With millions of pictures taken every day, we can easily get lost in the vast world of images. That's why TIME magazine decided to create a list of the 100 most influential pictures ever taken. They teamed up with curators, historians, photo editors, and famous photographers around the world for this task. And now, you can find all of the most famous photos in one place, together with descriptions as to why these famous historical photos are such an important part of our legacy.

"No formula makes for iconic photos," the editors said. "Some rare historical photos are on our list because they were the first of their kind, others because they shaped the way we think. And some cut because they directly changed the way we live. What all of the 100 famous photos share is that they are turning points in our human experience."

The result they ended up with is not only a collection of superb historical photos but incredible human experiences as well. "The best photography is a form of bearing witness, a way of bringing a single vision to the larger world."

Ready to explore the world in a new view through the most famous photos of all time? If so, grab a cup of your favorite beverage and prepare for a journey that might just change the way you look at the world. The photo gallery of the most famous pictures of our age is right at your fingertips!

More info: time.com

This post may include affiliate links.

The Terror Of War, Nick Ut, 1972

The faces of collateral damage and friendly fire are generally not seen. This was not the case with 9-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc. On June 8, 1972, Associated Press photographer Nick Ut was outside Trang Bang, about 25 miles northwest of Saigon, when the South Vietnamese air force mistakenly dropped a load of napalm on the village. As the Vietnamese photographer took pictures of the carnage, he saw a group of children and soldiers along with a screaming naked girl running up the highway toward him. Ut wondered, Why doesn’t she have clothes? He then realized that she had been hit by napalm. “I took a lot of water and poured it on her body. She was screaming, ‘Too hot! Too hot!’” Ut took Kim Phuc to a hospital, where he learned that she might not survive the third-degree burns covering 30 percent of her body. So with the help of colleagues he got her transferred to an American facility for treatment that saved her life. Ut’s photo of the raw impact of conflict underscored that the war was doing more harm than good. It also sparked newsroom debates about running a photo with nudity, pushing many publications, including the New York Times, to override their policies. The photo quickly became a cultural shorthand for the atrocities of the Vietnam War and joined Malcolm Browne’s Burning Monk and Eddie Adams’ Saigon Execution as defining images of that brutal conflict. When President Richard Nixon wondered if the photo was fake, Ut commented, “The horror of the Vietnam War recorded by me did not have to be fixed.” In 1973 the Pulitzer committee agreed and awarded him its prize. That same year, America’s involvement in the war ended.

Years later Kim was removed while studying medicine from her university. She was used as a propaganda symbol by the communist government of Vietnam. In 1986, , she continued her studies in Cuba. In Cuba, she met Bui Huy Toan, another Vietnamese student and her future fiancé. In 1992 they married, and went on their honeymoon in Moscow. During a refuelling stop in Newfoundland, they left the plane and asked for political asylum in Canada, which was granted. The couple now live in Ajax, Ontario, and have two children. In 1996, Phúc met the surgeons who had saved her life. The following year, she passed the Canadian Citizenship Test with a perfect score and became a Canadian citizen. In 1997 she established the first Kim Phúc Foundation in the U.S., with the aim of providing medical and psychological assistance to child victims of war

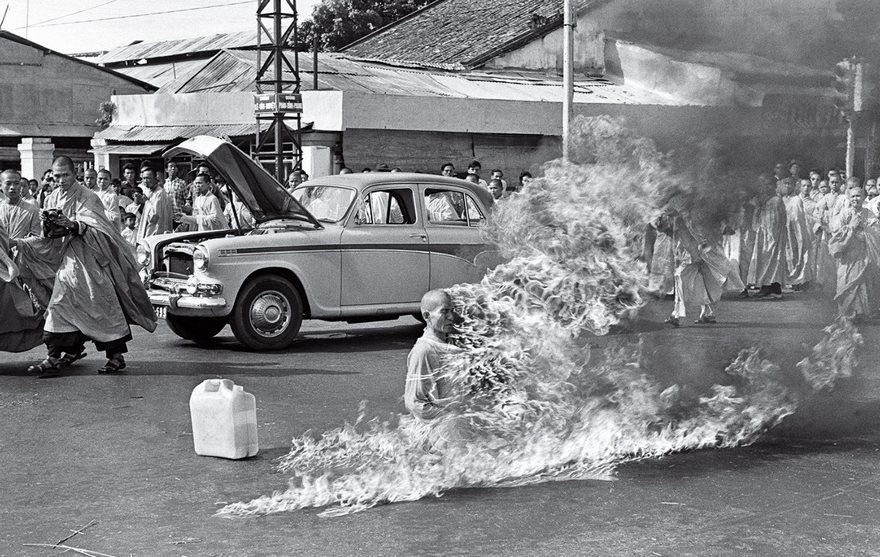

The Burning Monk, Malcolm Browne, 1963

In June 1963, most Americans couldn’t find Vietnam on a map. But there was no forgetting that war-torn Southeast Asian nation after Associated Press photographer Malcolm Browne captured the image of Thich Quang Duc immolating himself on a Saigon street. Browne had been given a heads-up that something was going to happen to protest the treatment of Buddhists by the regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem. Once there he watched as two monks doused the seated elderly man with gasoline. “I realized at that moment exactly what was happening, and began to take pictures a few seconds apart,” he wrote soon after. His Pulitzer Prize–winning photo of the seemingly serene monk sitting lotus style as he is enveloped in flames became the first iconic image to emerge from a quagmire that would soon pull in America. Quang Duc’s act of martyrdom became a sign of the volatility of his nation, and President Kennedy later commented, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.” Browne’s photo forced people to question the U.S.’s association with Diem’s government, and soon resulted in the Administration’s decision not to interfere with a coup that November.

Starving Child And Vulture, Kevin Carter, 1993

Kevin Carter knew the stench of death. As a member of the Bang-Bang Club, a quartet of brave photographers who chronicled apartheid-era South Africa, he had seen more than his share of heartbreak. In 1993 he flew to Sudan to photograph the famine racking that land. Exhausted after a day of taking pictures in the village of Ayod, he headed out into the open bush. There he heard whimpering and came across an emaciated toddler who had collapsed on the way to a feeding center. As he took the child’s picture, a plump vulture landed nearby. Carter had reportedly been advised not to touch the victims because of disease, so instead of helping, he spent 20 minutes waiting in the hope that the stalking bird would open its wings. It did not. Carter scared the creature away and watched as the child continued toward the center. He then lit a cigarette, talked to God and wept. The New York Times ran the photo, and readers were eager to find out what happened to the child—and to criticize Carter for not coming to his subject’s aid. His image quickly became a wrenching case study in the debate over when photographers should intervene. Subsequent research seemed to reveal that the child did survive yet died 14 years later from malarial fever. Carter won a Pulitzer for his image, but the darkness of that bright day never lifted from him. In July 1994 he took his own life, writing, “I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain.”

I shall always remember this little boy, and his photographer. When my own burdens become heavy, this will be a good reminder that my own plight is nothing compared to what these two endured.

What Makes an Amazing Photo?

You might’ve noticed that the photos you snap with your phone rarely come out looking as good as these famous photos in history you can see on our list. And you might’ve wondered why that is so and what exactly you need for a photo to be iconic or at least amazing.

Here’s the lowdown - there are many elements that have to fall into place for the absolute perfect picture, such as:

- Lighting;

- The rule of thirds (it’s a composition guideline that places your subject in the left or right third of the image, leaving the other two thirds more open);

- Lines;

- Shapes;

- Textures;

- Patterns;

- Colors;

- And most importantly - substance and meaning behind your shot.

Seems like a lot, right? Well, to be perfectly honest, not all rules must apply to one single photo, and the variations between these essential elements are limitless. But that’s what makes photography so interesting and fun to try!

As for these famous historical photos on our list, they are so awesome mainly because they are absolutely unique images that capture some of the most important events in our history.

Lunch Atop A Skyscraper, 1932

It’s the most perilous yet playful lunch break ever captured: 11 men casually eating, chatting and sneaking a smoke as if they weren’t 840 feet above Manhattan with nothing but a thin beam keeping them aloft. That comfort is real; the men are among the construction workers who helped build Rockefeller Center. But the picture, taken on the 69th floor of the flagship RCA Building (now the GE Building), was staged as part of a promotional campaign for the massive skyscraper complex. While the photographer and the identities of most of the subjects remain a mystery—the photographers Charles C. Ebbets, Thomas Kelley and William Leftwich were all present that day, and it’s not known which one took it—there isn’t an ironworker in New York City who doesn’t see the picture as a badge of their bold tribe. In that way they are not alone. By thumbing its nose at both danger and the Depression, Lunch Atop a Skyscraper came to symbolize American resilience and ambition at a time when both were desperately needed. It has since become an iconic emblem of the city in which it was taken, affirming the romantic belief that New York is a place unafraid to tackle projects that would cow less brazen cities. And like all symbols in a city built on hustle, Lunch Atop a Skyscraper has spawned its own economy. It is the Corbis photo agency’s most reproduced image. And good luck walking through Times Square without someone hawking it on a mug, magnet or T-shirt.

Interesting at how much of an impact this photo made during it's heyday.... and almost a hundred years later, people don't have the understanding of what it represented.

