This Fake Doctor In The Early 20th Century Used Premature Babies For People’s Entertainment And Saved 6,500 Lives

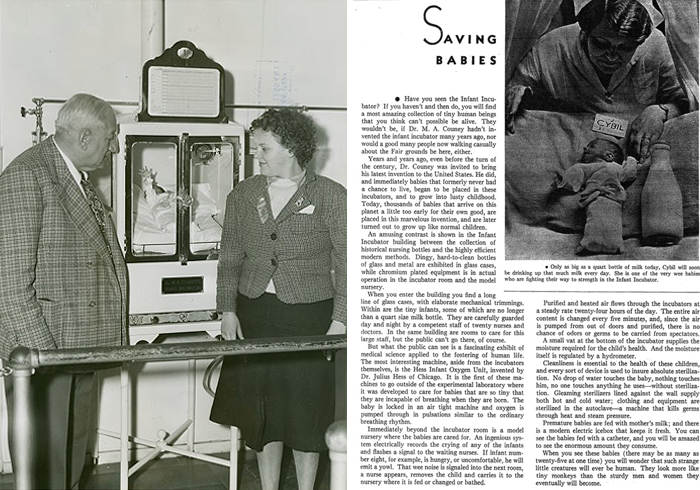

“When you see these babies (there may be as many as twenty-five at one time) you will wonder how such strange little creatures will ever be human. They look more like tiny monkeys than the sturdy men and women they eventually will become,” an article from the World’s Fair weekly about incubator babies read. This article named “Saving Babies” was published back in 1933. At that time, hospitals did not treat prematurely born babies and as one woman who was born prematurely recalled, “They didn’t have any help for me at all. It was just: you die because you didn’t belong in the world.” But her father knew a man that could take care of her – Martin Couney.

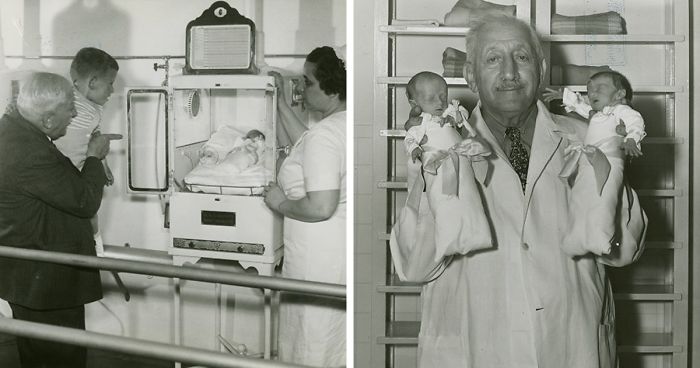

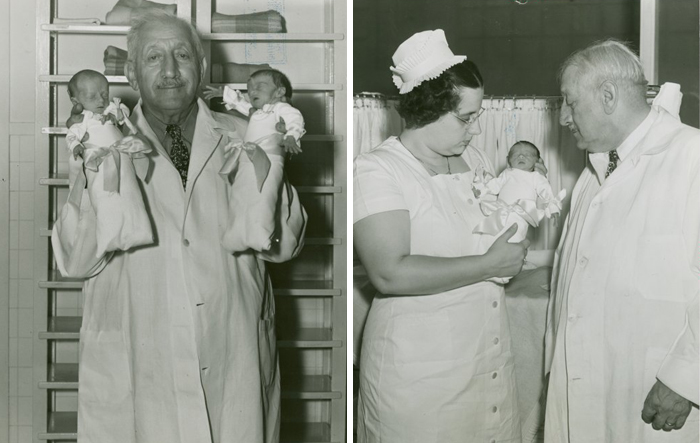

This man helped to save 6,500 prematurely born babies by showing them off as a sideshow attraction

Image credits: New York Public Library

Martin Couney does not appear to have had any medical credentials. Although he did often claim to be a protege of the French doctor Pierre-Constant Budin – a man who popularized incubators in Europe – there was never any evidence for this claim. Incubators were developed for babies back in the 1880s, in Paris. Martin Couney first displayed them at the Berlin Exposition in 1896. From then on, he traveled to more exhibitions but finally settled in the US in 1903 to run the sideshow of babies-in-incubators, which continued on until the early 1940s.

It would cost 25 cents to see the babies and the money was used for their care and treatment

Image credits: New York Public Library

Visitors would pay 25 cents to see the tiny babies, thus funding their care. As shocking as it may seem now, self-appointed physician Martin Couney (later dubbed ‘the incubator doctor’) displayed a struggle between death and life, which went on to became one of Coney Island’s most popular attractions.

