but neither of us mentioned it, because we didn’t want the night to end. When the conversation finally finished, I walked her to her car. It was a ten minute walk. I tried to act relaxed but inside I was really nervous. The whole time I was thinking about kissing her. Should I do it? Should I not? Then finally I decided on a hug. But it was a deep hug. Extra deep hug. That night I went back home, and said to my roommate: ‘That’s her.’” (Paris, France)

I like how their outfits are matching- opposite: gray pants, khaki coat. Gray coat, khaki pants!

“I don’t know why my mother hated me. She had a sickness that you could not see. But she convinced me that I was sick. And that everything was because of me. And that I’m a monster. She criticized everything. My way of eating. My way of speaking. My way of dressing. Anything that brought me joy-- she would deny me. If I defended myself, she would hit me. I was terrified of lunch and dinner because that’s when I had to face her. I spent my entire childhood alone. I just played with my cats in the garden. Or sat on the floor of my bedroom. I’d try so hard to leave my body because I didn’t want to be on earth. And that’s when the spirits and fairies would come to me. Even Mother Mary came to me. I was never afraid of them. They’d comfort me. I remember being seven years old, sitting alone beneath a tree, talking to the fairies. Another little girl walked up and asked what game I was playing. That’s when I realized nobody else could see what I was seeing. And it’s been a very lonely existence since then.” (Paris, France)

Humans of New York is also a documentary, released on Facebook Watch in 2017, called Humans of New York: The Series. It includes videos of Stanton interviewing people on the streets of New York, a whopping 1200 of them. Hearing the people tell their stories in video format adds a new layer to the whole project. In 2017, it was reported to be the most popular series on Facebook Watch.

In exploring the infinite variety of human experiences and challenges depicted by Humans of New York, we are reminded of the unpredictable surprises life throws our way. Just like Teresa Such's unexpected culinary adventure, where the mishap with an unfortunate cake turned into a humorous anecdote shared with many, we can often find humor and shared understanding in our missteps.

Delve into Teresa's story to see how sometimes comedic attempts at perfection can lead to unexpected connections.

“It all began when my Grandpa Moe made a wrong turn. He was 93 years old, but he was still driving to and from his butcher shop. And one night he missed his turn in the dark. That’s when I offered to start driving him home. But he misunderstood me. Because the next morning he called at 7:30 AM, and asked: ‘When are you picking me up?’ That was the beginning of me coming here every day. The shop has been in our family for a very long time. But it was barely running by the time I arrived. Moe could still prepare the meat, but I’m not sure people even realized the place was open. He saved every piece of paper, so even the refrigerators had files in them. But thankfully he had guardian angels in the neighborhood. People were always stopping in to make sure he had water, or coffee. And there was always a neighbor to sit with him while he closed the store. It wasn’t really making money, but I think this shop is what kept him going. My first priority was to clean everything. He didn’t like that very much. He thought I was ‘messing everything up.’ He’d already started to lose his memory, which frustrated him. He’d always prided himself on telling stories and remembering names. But he was still so young at heart. We’d put on records from the 40’s and 50’s, and he’d remember the songs. And he was so gentle with me while I learned the business. Whenever I felt overwhelmed, he’d say: ‘piano, piano,’ which means slow in Italian. He taught me how to saw a lamb in half. And how to pick out meat at the market. He could get impatient sometimes. But if he ever lost his temper, he’d always apologize before the end of our car ride home. We worked together for 2.5 years. But during the first week of quarantine, my whole family got COVID. And Grandpa Moe passed away two weeks later. It was right before Easter. And when I came back to the store, there were so many flowers at our door. It was a little scary because the streets were empty. And I kept the door locked because I was all alone. But loyal customers kept stopping by, to see if I needed anything. And at night, when it was time to leave-- there was always a neighbor to sit with me while I closed the store.”

“My daughter was about to graduate high school when I lost my husband to a motorbike accident. She wanted to go to university but there was no one to support us. I’m an old-fashioned person. I’m not very smart. I only graduated from junior high school. But I wanted her to be better than me. I asked our relatives for help, but they all refused me. Out of desperation I approached my landlord. And she was the only one who supported us. She told me: ‘Get back on your feet so your daughter will have a chance.’ She loaned us half the tuition. The other half I earned by working morning to night. I was doing laundry. I was doing dishwashing. I was going around selling cookies and cakes. My daughter graduated recently and became a midwife. All my hard work paid off. We’ve been paying back the loan. And a few months ago she asked for my bank account number, and she’s been putting money in every week.” (Jakarta, Indonesia)