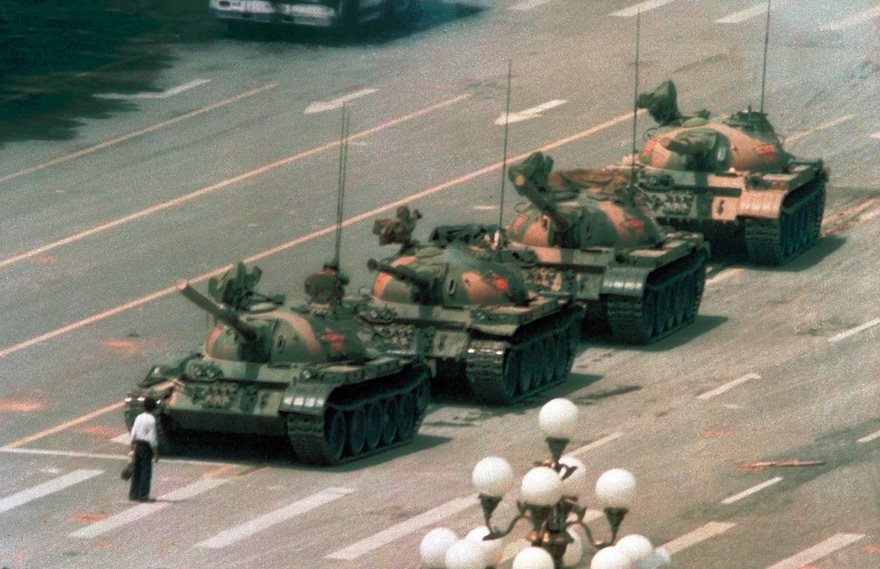

Tank Man, Jeff Widener, 1989

On the morning of June 5, 1989, photographer Jeff Widener was perched on a sixth-floor balcony of the Beijing Hotel. It was a day after the Tiananmen Square massacre, when Chinese troops attacked pro-democracy demonstrators camped on the plaza, and the Associated Press sent Widener to document the aftermath. As he photographed bloody victims, passersby on bicycles and the occasional scorched bus, a column of tanks began rolling out of the plaza. Widener lined up his lens just as a man carrying shopping bags stepped in front of the war machines, waving his arms and refusing to move.

The tanks tried to go around the man, but he stepped back into their path, climbing atop one briefly. Widener assumed the man would be killed, but the tanks held their fire. Eventually the man was whisked away, but not before Widener immortalized his singular act of resistance. Others also captured the scene, but Widener’s image was transmitted over the AP wire and appeared on front pages all over the world. Decades after Tank Man became a global hero, he remains unidentified. The anonymity makes the photograph all the more universal, a symbol of resistance to unjust regimes everywhere.

Actually while others did both record and photograph the event, officials saw them and came around the hotel gather an destroying films, the photographer saw them pointing and quickly went inside and hide some of his film (including photos and videos) in the top part of the hotel toilet

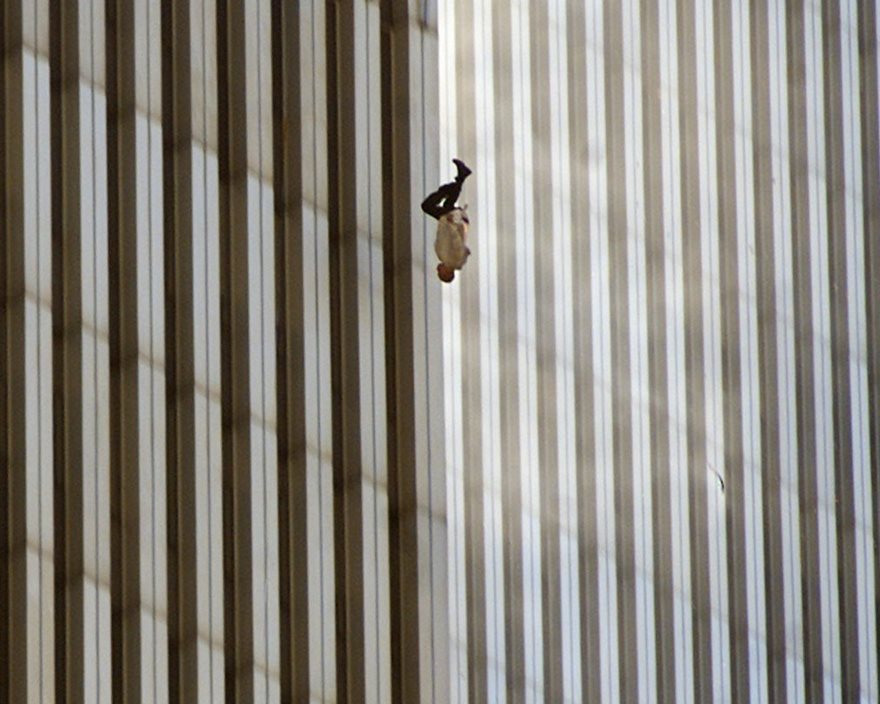

Falling Man, Richard Drew, 2001

The most widely seen images from 9/11 are of planes and towers, not people. Falling Man is different. The photo, taken by Richard Drew in the moments after the September 11, 2001, attacks, is one man’s distinct escape from the collapsing buildings, a symbol of individuality against the backdrop of faceless skyscrapers. On a day of mass tragedy, Falling Man is one of the only widely seen pictures that shows someone dying. The photo was published in newspapers around the U.S. in the days after the attacks, but backlash from readers forced it into temporary obscurity. It can be a difficult image to process, the man perfectly bisecting the iconic towers as he darts toward the earth like an arrow. Falling Man’s identity is still unknown, but he is believed to have been an employee at the Windows on the World restaurant, which sat atop the north tower. The true power of Falling Man, however, is less about who its subject was and more about what he became: a makeshift Unknown Soldier in an often unknown and uncertain war, suspended forever in history.

I saw him and many others fall to their deaths trying to escape the flames live on national news, while I held my infant daughter in my arms and wept, the nightmares haunted me for years the images bring tears to my eyes to this very day. I will never forget.

What is the most Famous Photograph of all Time?

With so many iconic photos, it is only natural to be curious to know which one of them is the most famous or the most-seen images of all time. Is it one of Annie Leibovitz famous photos? Or maybe the one with a sailor kissing a maid in Times Square? Could it be one of those famous black-and-white photos from photography’s early days?

To provide you with a clear answer, we have to divide this question into two parts - the most famous photo and the most seen one. The title of the most famous photo would then go to Henri Cartier-Bresson's iconic image capturing a man jumping the puddle from 1932 - you can find it on our list!

When it comes to the most-seen image of all time, you might be surprised to learn that you’ve also stared at it countless times without even thinking about it! Yes, it’s the iconic Windows screensaver with rolling green hills in Sonoma County, California, by Charles O’Rear. It is estimated that this photo has been seen by more than a billion people since it emerged in 2002.

That said, there are plenty more images that shaped our history and our culture, and you’re sure to find them on our list. From famous Vietnam war photos documenting the brutal nature of humankind to famous crime scene photos that showed the dirty underbelly of our society to much more elevated topics and images such as space exploration and scientific achievements that saved millions of lives. Yes, you are right - these most famous photos of all time are as diverse as our history because they are a part of it!

Alan Kurdi, Nilüfer Demir, 2015

The war in Syria had been going on for more than four years when Alan Kurdi’s parents lifted the 3-year-old boy and his 5-year-old brother into an inflatable boat and set off from the Turkish coast for the Greek island of Kos, just three miles away. Within minutes of pushing off, a wave capsized the vessel, and the mother and both sons drowned. On the shore near the coastal town of Bodrum a few hours later, Nilufer Demir of the Dogan News Agency, came upon Alan, his face turned to one side and bottom elevated as if he were just asleep. “There was nothing left to do for him. There was nothing left to bring him back to life,” she said. So Demir raised her camera. "I thought, This is the only way I can express the scream of his silent body."

The resulting image became the defining photograph of an ongoing war that, by the time Demir pressed her shutter, had killed some 220,000 people. It was taken not in Syria, a country the world preferred to ignore, but on the doorstep of Europe, where its refugees were heading. Dressed for travel, the child lay between one world and another: waves had washed away any chalky brown dust that might locate him in a place foreign to Westerners’ experience. It was an experience the Kurdis sought for themselves, joining a migration fueled as much by aspiration as desperation. The family had already escaped bloodshed by making it across the land border to Turkey; the sea journey was in search of a better life, one that would now become — at least for a few months — far more accessible for the hundreds of thousands traveling behind them.

Demir’s image whipped around social media within hours, accumulating potency with every share. News organizations were compelled to publish it—or publicly defend their decision not to. And European governments were suddenly compelled to open closed frontiers. Within a week, trainloads of Syrians were arriving in Germany to cheers, as a war lamented but not felt suddenly brimmed with emotions unlocked by a picture of one small, still form.

Please let me correct the description. The boy died 02.09, the first trains full with refugees arrived in Germany before the picture was shown in media. Germany opened the borders before this very sad picture was published. But yes, it is very sad, that so many european countries still not open their borders and few countries have to carry the "burden" alone. This picture made me cry at work (and I am a man), because he remembers me of my own son of the same age. Too many children suffer during all this useless wars which only give few men money and power but destroy thousands and millions of lives.