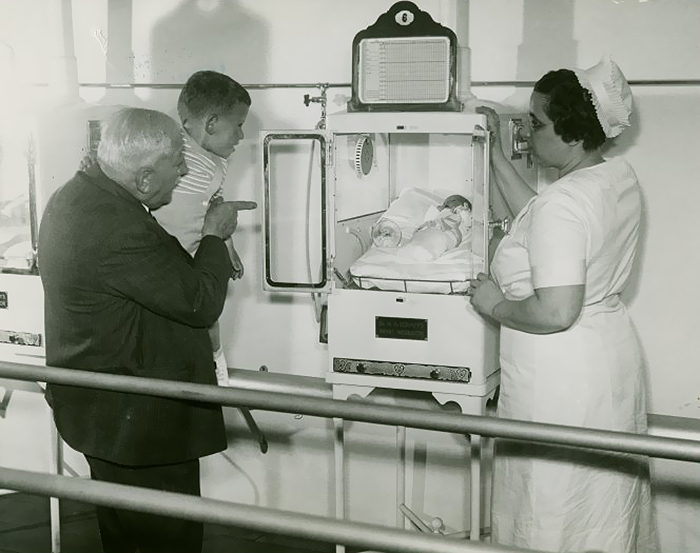

People speculate that Martin Couney might’ve not been an actual doctor

Image credits: New York Public Library

At the time of the sideshows, premature babies were generally considered genetically inferior and usually simply left to die. This was unacceptable for Martin Couney, so he came up with a solution that was as expensive as it was experimental. Modern problems require modern solutions, right? What set Couney’s sideshow apart from all the others that took place on Coney Island was that the subjects being shown off were premature babies in incubators, receiving care that no hospital could provide – this was never seen before. As such treatment was expensive – costing around $15 a day (an equivalent of more than $400 today) per incubator – people who paid 25 cents to see tiny babies were basically funding their fight for life.

Therefore, he was shunned by the medical world

Martin Couney was shunned by the medical professionals as a mere showman and not an actual doctor (his credentials turned out to be nonexistent), but he himself told the media that he’d give up on these exhibitions only when there’d be decent medical care for the prematurely born. The incubators themselves were a medical miracle – they were made of steel and glass and stood on legs that were about 5ft tall. Hot water was supplied by a boiler on the outside, to a bed of mesh on which the baby slept. The ‘physician’ was also an early advocate for breastfeeding and all of his nurses would be directly sacked if he caught them smoking or drinking. They wore starched white uniforms and the facility where babies were kept was always spotlessly clean.

Nonetheless, he helped to change the course of American medical history

Image credits: New York Public Library

People estimate that the Prussian-born showman saved the lives of somewhere around 6,500 infants and changed the course of American medical science. By the time of the early 1940s, the initial interest in premature babies’ sideshows had diminished, but hospitals started opening units dedicated to the care and treatment of premature babies. Couney’s dream had come true. Unfortunately, the pioneer for preemies care died in the 1950s at the age of 80 with no money in his pocket. But his legacy lives on.

Here’s how people online reacted

157Kviews

Share on FacebookI don't care whether Couney had a medical degree or not. The fact is that he took care of infants that had been disregarded and discarded by the medical community. His method of raising money may have been unconventional, (Think of today's GoFundMe and other types of begging) but it worked to fund the care of these babies. This man displayed actual humanity. The fact that he died poor, more than likely suggests that he didn't keep the money for himself. displayed actual humanity.

I have been a milk donor for preemies that was less then a kilo. So fragile and still so tough. I admire his work and his breastfeeding approach, he was a true hero, doctor or not.

Thank you for your kind help to other kids, and for the info Panda Kicki.

Load More Replies...I don't care whether Couney had a medical degree or not. The fact is that he took care of infants that had been disregarded and discarded by the medical community. His method of raising money may have been unconventional, (Think of today's GoFundMe and other types of begging) but it worked to fund the care of these babies. This man displayed actual humanity. The fact that he died poor, more than likely suggests that he didn't keep the money for himself. displayed actual humanity.

I have been a milk donor for preemies that was less then a kilo. So fragile and still so tough. I admire his work and his breastfeeding approach, he was a true hero, doctor or not.

Thank you for your kind help to other kids, and for the info Panda Kicki.

Load More Replies...

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

316

36