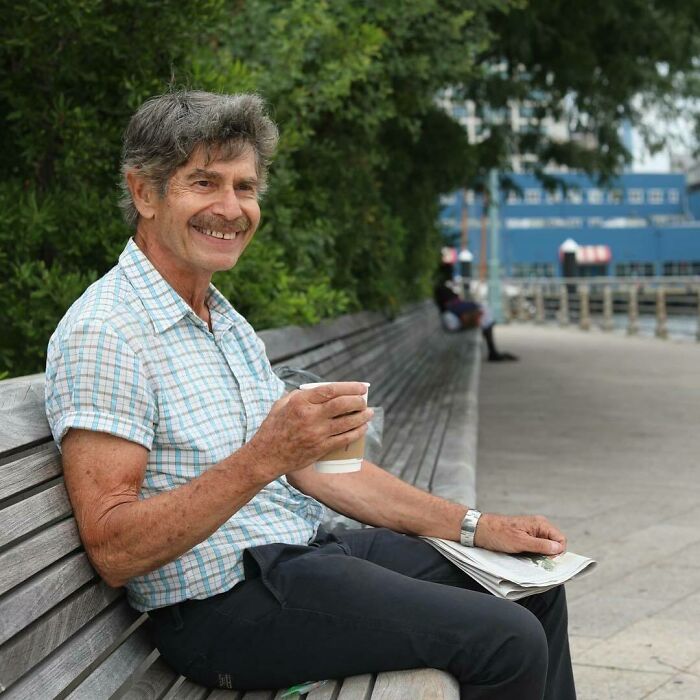

“I’m ninety-six years old. I’d rather just take a pill and get it over with. Whenever I tell that to my wife, she pretends to slap me in the face. But I’m ready to go. And I’d like it to be sudden. I’ve had a good run. I was lucky enough to share my life with someone. She’s ninety now. We’ve had a lot of time together. We have seven grandchildren. Eight great-grandchildren. But there are just so many things I can’t do anymore. I have the money. I have the time. Just not the ability. Whenever I walk, everything hurts. I enjoy sitting here in the park. I think about all the friends that I’ve lost. People come talk to me. Time passes by. But I’m ready. I’m not scared of it. I’d like my soul to go to wherever the souls go.” (Barcelona, Spain)

“If I’m away too long, he’ll come find me. Even if I’m just upstairs watching my program on television-- he’ll wander up to see what I’m doing. And we’re always holding hands. Even if we’re just sitting on the train or the bus, he'll always find some way to touch me. Just to let me know he’s right there. That he got me. He might not even notice that he’s doing it. But I always do.”

Even when I’m seriously pissed with my husband, the feel of his hand in mine will never not be comforting

“We had dorm rooms next to each other freshman year. We mainly just played a lot of board games: Risk, Scrabble, Scattergories, a Trivial Pursuit game from the 1980’s-- which everyone sucked at. But we became best friends, and the next year decided to get a house together. That’s when things started to get tense. We began sitting closer together. We were touching more. We’d play with each other’s hands. Never holding hands-- but playing with hands. And we’d even fall asleep in the same bed together. There was a time that she told me goodnight, and I swear I felt her brush my lips, but by the time I opened my eyes she was out of the room. Neither of us had ever dated a woman. And I was terrified to try anything. We were such good friends. There was always this fear that if I voiced the desire, it would ruin our friendship. But one night we were out for drinks at a hotel where Al Capone used to stay. I was feeling pretty drunk, so I leaned over and said: ‘Sometimes I feel like I want to kiss you.’ And she replied: ‘Sometimes I do too.’ I didn’t say a thing. I wasn’t even sure that I’d heard her correctly. I just kept thinking: ‘Oh my God, it’s happening. It’s happening.’ Then once we finished our drinks, and started walking home, I stopped her in front of a bridge. I said: ‘Shall we do it here?’ It was December 12th, 2002. And even though we got married five years ago, that’s the day we celebrate as our anniversary.”

“My father called me ‘stupid’ a lot. Even when I’d bring home good grades, he’d say things like: ‘You’re smart, but you don’t know anything.’ I just wasn’t a big reader like him. He always had a book in his hand. Math was my thing. During lunch I’d go to the junior high library and sit on the floor with puzzle books. Now I’m a teacher, and I’ve taught every math class in the high school curriculum. A few years ago I was teaching my precalculus class, and I stumbled upon a set of numbers that generated ellipses with identical positioning in both the rectangular and polar coordinate systems. So I turned them into variables, wrote a two-page proof, and had my work published in a journal called The Mathematics Teacher. Take that, Dad.”