Earthrise, William Anders, NASA, 1968

It’s never easy to identify the moment a hinge turns in history. When it comes to humanity’s first true grasp of the beauty, fragility and loneliness of our world, however, we know the precise instant. It was on December 24, 1968, exactly 75 hours, 48 minutes and 41 seconds after the Apollo 8 spacecraft lifted off from Cape Canaveral en route to becoming the first manned mission to orbit the moon. Astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders entered lunar orbit on Christmas Eve of what had been a bloody, war-torn year for America. At the beginning of the fourth of 10 orbits, their spacecraft was emerging from the far side of the moon when a view of the blue-white planet filled one of the hatch windows. “Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Anders exclaimed. He snapped a picture—in black and white. Lovell scrambled to find a color canister. “Well, I think we missed it,” Anders said. Lovell looked through windows three and four. “Hey, I got it right here!” he exclaimed. A weightless Anders shot to where Lovell was floating and fired his Hasselblad. “You got it?” Lovell asked. “Yep,” Anders answered. The image—our first full-color view of our planet from off of it—helped to launch the environmental movement. And, just as important, it helped human beings recognize that in a cold and punishing cosmos, we’ve got it pretty good.

love this photo. every single living thing we've ever known, minus the astronauts, all in this one shot.

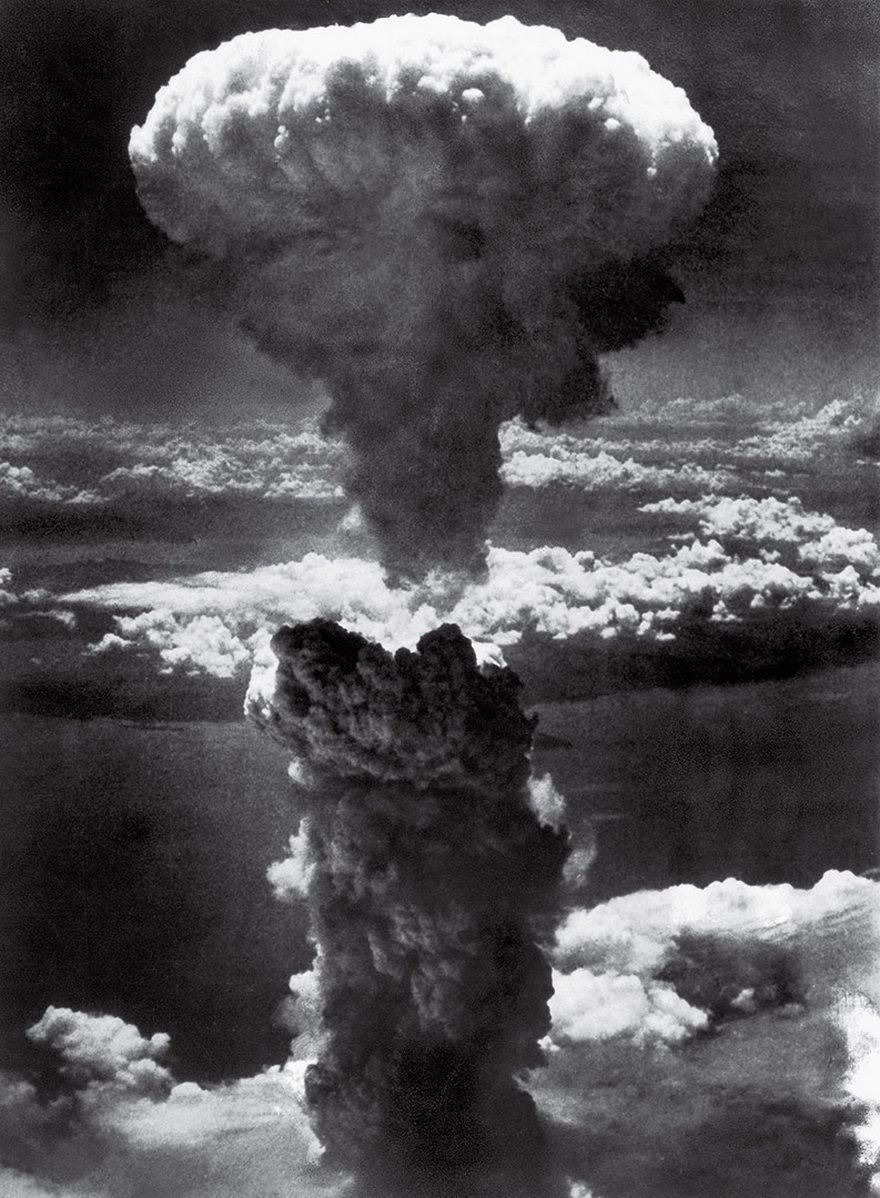

Mushroom Cloud Over Nagasaki, Lieutenant Charles Levy, 1945

Three days after an atomic bomb nicknamed Little Boy obliterated Hiroshima, Japan, U.S. forces dropped an even more powerful weapon dubbed Fat Man on Nagasaki. The explosion shot up a 45,000-foot-high column of radioactive dust and debris. “We saw this big plume climbing up, up into the sky,” recalled Lieutenant Charles Levy, the bombardier, who was knocked over by the blow from the 20-kiloton weapon. “It was purple, red, white, all colors—something like boiling coffee. It looked alive.” The officer then shot 16 photographs of the new weapon’s awful power as it yanked the life out of some 80,000 people in the city on the Urakami River. Six days later, the two bombs forced Emperor Hirohito to announce Japan’s unconditional surrender in World War II. Officials censored photos of the bomb’s devastation, but Levy’s image—the only one to show the full scale of the mushroom cloud from the air—was circulated widely. The effect shaped American opinion in favor of the nuclear bomb, leading the nation to celebrate the atomic age and proving, yet again, that history is written by the victors.

I cannot even imagine a 45,000-foot-high column. This goes back to the saying that there are no winners in war.

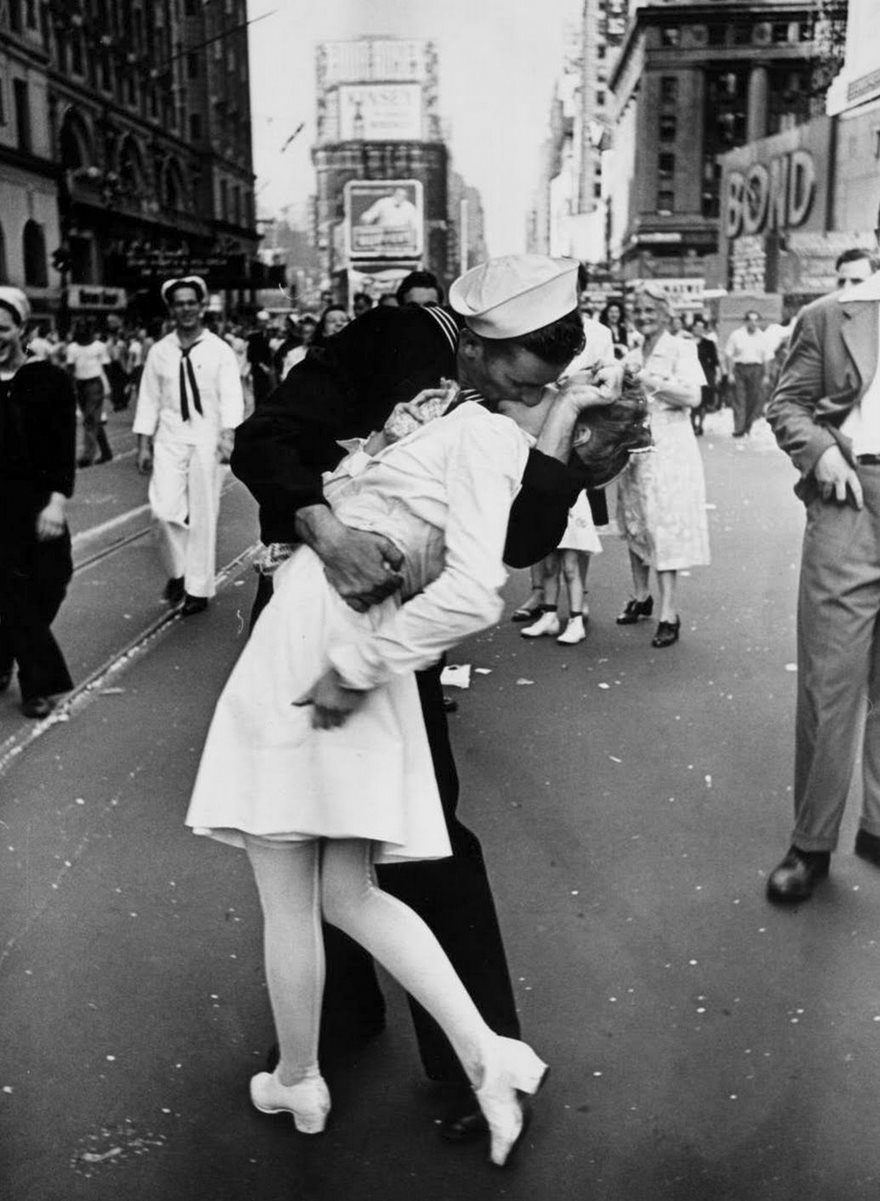

V-J Day In Times Square, Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1945

At its best, photography captures fleeting snippets that crystallize the hope, anguish, wonder and joy of life. Alfred Eisenstaedt, one of the first four photographers hired by LIFE magazine, made it his mission “to find and catch the storytelling moment.” He didn’t have to go far for it when World War II ended on August 14, 1945. Taking in the mood on the streets of New York City, Eisenstaedt soon found himself in the joyous tumult of Times Square. As he searched for subjects, a sailor in front of him grabbed hold of a nurse, tilted her back and kissed her. Eisenstaedt’s photograph of that passionate swoop distilled the relief and promise of that momentous day in a single moment of unbridled joy (although some argue today that it should be seen as a case of sexual assault). His beautiful image has become the most famous and frequently reproduced picture of the 20th century, and it forms the basis of our collective memory of that transformative moment in world history. “People tell me that when I’m in heaven,” Eisenstaedt said, “they will remember this picture.”

well...it IS sexual assault... I always thought these two were a couple, but now that I know the truth this picture lost its shine to me. I seriously hope that she took it well and thought of it as funny, or else this pic is really messed up.

