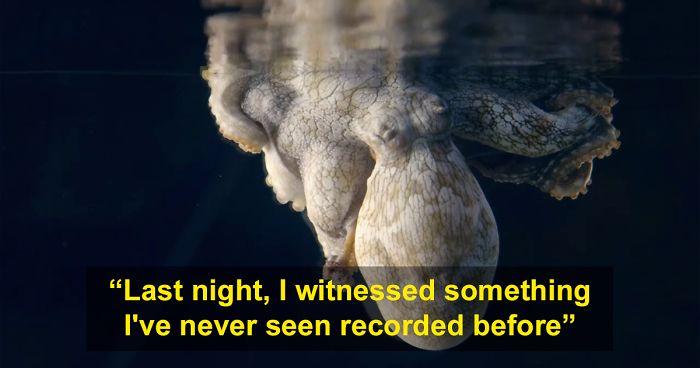

Someone Films This Octopus Changing Colors While Dreaming And It’s Spectacular

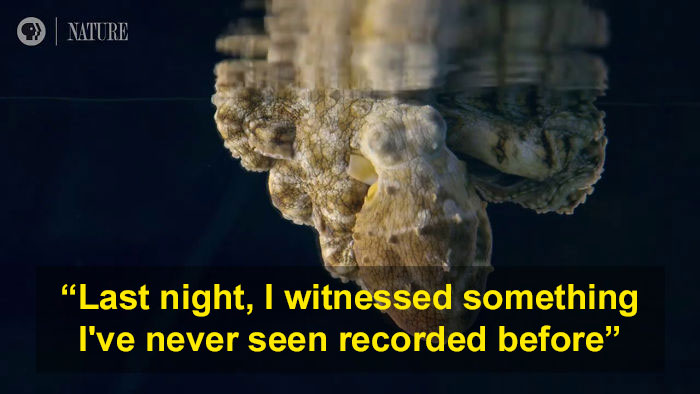

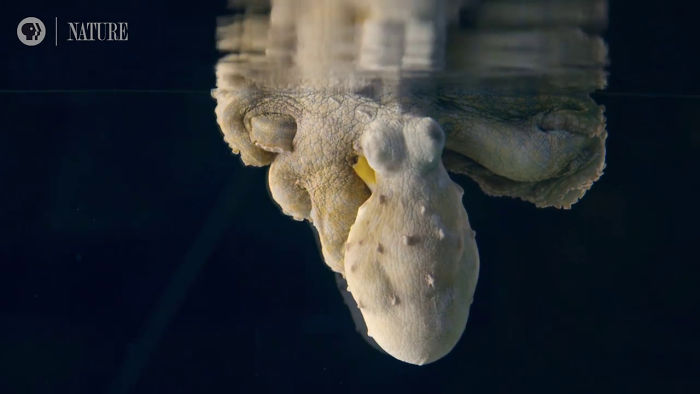

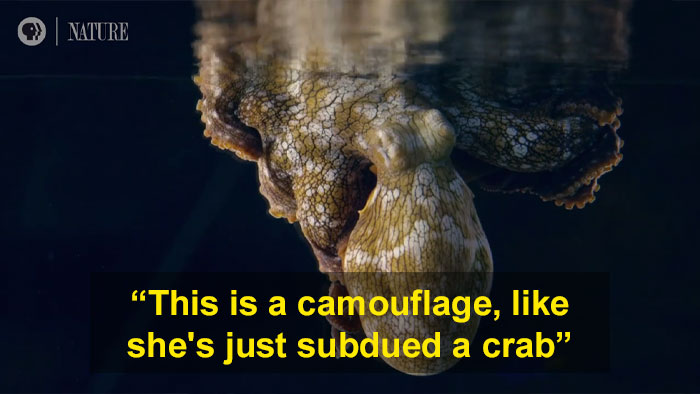

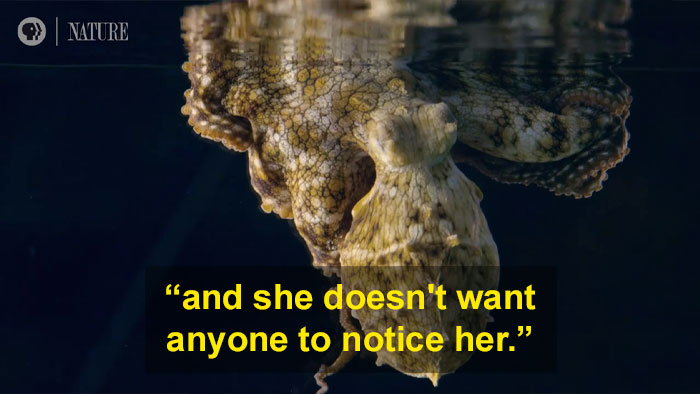

Interview With ExpertOctopuses are masters of camouflage. They can trigger cells underneath the surface of their skin to change color. However, it might be that these soft-bodied creatures aren’t putting on a light show just to confuse predators. Recently, PBS released a mesmerizing clip of a sleeping cephalopod changing her color multiple times.