“Early childhood was chaotic; my brother and I endured a lot of abuse. Having one another helped. It was sort of: ‘Hey, at least there’s another human with me.’ We’ve handled our trauma differently over the years. My brother doesn’t trust authority, and he’s been arrested in seven different states. It usually involves some sort of power struggle with police. His last altercation was in Texas, and it landed him in solitary confinement for 18 months. It couldn’t have come at a worse time. Law school was kicking my ass. I was living off student loans, so I didn’t have the cash to go visit him as often as I wanted. I was drinking a lot. On weekend nights I’d stumble out of the subway at 3 AM or 4 AM, after the bars had closed. And Abe, my coffee cart guy, would be outside my station-- setting up for the day. He’d talk s**t to me before giving me a bagel and water. Then he’d walk me to my building to make sure I got home safe. He was my late-night safeguard in addition to my morning barista. The 8AM line was long, so we had a cheat system. I’d send him a text when I was leaving my place, and he’d have a paper bag with my food and coffee waiting for me inside the cart window. On Saturdays when it was slower, I’d sit on a crate behind the cart and we’d talk for hours. He became a best friend. He introduced me to his wife and children. I learned that his cart supports some of his family back in Egypt, and that’s why he hadn’t taken a day off in almost twenty years. I told him about my family too. Mainly I talked about my brother’s incarceration. Others advised me to cut him off, but never Abe. He told me not to give up on my family. During one of our Saturday conversations, I mentioned that I couldn’t afford to go see my brother. I was careful how I phrased it, because I didn’t want Abe to think I was asking for help. But the following Monday morning when I grabbed my paper bag from inside the window, there was another bag rolled up inside. I thought it may be a chocolate croissant that he’d sneak in sometimes, but it was $3000. I said, ‘Abe no f**kin’ way,’ but he wouldn’t take it back. ‘Pay me back whenever,’ he said. ‘And go see your brother as much as you need.’”

“I used to walk 12 kilometers to school. And every day along the side of the road, there’d be an old woman who was so sick that she couldn’t move. The sun would beat her. The rain would beat her. And nobody would help. I was only seven years old. I couldn’t stand it. But my parents wouldn’t agree to bring a total stranger into our house. How are we OK with people dying like chickens on the side of the road? Millions of people in this country haven’t even taken a single meal today. I can’t stand it. I’m thirty now and I’m struggling. But I’m still trying to help even though I don’t have money. I taught myself to treat diabetes with herbs. I’ve treated ten people so far who can’t afford the hospital. But I want to do more. I’ve given myself a timeframe. I’ve been working at this conservation center for three years now, and I’ve learned a lot. In a few years I’m going to open my own center. I can use the profits to build houses for people who have no place to stay. Each person can stay for a year. Maybe if they can just rest their head for a month, they’ll find a way to feed themselves. And if they eat for a week, they’ll start to reason like a human being. At the very least they’ll see that it’s possible to be loved by someone. And maybe they’ll realize that God loves them too.” (Lagos, Nigeria)

And there are billionaires like the muskrat who don’t have half the compassion and integrity of this young man. This is another thing”God” needs to answer for

“My mom threw me out of the house at seventeen for getting pregnant, then had me arrested when I tried to get my clothes. Then she f**ked the head of parole to try to keep me in jail. She was some prime pussy back then. But the warden did some tests on me and found out I was smart, so I got a scholarship to go anywhere in New York. I chose the Fashion Institute of Technology, which I hated. But by that time I was already getting work making costumes for the strippers and porn stars in Times Square. All my friends were gay people, because they never judged me. All I did was gay bars: drag queen contests, Crisco Disco, I loved the whole scene. And I couldn’t get enough of the costumes. My friend Paris used to sit at the bar and sell stolen clothes from Bergdorf and Lord and Taylors, back before they had sensor tags. So I had the best wardrobe: mink coats, 5 inch heels, stockings with seams up the back. I looked like a drag queen, honey. One night a Hasidic rabbi tried to pick me up because he thought I was a tranny. I had to tell him: ‘Baby, this is real fish!”

Many of you will remember this young lady. Tanqueray caused quite a stir a few months ago when she dropped some truth bombs on us, while wearing a hand-beaded faux mink coat that she made herself. What you don’t know is what happened afterward. Tanqueray—whose real name is Stephanie—sat for a series of twenty interviews with me, during which time I transcribed her entire life story. And whoa boy, what a story. Stephanie is a born performer, so we were initially going to make a podcast out of it. But unfortunate circumstances have required a change in plans. Stephanie’s health has taken a bad turn, and she’s in a really tough spot. So I’m going to tell her story right here, right now. It’s the most ambitious storytelling I’ve ever attempted on the blog. It will unfold over the course of 32 posts. But if there’s anyone who can hold an audience for an entire week—it’s Tanqueray. As her story is shared, we will be raising money to ensure that Stephanie can live the rest of her life in comfort and dignity. Stephanie has a lot of urgent needs, so her care will be expensive. But her story is priceless. If the series adds any value to your life over the next seven days, please consider making a contribution to our fundraiser through the link in bio. ‘Tattletales From Tanqueray’ will begin tomorrow.