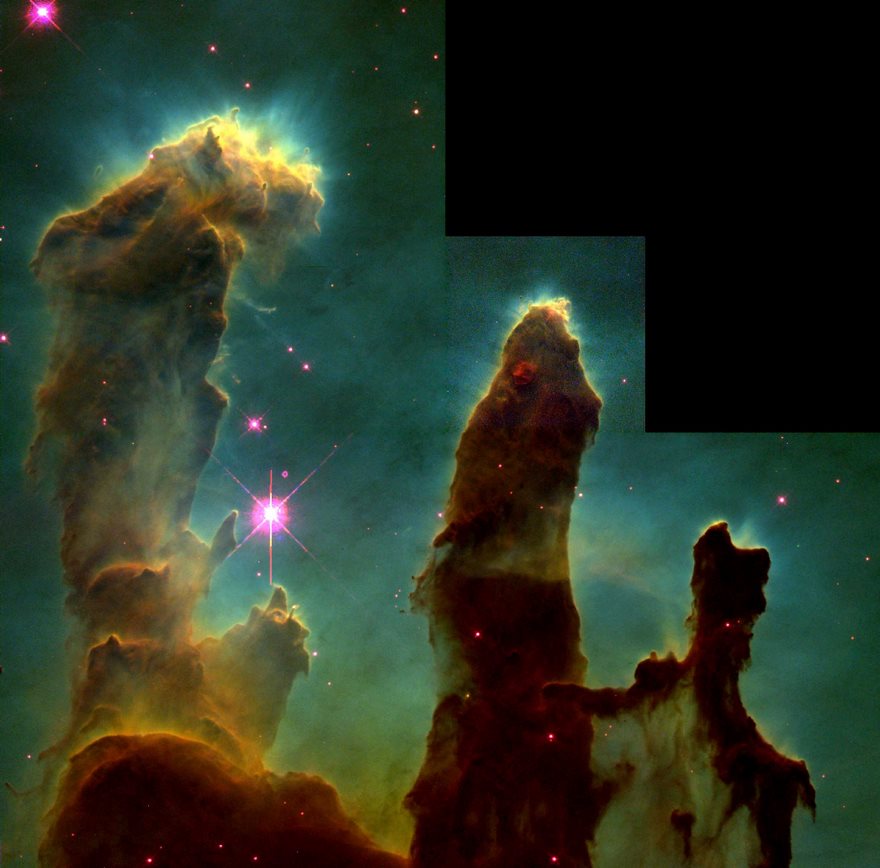

Pillars Of Creation, Nasa, 1995

The Hubble Space Telescope almost didn’t make it. Carried aloft in 1990 aboard the space shuttle Atlantis, it was over-budget, years behind schedule and, when it finally reached orbit, nearsighted, its 8-foot mirror distorted as a result of a manufacturing flaw. It would not be until 1993 that a repair mission would bring Hubble online. Finally, on April 1, 1995, the telescope delivered the goods, capturing an image of the universe so clear and deep that it has come to be known as Pillars of Creation. What Hubble photographed is the Eagle Nebula, a star-forming patch of space 6,500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Serpens Cauda. The great smokestacks are vast clouds of interstellar dust, shaped by the high-energy winds blowing out from nearby stars (the black portion in the top right is from the magnification of one of Hubble’s four cameras). But the science of the pillars has been the lesser part of their significance. Both the oddness and the enormousness of the formation—the pillars are 5 light-years, or 30 trillion miles, long—awed, thrilled and humbled in equal measure. One image achieved what a thousand astronomy symposia never could.

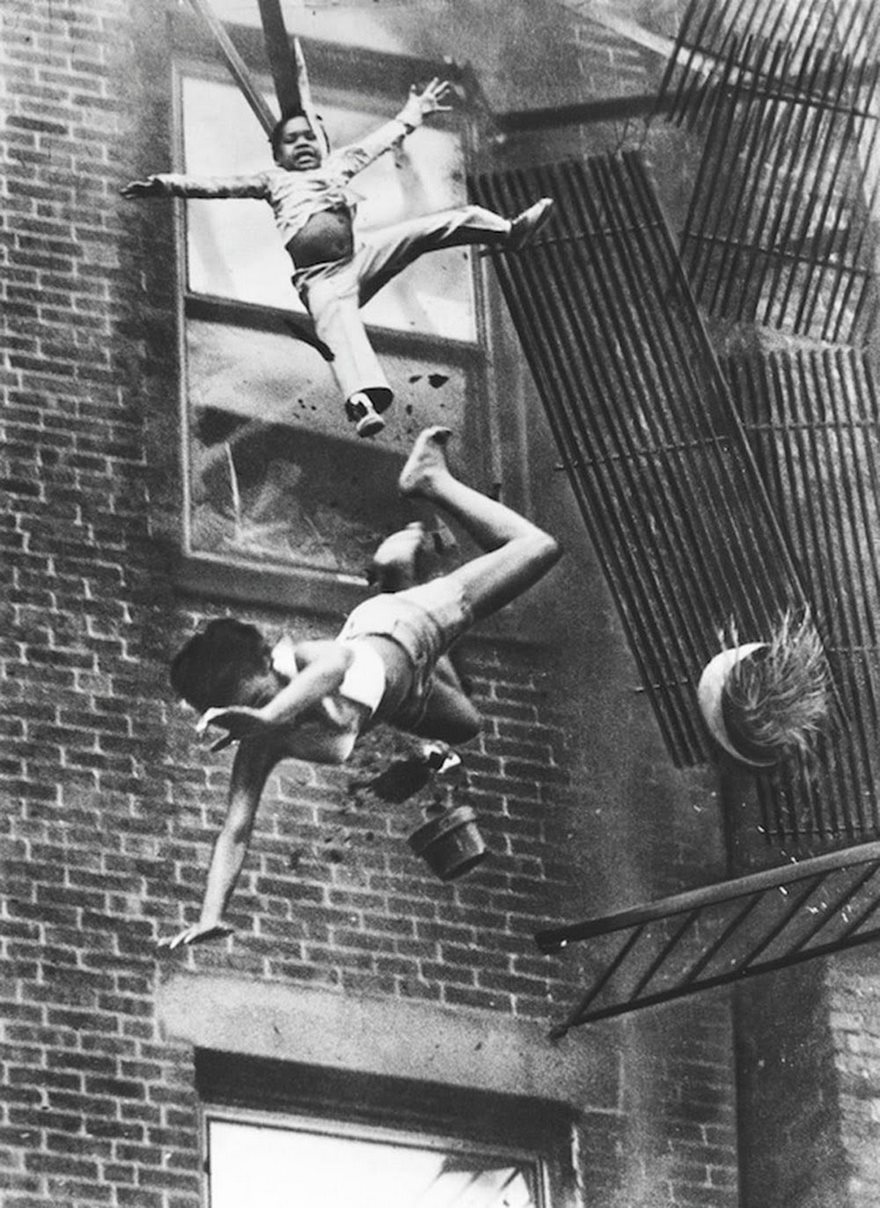

Fire Escape Collapse, Stanley Forman, 1975

Stanley Forman was working for the Boston Herald American on July 22, 1975, when he got a call about a fire on Marlborough Street. He raced over in time to see a woman and child on a fifth-floor fire escape. A fireman had set out to help them, and Forman figured he was shooting another routine rescue. “Suddenly the fire escape gave way,” he recalled, and Diana Bryant, 19, and her goddaughter Tiare Jones, 2, were swimming through the air. “I was shooting pictures as they were falling—then I turned away. It dawned on me what was happening, and I didn’t want to see them hit the ground. I can still remember turning around and shaking.” Bryant died from the fall, her body cushioning the blow for her goddaughter, who survived. While the event was no different from the routine tragedies that fill the local news, Forman’s picture of it was. Using a motor-drive camera, Forman was able to freeze the horrible tumbling moment down to the expression on young Tiare’s face. The photo earned Forman the Pulitzer Prize and led municipalities around the country to enact tougher fire-escape-safety codes. But its lasting legacy is as much ethical as temporal. Many readers objected to the publication of Forman’s picture, and it remains a case study in the debate over when disturbing images are worth sharing.

Disturbing pictures are always worth sharing when the impact seen is so severe, that it evokes a change in society.