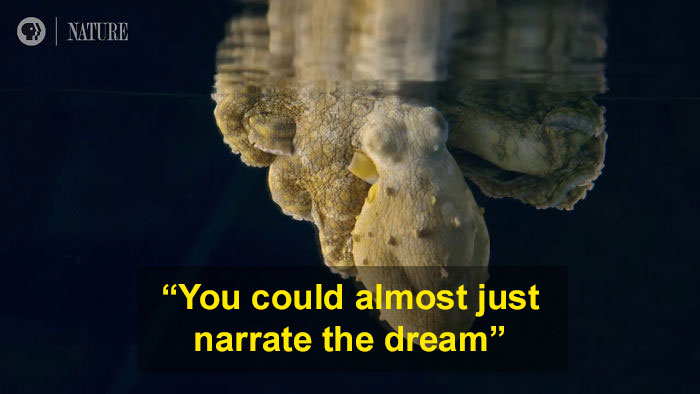

What makes it even more amusing is marine biologist Dr. David Scheel’s narration. He tries to guess what the octopus — Heidi — was dreaming about.

The video was taken from the documentary Octopus: Making Contact, which premieres on PBS on Oct. 2. It features Dr. David Scheel, a professor at Alaska Pacific University in Anchorage, and Heidi, the octopus he’s raised.

In the documentary, Heidi demonstrates her abilities of solving puzzles, using tools, and escaping through small spaces. She also seems to behave like a family pet, as she learns to recognize faces, getting excited when humans come near her tank. She even exhibits an inclination to play with Scheel’s daughter.

Octopuses typically activate their camouflage superpowers in response to changing conditions around them. So, does this video of a resting octopus’ color display mean that it’s dreaming about something? Maybe. Even though research into cephalopod sleep and dreaming has grown quite a bit over the years, there still isn’t enough evidence to say for sure if they dream the way we do.

“First, let me say that I am not a sleep biologist, and so not an expert in these behaviors,” Dr. Scheel told Bored Panda. “I can speak to the questions about sleep and octopuses from a passing familiarity with some of the literature on sleep in animals.”

Unlike humans, octopuses don’t have a centralized brain. Instead, they have multiple “brains,” their bundles of neurons are distributed in their limbs.

“It does appear that many animals, and perhaps all animals with nervous systems, must sleep. Sleep has been noted for example in two different species of jellyfish, which of course are not fish but cnidarian invertebrate animals related to corals and anemones,” Dr. Scheel said.

“Sleep can be recognized behaviorally, and studies have found that both octopuses and their relatives cuttlefish have behaviors that satisfy the definition of sleep: they become quiescent and less responsive to disturbance but can be roused. After a period of sleep deprivation, they sleep longer to catch up. And their brains are active during these sleep behaviors.”

Dr. Scheel wanted to be a marine biologist since he was a child. “I read a lot of science fiction, and when I was twelve, working with marine animals seemed as close as I was likely to get to studying aliens.”

“Heidi was an octopus who lived with my daughter Laurel and I for the making of this film. She loved to chase a ball on a string around her tank.”

Dr. Scheel added that he has always liked octopuses. “What’s not to like? Octopuses are inherently interesting creatures. I have also spent time studying African lions, bats and rodents, killer whales, seals, seabirds, and crabs, among other animals. They are all interesting. Over the years though octopuses have stayed a constant while work with the other has come and gone.”

Currently, Dr. School focuses on fund-raising for equipment improvements in the aquarium lab at Alaska Pacific University. “I will be conducting further research on octopus behavior and cognition. I am also working to publish more results from the field work on octopus behavior in both Alaska and Australia. I am being asked about collaborating on investigating sleep behavior. That would be a new direction for me.”

Watch the video of this magical creature below

People had a lot of pleasant things to say about it

126Kviews

Share on Facebook

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

399

36