They raised 2.7 million dollars and the book (by Brandon Stanton (Humans of NY) and Stephanie Johnson) is for sale @Amazon.

“Adults guess and assume that I’m not going to understand things just because I’m a little kid. And it can be frustrating. Cause, like, I really want to know stuff. Or even when they do talk to me about things, they’ll always try to ‘tone it down to my level.’ They especially avoid the heavy themes like sex and death and cannibalism and stuff. But that’s stuff I want to talk about. I’m really fascinated by the Donner Party. The entire expedition-- really. What did it feel like to eat people that you knew? I’m also fascinated by how the human mind deals with death. It’s like people shut down the idea of death completely, and insist that heaven and hell are places after death. But death is death. And everyone after death is dead, because consciousness is just your brain. And even if there is evidence of life after death, it’s difficult to assess. We’re going to be incredibly biased toward any information that suggests there’s something more. Because we are so desperate to believe it.”

I remember being fascinated by similar things when I was a kid. When we studied Dracula in school it was Vlad the Impaler I was most interested in. One time after visiting my brother's grave, I said to my mum that I wanted to be mummified when I died. She said I couldn't because that wouldn't be legal here. As I grew up I swung the other way. I felt no connection to my brothers by visiting their graves, just by living my life. I don't want a gravestone, I want to be cremated, because t's cheaper, and minimal embalming if possible. I don't really like the idea of my ashes being spread in one particular place, but I've had to come to terms with the fact whoever I leave behind will want to remember me in their own way. For some reason (maybe because my brothers died young) I've always imagined my mum would be planning my funeral so I've mentioned things I want/don't want.

“My wife gave me our son while she’s at a doctor appointment, so I have the chance to watch him for a little bit. I’m going to bring him to lunch at the office and introduce him to my colleagues for the first time. I’m sure some of them won’t care, but I’m excited about it. It’s like my two worlds are coming together. Being a father is a huge part of who I am right now. And my colleagues are the people I spend the most time with. I’m excited for them to see why I’m so happy to go home every day.” (Berlin, Germany)

“My dad said we could do something special for my 6th birthday. ‘Anything you want,’ he told me. I think he thought I was going to say ‘ice cream.’ But I said I wanted to go to New York City, and two weeks later we were on a plane. We spent the morning of my birthday shopping at the American Girl store. Then we went to lunch at Balthazar. Afterward my dad wanted to stop by an old Irish bar called McSorley’s. He’s not a creepy alcoholic father or anything. He designs bars for a living, and he’s always looking for inspiration. It was early in the afternoon so the bar was pretty calm. My dad ordered a beer, and an old man came and sat down at our table. He looked very Irish: suspenders, loose pants, red face. And he was very, very kind. He showed us a few card tricks. He loved that my last name was O’Brien. He kept calling me a ‘real life Irish princess.’ At the end of our visit we took a photo together. And as he was leaving, he told me: ‘I’m Matty Maher. The owner of this bar. And I’ll be expecting to see you again on your 21st birthday.’ As soon as we got home, we mailed Matty the photo of us. My dad and I visited McSorley’s a few more times over the years— anytime we were in New York. I’d always send Matty a postcard in advance, to let him know we were coming. But after awhile I wasn’t a little kid anymore. The bouncer got less and less excited about letting me inside, so we stopped going. I didn’t see Matty for several years. But when my 21st birthday came around, my dad took me on one last trip to New York. I sent Matty a postcard to let him know we were coming, but I wasn’t sure he’d remember me. It was early afternoon when we walked in the bar. It was almost empty—just like it had been fifteen years before. Matty was nowhere to be seen. And I was coming down with strep throat, so I wanted to leave. But it was just like a movie. The doors swung open, and Matty came in like a ray of sunshine. He brought a plate of cupcakes over to our table. He showed me a framed photograph of the two of us—it had been hanging in his office all these years. And then he gave me a birthday card. Inside he had written: ‘I’ve finally met a woman who keeps her word.’”

When my mum and stepdad started dating, we went to a local pub bistro for lunch one day. He walked in and said 'wait a minute', walked over to the booth, then came back and said 'I built those'. I don't think he had been there since building them decades earlier and was often stoned/drunk back then. Then he went on to tell us he knew what the inside of a number of 'gentleman's' (strip) clubs looked like because he built the stages and booths there too. He hadn't been back to any of those either, until after that conversation a friend had a buck's night. He hated it as soon as he entered and tried to go back to the hotel room instead but didn't have the key or money or something so he just walked around for a few hours.