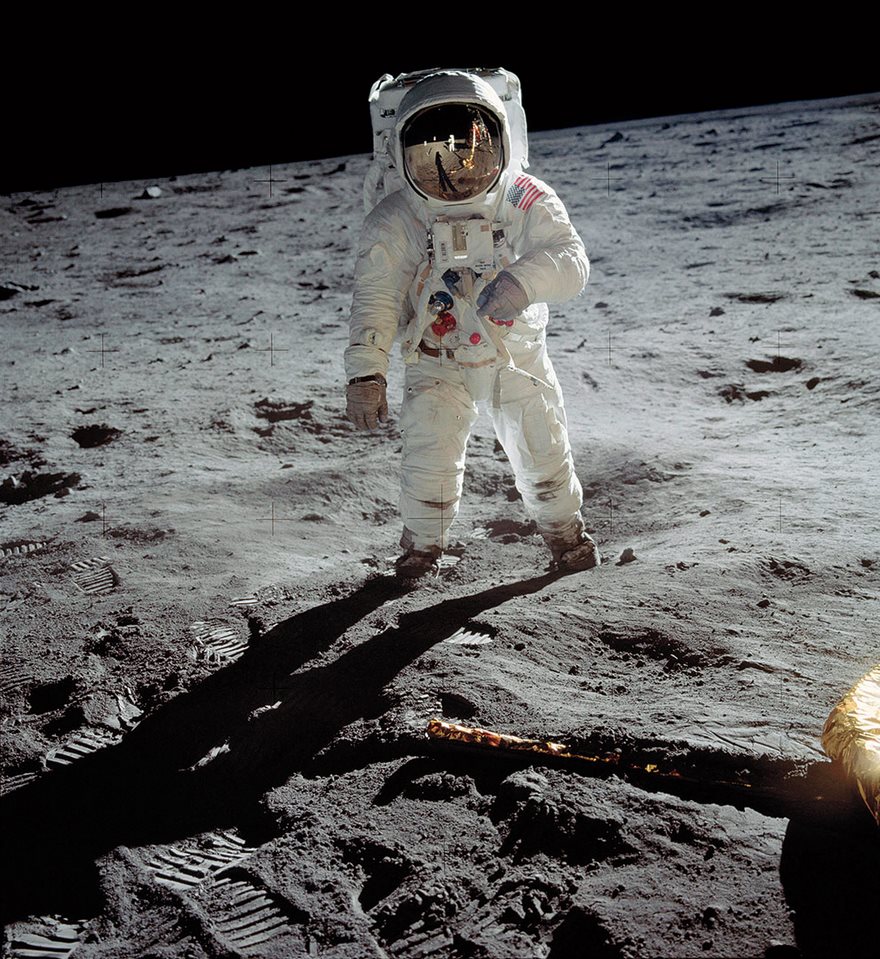

A Man On The Moon, Neil Armstrong, Nasa, 1969

Somewhere in the Sea of Tranquillity, the little depression in which Buzz Aldrin stood on the evening of July 20, 1969, is still there—one of billions of pits and craters and pockmarks on the moon’s ancient surface. But it may not be the astronaut’s most indelible mark.

Aldrin never cared for being the second man on the moon—to come so far and miss the epochal first-man designation Neil Armstrong earned by a mere matter of inches and minutes. But Aldrin earned a different kind of immortality. Since it was Armstrong who was carrying the crew’s 70-millimeter Hasselblad, he took all of the pictures—meaning the only moon man earthlings would see clearly would be the one who took the second steps. That this image endured the way it has was not likely. It has none of the action of the shots of Aldrin climbing down the ladder of the lunar module, none of the patriotic resonance of his saluting the American flag. He’s just standing in place, a small, fragile man on a distant world—a world that would be happy to kill him if he removed so much as a single article of his exceedingly complex clothing. His arm is bent awkwardly—perhaps, he has speculated, because he was glancing at the checklist on his wrist. And Armstrong, looking even smaller and more spectral, is reflected in his visor. It’s a picture that in some ways did everything wrong if it was striving for heroism. As a result, it did everything right.

Albino Boy, Biafra, Don Mccullin, 1969

Few remember Biafra, the tiny western African nation that split off from southern Nigeria in 1967 and was retaken less than three years later. Much of the world learned of the enormity of that brief struggle through images of the mass starvation and disease that took the lives of possibly millions. None proved as powerful as British war photographer Don McCullin’s picture of a 9-year-old albino child. “To be a starving Biafran orphan was to be in a most pitiable situation, but to be a starving albino Biafran was to be in a position beyond description,” McCullin wrote. “Dying of starvation, he was still among his peers an object of ostracism, ridicule and insult.” This photo profoundly influenced public opinion, pressured governments to take action, and led to massive airlifts of food, medicine and weapons. McCullin hoped that such stark images would be able to “break the hearts and spirits of secure people.” While public attention eventually shifted, McCullin’s work left a lasting legacy: he and other witnesses of the conflict inspired the launch of Doctors Without Borders, which delivers emergency medical support to those suffering from war, epidemics and disasters.

God bless Doctors Without Borders and the many other organizations who do so much to help those with so little

Jewish Boy Surrenders In Warsaw, 1943

The terrified young boy with his hands raised at the center of this image was one of nearly half a million Jews packed into the Warsaw ghetto, a neighborhood transformed by the Nazis into a walled compound of grinding starvation and death. Beginning in July 1942, the German occupiers started shipping some 5,000 Warsaw inhabitants a day to concentration camps. As news of exterminations seeped back, the ghetto’s residents formed a resistance group. “We saw ourselves as a Jewish underground whose fate was a tragic one,” wrote its young leader Mordecai Anielewicz. “For our hour had come without any sign of hope or rescue.” That hour arrived on April 19, 1943, when Nazi troops came to take the rest of the Jews away. The sparsely armed partisans fought back but were eventually subdued by German tanks and flamethrowers. When the revolt ended on May 16, the 56,000 survivors faced summary execution or deportation to concentration and slave-labor camps. SS Major General Jürgen Stroop took such pride in his work clearing out the ghetto that he created the Stroop Report, a leather-bound victory album whose 75 pages include a laundry list of boastful spoils, reports of daily killings and dozens of heart-wrenching photos like that of the boy raising his hands. This collection proved his undoing, for besides giving a face to those who died, the pictures reveal the power of photography as a documentary tool. At the subsequent Nuremburg war-crimes trials, the volume became key evidence against Stroop and resulted in his hanging near the ghetto in 1951. The Holocaust produced scores of searing images. But none had the evidentiary impact of the boy’s surrender. The child, whose identity has never been confirmed, has come to represent the face of the 6 million defenseless Jews killed by the Nazis.

Bloody Saturday, H.s. Wong, 1937

The same imperialistic desires festering in Europe in the 1930s had already swept into Asia. Yet many Americans remained wary of wading into a conflict in what seemed a far-off, alien land. But that opinion began to change as Japan’s army of the Rising Sun rolled toward Shanghai in the summer of 1937. Fighting started there in August, and the unrelenting shelling and bombing caused mass panic and death in the streets. But the rest of the world didn’t put a face to the victims until they saw the aftermath of an August 28 attack by Japanese bombers. When H.S. Wong, a photographer for Hearst Metrotone News nicknamed Newsreel, arrived at the destroyed South Station, he recalled carnage so fresh “that my shoes were soaked with blood.” In the midst of the devastation, Wong saw a wailing Chinese baby whose mother lay dead on nearby tracks. He said he quickly shot his remaining film and then ran to carry the baby to safety, but not before the boy’s father raced over and ferried him away. Wong’s image of the wounded, helpless infant was sent to New York and featured in Hearst newsreels, newspapers and life magazine—the widest audience a picture could then have. Viewed by more than 136 million people, it struck a personal chord that transcended ethnicity and geography. To many, the infant’s pain represented the plight of China and the bloodlust of Japan, and the photo dubbed Bloody Saturday was transformed into one of the most powerful news pictures of all time. Its dissemination reveals the potent force of an image to sway official and public opinion. Wong’s picture led the U.S., Britain and France to formally protest the attack and helped shift Western sentiment in favor of wading into what would become the world’s second great war.

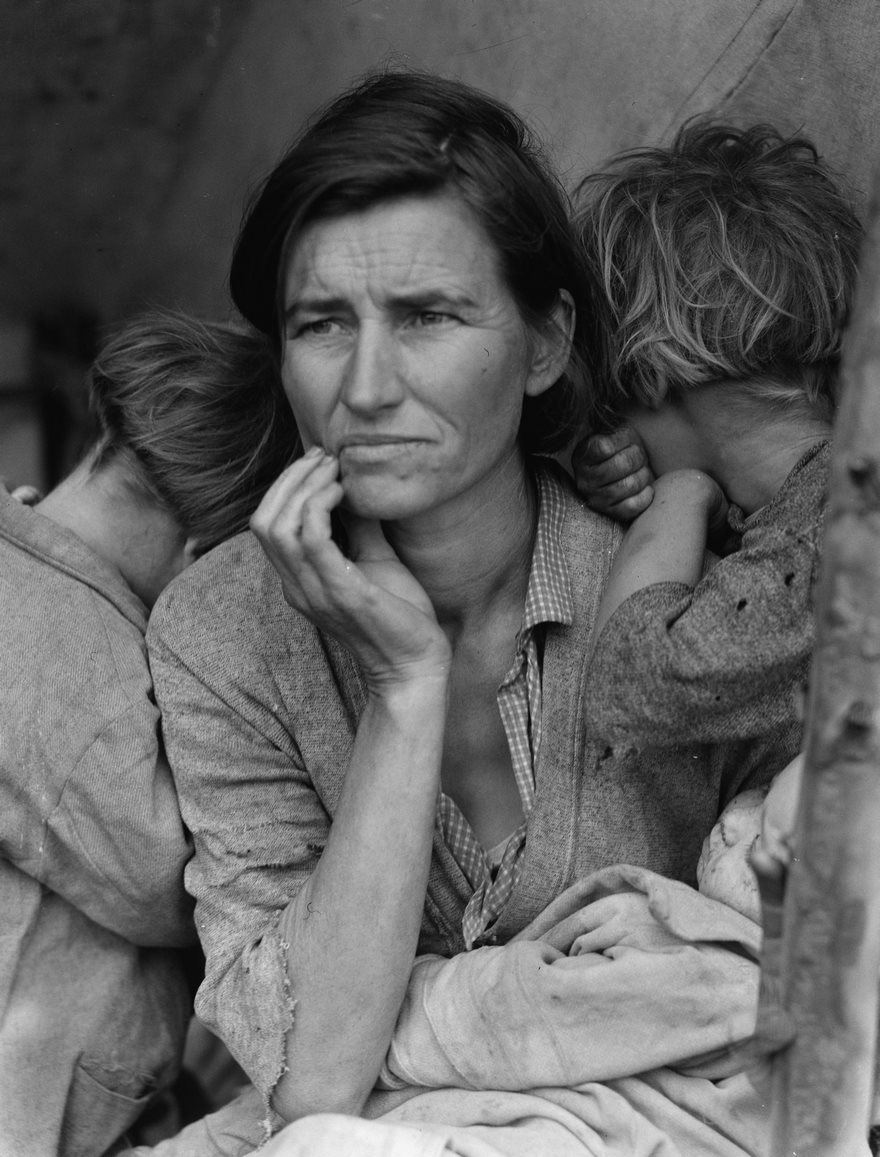

Migrant Mother, Dorothea Lange, 1936

The picture that did more than any other to humanize the cost of the Great Depression almost didn’t happen. Driving past the crude “Pea-Pickers Camp” sign in Nipomo, north of Los Angeles, Dorothea Lange kept going for 20 miles. But something nagged at the photographer from the government’s Resettlement Administration, and she finally turned around. At the camp, the Hoboken, N.J.–born Lange spotted Frances Owens Thompson and knew she was in the right place. “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother in the sparse lean-to tent, as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange later wrote. The farm’s crop had frozen, and there was no work for the homeless pickers, so the 32-year-old Thompson sold the tires from her car to buy food, which was supplemented with birds killed by the children. Lange, who believed that one could understand others through close study, tightly framed the children and the mother, whose eyes, worn from worry and resignation, look past the camera. Lange took six photos with her 4x5 Graflex camera, later writing, “I knew I had recorded the essence of my assignment.” Afterward Lange informed the authorities of the plight of those at the encampment, and they sent 20,000 pounds of food. Of the 160,000 images taken by Lange and other photographers for the Resettlement Administration, Migrant Mother has become the most iconic picture of the Depression. Through an intimate portrait of the toll being exacted across the land, Lange gave a face to a suffering nation.

I'm going to get a lot of criticism for posting this, but I'm going to do it anyway. Firstly her name was Florence not Frances. This photo served a fantastic purpose to show just how hard lives were and went a long way towards ending suffering. These people received much needed food because of this photo. I'm very glad the photo was taken...but it was staged and part of the story was a lie. Florence was at the camp because her car had broken down and not to sell her tyres. She worked with the photographer to create that pensive look and the photo was edited to remove the photographer's hand as she held open the tent flap. She also lied to Florence telling her the photos would never be published. She earned fame while Florence received nothing. It's a shame because Florence's real story is more interesting and emotional than the made up one. You can read it here https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Owens_Thompson So iconic yes, truthful no. But I'm so grateful it was taken

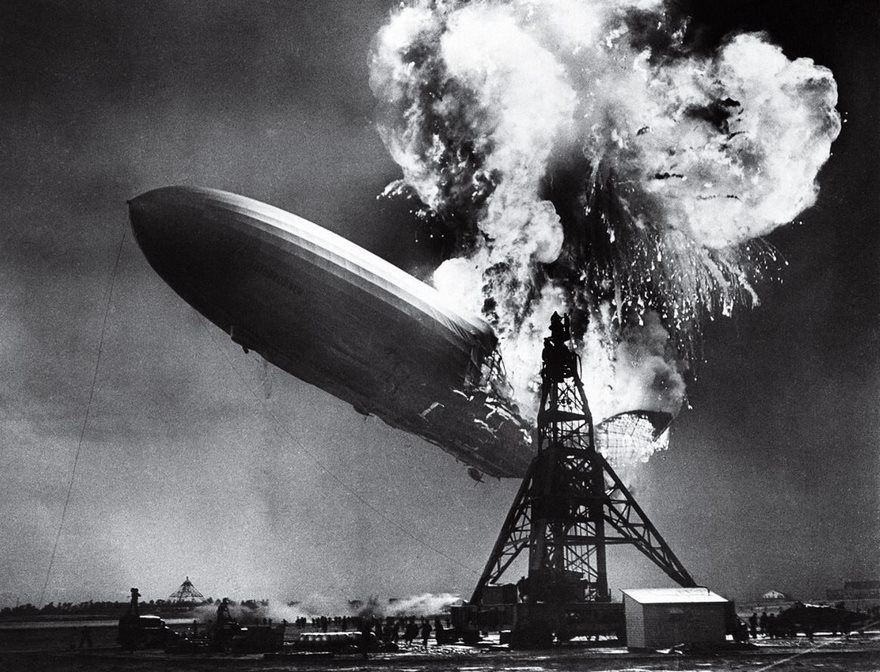

The Hindenburg Disaster, Sam Shere, 1937

Zeppelins were majestic skyliners, luxurious behemoths that signified wealth and power. The arrival of these ships was news, which is why Sam Shere of the International News Photos service was waiting in the rain at the Lakehurst, N.J., Naval Air Station on May 6, 1937, for the 804-foot-long LZ 129 Hindenburg to drift in from Frankfurt. Suddenly, as the assembled media watched, the grand ship’s flammable hydrogen caught fire, causing it to spectacularly burst into bright yellow flames and kill 36 people. Shere was one of nearly two dozen still and newsreel photographers who scrambled to document the fast-moving tragedy. But it is his image, with its stark immediacy and horrible grandeur, that has endured as the most famous—owing to its publication on front pages around the world and in LIFE and, more than three decades later, its use on the cover of the first Led Zeppelin album. The crash helped bring the age of the airships to a close, and Shere’s powerful photograph of one of the world’s most formative early air disasters persists as a cautionary reminder of how human fallibility can lead to death and destruction. Almost as famous as Shere’s photo is the anguished voice of Chicago radio announcer Herbert Morrison, who cried as he watched people tumbling through the air, “It is bursting into flames ... This is terrible. This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world ... Oh, the humanity!”

This photo was taken by Daily News photographer, Charles Hoff. Not Sam Shere. Charles Hoff is my grandfather so I know the image well. http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265376

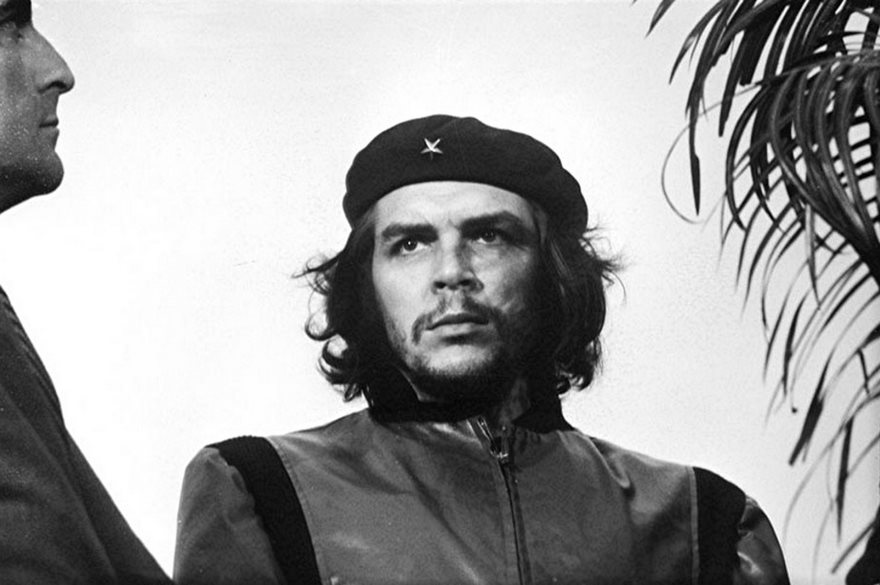

Guerillero Heroico, Alberto Korda, 1960

The day before Alberto Korda took his iconic photograph of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, a ship had exploded in Havana Harbor, killing the crew and dozens of dockworkers. Covering the funeral for the newspaper Revolución, Korda focused on Fidel Castro, who in a fiery oration accused the U.S. of causing the explosion. The two frames he shot of Castro’s young ally were a seeming afterthought, and they went unpublished by the newspaper. But after Guevara was killed leading a guerrilla movement in Bolivia nearly seven years later, the Cuban regime embraced him as a martyr for the movement, and Korda’s image of the beret-clad revolutionary soon became its most enduring symbol. In short order, Guerrillero Heroico was appropriated by artists, causes and admen around the world, appearing on everything from protest art to underwear to soft drinks. It has become the cultural shorthand for rebellion and one of the most recognizable and reproduced images of all time, with its influence long since transcending its steely-eyed subject.

Dalí Atomicus, Philippe Halsman, 1948

Capturing the essence of those he photographed was Philippe Halsman’s life’s work. So when Halsman set out to shoot his friend and longtime collaborator the Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, he knew a simple seated portrait would not suffice. Inspired by Dalí’s painting Leda Atomica, Halsman created an elaborate scene to surround the artist that included the original work, a floating chair and an in-progress easel suspended by thin wires. Assistants, including Halsman’s wife and young daughter Irene, stood out of the frame and, on the photographer’s count, threw three cats and a bucket of water into the air while Dalí leaped up. It took the assembled cast 26 takes to capture a composition that satisfied Halsman. And no wonder. The final result, published in LIFE, evokes Dalí’s own work. The artist even painted an image directly onto the print before publication.

Before Halsman, portrait photography was often stilted and softly blurred, with a clear sense of detachment between the photographer and the subject. Halsman’s approach, to bring subjects such as Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe and Alfred Hitchcock into sharp focus as they moved before the camera, redefined portrait photography and inspired generations of photographers to collaborate with their subjects.

View From The Window At Le Gras, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, 1826

It took a unique combination of ingenuity and curiosity to produce the first known photograph, so it’s fitting that the man who made it was an inventor and not an artist. In the 1820s, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce had become fascinated with the printing method of lithography, in which images drawn on stone could be reproduced using oil-based ink. Searching for other ways to produce images, Niépce set up a device called a camera obscura, which captured and projected scenes illuminated by sunlight, and trained it on the view outside his studio window in eastern France. The scene was cast on a treated pewter plate that, after many hours, retained a crude copy of the buildings and rooftops outside. The result was the first known permanent photograph.

It is no overstatement to say that Niépce’s achievement laid the groundwork for the development of photography. Later, he worked with artist Louis Daguerre, whose sharper daguerreotype images marked photography’s next major advancement.

Leap Into Freedom, Peter Leibing, 1961

Following World War II, the conquering Allied governments carved Berlin into four occupation zones. Yet each part was not equal, and from 1949 to 1961 some 2.5 million East Germans fled the Soviet section in search of freedom. To stop the flow, East German leader Walter Ulbricht had a barbed-wire-and-cinder-block barrier thrown up in early August 1961. A few days later, Associated Press photographer Peter Leibing was tipped off that a defection might happen. He and other cameramen gathered and watched as a West Berlin crowd enticed 19-year-old border guard Hans Conrad Schumann, yelling to him, “Come on over!” Schumann, who later said he did not want to “live enclosed,” suddenly ran for the barricade. As he cleared the sharp wires he dropped his rifle and was whisked away. Sent out across the AP wire, Leibing’s photo ran on front pages across the world. It made Schumann, reportedly the first known East German soldier to flee, into a poster child for those yearning to be free, while lending urgency to East Germany’s push for a more permanent Berlin Wall. Schumann was sadly haunted by the weight of it all. While he quietly lived in the West, he could not grapple with his unintended stature as a symbol of freedom, and he committed suicide in 1998.

The Hand Of Mrs. Wilhelm Röntgen, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, 1895

There’s no way of knowing how many pictures were taken of Anna Bertha Röntgen, and most are surely lost to history. But one of them isn’t: it is of her hand—more precisely, the bones in her hand—an image captured by her husband Wilhelm when he took the first medical x-ray in 1895. Wilhelm had spent weeks working in his lab, experimenting with a cathode tube that emitted different frequencies of electromagnetic energy. Some, he noticed, appeared to penetrate solid objects and expose sheets of photographic paper. He used the strange rays, which he aptly dubbed x-rays, to create shadowy images of the inside of various inanimate objects and then, finally, one very animate one. The picture of Anna’s hand created a sensation, and the discovery of x-rays won Wilhelm the first Nobel Prize ever granted for physics in 1901. His breakthrough quickly went into use around the world, revolutionizing the diagnosis and treatment of injuries and illnesses that had always been hidden from sight. Anna, however, was never taken with the picture. “I have seen my death,” she said when she first glimpsed it. For many millions of other people, it has meant life.

What a brave woman! I don't know if I would be able to try as first person... she must really believed in her husband. This photo means me more than "just" the first photo about of the greatest inventions, it will always mean real trust and love to me. :)

Flag Raising On Iwo Jima, Joe Rosenthal, 1945

It is but a speck of an island 760 miles south of Tokyo, a volcanic pile that blocked the Allies’ march toward Japan. The Americans needed Iwo Jima as an air base, but the Japanese had dug in. U.S. troops landed on February 19, 1945, beginning a month of fighting that claimed the lives of 6,800 Americans and 21,000 Japanese. On the fifth day of battle, the Marines captured Mount Suribachi. An American flag was quickly raised, but a commander called for a bigger one, in part to inspire his men and demoralize his opponents. Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal lugged his bulky Speed Graphic camera to the top, and as five Marines and a Navy corpsman prepared to hoist the Stars and Stripes, Rosenthal stepped back to get a better frame—and almost missed the shot. “The sky was overcast,” he later wrote of what has become one of the most recognizable images of war. “The wind just whipped the flag out over the heads of the group, and at their feet the disrupted terrain and the broken stalks of the shrubbery exemplified the turbulence of war.” Two days later Rosenthal’s photo was splashed on front pages across the U.S., where it was quickly embraced as a symbol of unity in the long-fought war. The picture, which earned Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize, so resonated that it was made into a postage stamp and cast as a 100-ton bronze memorial.

I am a Mennonite, and thus a pacifist, like some of my ancestors going back for centuries, before the Revolutionary War, yet I also have ancestors who fought in that very war, and in the wars following, along with a father and other family who have served protecting our country. War is evil, and needs to be avoided at all times. But it isn't. And the men and women who have served and are serving need our help and support and respect. When you insult an image like this that is a symbol to them and the nation of that service, staged or not, you are being unfair and disrespectful and rude.

Emmett Till, David Jackson, 1955

In August 1955, Emmett Till, a black teenager from Chicago, was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he stopped at Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market. There he encountered Carolyn Bryant, a white woman. Whether Till really flirted with Bryant or whistled at her isn’t known. But what happened four days later is. Bryant’s husband Roy and his half brother, J.W. Milam, seized the 14-year-old from his great-uncle’s house. The pair then beat Till, shot him, and strung barbed wire and a 75-pound metal fan around his neck and dumped the lifeless body in the Tallahatchie River. A white jury quickly acquitted the men, with one juror saying it had taken so long only because they had to break to drink some pop. When Till’s mother Mamie came to identify her son, she told the funeral director, “Let the people see what I’ve seen.” She brought him home to Chicago and insisted on an open casket. Tens of thousands filed past Till’s remains, but it was the publication of the searing funeral image in Jet, with a stoic Mamie gazing at her murdered child’s ravaged body, that forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism. For almost a century, African Americans were lynched with regularity and impunity. Now, thanks to a mother’s determination to expose the barbarousness of the crime, the public could no longer pretend to ignore what they couldn’t see.

While lynching are now illegal, we see other forms of systematic racism and discrimination plaguing the United States. We have an overwhelming number of minorities gracing our prisons and getting paid less than .25 cents to create what we use in our everyday lives. We see the prison industrial complex sentence an alarming number of minorities to tough sentences for a small baggie of marijuana and other petty crimes. While men like Brock Turner get a few months in jail for rape. Our system is flawed and Americans with a conscience are tired of the injustice.

Cotton Mill Girl, Lewis Hine, 1908

Working as an investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, Lewis Hine believed that images of child labor would force citizens to demand change. The muckraker conned his way into mills and factories from Massachusetts to South Carolina by posing as a Bible seller, insurance agent or industrial photographer in order to tell the plight of nearly 2 million children. Carting around a large-format camera and jotting down information in a hidden notebook, Hine recorded children laboring in meatpacking houses, coal mines and canneries, and in November 1908 he came upon Sadie Pfeifer, who embodied the world he exposed. A 48-inch-tall wisp of a girl, she was “one of the many small children at work” manning a gargantuan cotton-spinning machine in Lancaster, S.C. Since Hine often had to lie to get his shots, he made “double-sure that my photo data was 100% pure—no retouching or fakery of any kind.” His images of children as young as 8 dwarfed by the cogs of a cold, mechanized universe squarely set the horrors of child labor before the public, leading to regulatory legislation and cutting the number of child laborers nearly in half from 1910 to 1920.

and nearly a hundred years on we have moved this image to asia and south america.

Hitler At A Nazi Party Rally, Heinrich Hoffmann, 1934

Spectacle was like oxygen for the Nazis, and Heinrich Hoffmann was instrumental in staging Hitler’s growing pageant of power. Hoffmann, who joined the party in 1920 and became Hitler’s personal photographer and confidant, was charged with choreographing the regime’s propaganda carnivals and selling them to a wounded German public. Nowhere did Hoffmann do it better than on September 30, 1934, in his rigidly symmetrical photo at the Bückeberg Harvest Festival, where the Mephistophelian Führer swaggers at the center of a grand Wagnerian fantasy of adoring and heiling troops. By capturing this and so many other extravaganzas, Hoffmann—who took more than 2 million photos of his boss—fed the regime’s vast propaganda machine and spread its demonic dream. Such images were all-pervasive in Hitler’s Reich, which shrewdly used Hoffman’s photos, the stark graphics on Nazi banners and the films of Leni Riefenstahl to make Aryanism seem worthy of godlike worship. Humiliated by World War I, punishing reparations and the Great Depression, a nation eager to reclaim its sense of self was rallied by Hitler’s visage and his seemingly invincible men aching to right wrongs. Hoffmann’s expertly rendered propaganda is a testament to photography’s power to move nations and plunge a world into war.

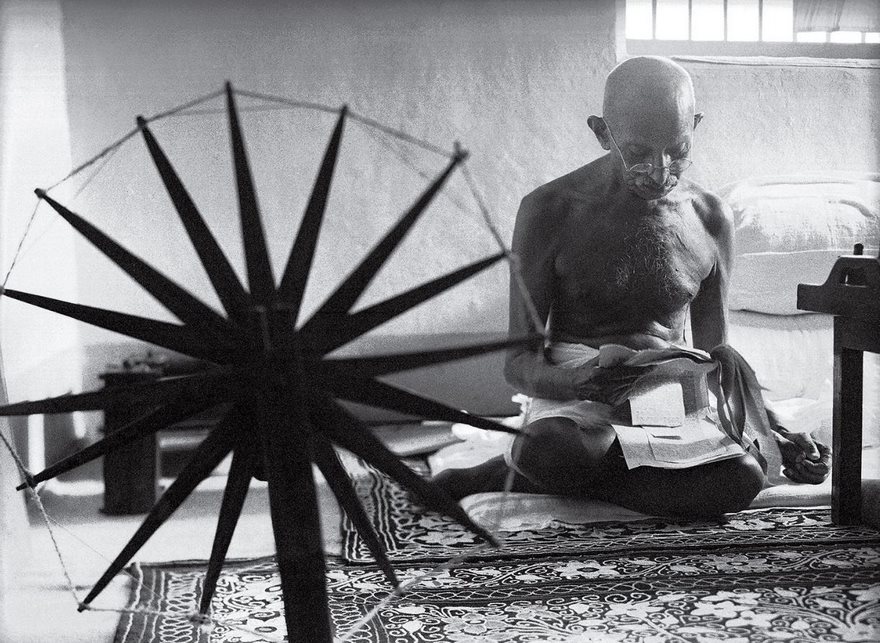

Gandhi And The Spinning Wheel, Margaret Bourke-White, 1946

When the British held Mohandas Gandhi prisoner at Yeravda prison in Pune, India, from 1932 to 1933, the nationalist leader made his own thread with a charkha, a portable spinning wheel. The practice evolved from a source of personal comfort during captivity into a touchstone of the campaign for independence, with Gandhi encouraging his countrymen to make their own homespun cloth instead of buying British goods. By the time Margaret Bourke-White came to Gandhi’s compound for a life article on India’s leaders, spinning was so bound up with Gandhi’s identity that his secretary, Pyarelal Nayyar, told Bourke-White that she had to learn the craft before photographing the leader. Bourke-White’s picture of Gandhi reading the news alongside his charkha never appeared in the article for which it was taken, but less than two years later life featured the photo prominently in a tribute published after Gandhi’s assassination. It soon became an indelible image, the slain civil-disobedience crusader with his most potent symbol, and helped solidify the perception of Gandhi outside the subcontinent as a saintly man of peace.

Fetus, 18 Weeks, Lennart Nilsson, 1965

When LIFE published Lennart Nilsson’s photo essay “Drama of Life Before Birth” in 1965, the issue was so popular that it sold out within days. And for good reason. Nilsson’s images publicly revealed for the first time what a developing fetus looks like, and in the process raised pointed new questions about when life begins. In the accompanying story, LIFE explained that all but one of the fetuses pictured were photographed outside the womb and had been removed—or aborted—“for a variety of medical reasons.” Nilsson had struck a deal with a hospital in Stockholm, whose doctors called him whenever a fetus was available to photograph. There, in a dedicated room with lights and lenses specially designed for the project, Nilsson arranged the fetuses so they appeared to be floating as if in the womb.

In the years since Nilsson’s essay was published, the images have been widely appropriated without his permission. Antiabortion activists in particular have used them to advance their cause. (Nilsson has never taken a public stand on abortion.) Still, decades after they first appeared, Nilsson’s images endure for their unprecedentedly clear, detailed view of human life at its earliest stages.

D-Day, Robert Capa, 1944

It was the invasion to save civilization, and LIFE’s Robert Capa was there, the only still photographer to wade with the 34,250 troops onto Omaha Beach during the D-Day landing. His photographs—infused with jarring movement from the center of that brutal assault—gave the public an American soldier’s view of the dangers of war. The soldier in this case was Private First Class Huston Riley, who after the Nazis shelled his landing craft jumped into water so deep that he had to walk along the bottom until he could hold his breath no more. When he activated his Navy M-26 belt life preservers and floated to the surface, Riley became a target for the guns and artillery shells mowing down his comrades. Struck several times, the 22-year-old soldier took about half an hour to reach the Normandy shore. Capa took this photo of him in the surf and then with the assistance of a sergeant helped Riley, who later recalled thinking, “What the hell is this guy doing here? I can’t believe it. Here’s a cameraman on the shore.” Capa spent an hour and a half under fire as men around him died. A courier then transported his four rolls of film to LIFE’s London offices, and the magazine’s general manager stopped the presses to get them into the June 19 issue. Most of the film, though, showed no images after processing, and only some frames survived. The remaining images have a grainy, blurry look that gives them the frenetic feel of action, a quality that has come to define our collective memory of that epic clash.

The Pillow Fight, Harry Benson, 1964

Harry Benson didn’t want to meet the Beatles. The Glasgow-born photographer had plans to cover a news story in Africa when he was assigned to photograph the musicians in Paris. “I took myself for a serious journalist and I didn’t want to cover a rock ’n’ roll story,” he scoffed. But once he met the boys from Liverpool and heard them play, Benson had no desire to leave. “I thought, ‘God, I’m on the right story.’ ” The Beatles were on the cusp of greatness, and Benson was in the middle of it. His pillow-fight photo, taken in the swanky George V Hotel the night the band found out “I Want to Hold Your Hand” hit No. 1 in the U.S., freezes John, Paul, George and Ringo in an exuberant cascade of boyish talent—and perhaps their last moment of unbridled innocence. It captures the sheer joy, happiness and optimism that would be embraced as Beatlemania and that helped lift America’s morale just 11 weeks after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The following month, Benson accompanied the Fab Four as they flew to New York City to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, kick-starting the British Invasion. The trip led to decades of collaboration with the group and, as Benson later recalled, “I was so close to not being there.”

The Face Of Aids, Therese Frare, 1990

David Kirby died surrounded by his family. But Therese Frare’s photograph of the 32-year-old man on his deathbed did more than just capture the heartbreaking moment. It humanized AIDS, the disease that killed Kirby, at a time when it was ravaging victims largely out of public view. Frare’s photograph, published in LIFE in 1990, showed how the widely misunderstood disease devastated more than just its victims. It would be another year before the red ribbon became a symbol of compassion and resilience, and three years before President Bill Clinton created a White House Office of National AIDS Policy. In 1992 the clothing company Benetton used a colorized version of Frare’s photograph in a series of provocative ads. Many magazines refused to run it, and a range of groups called for a boycott. But Kirby’s family consented to its use, believing that the ad helped raise critical awareness about AIDS at a moment when the disease was still uncontrolled and sufferers were lobbying the federal government to speed the development of new drugs. “We just felt it was time that people saw the truth about AIDS,” Kirby’s mother Kay said. Thanks to Frare’s image, they did.

First Cell-Phone Picture, Philippe Kahn, 1997

Boredom can be a powerful incentive. In 1997, Philippe Kahn was stuck in a Northern California maternity ward with nothing to do. The software entrepreneur had been shooed away by his wife while she birthed their daughter, Sophie. So Kahn, who had been tinkering with technologies that share images instantly, jerry-built a device that could send a photo of his newborn to friends and family—in real time. Like any invention, the setup was crude: a digital camera connected to his flip-top cell phone, synched by a few lines of code he’d written on his laptop in the hospital. But the effect has transformed the world: Kahn’s device captured his daughter’s first moments and transmitted them instantly to more than 2,000 people.

Kahn soon refined his ad hoc prototype, and in 2000 Sharp used his technology to release the first commercially available integrated camera phone, in Japan. The phones were introduced to the U.S. market a few years later and soon became ubiquitous. Kahn’s invention forever altered how we communicate, perceive and experience the world and laid the groundwork for smartphones and photo-sharing applications like Instagram and Snapchat. Phones are now used to send hundreds of millions of images around the world every day—including a fair number of baby pictures.

The invention was of course influential but not sure if this image was....

Raising A Flag Over The Reichstag, Yevgeny Khaldei, 1945

“This is what I was waiting for for 1,400 days,” the Ukrainian-born Yevgeny Khaldei said as he gazed at the ruins of Berlin on May 2, 1945. After four years of fighting and photographing across Eastern Europe, the Red Army soldier arrived in the heart of the Nazis’ homeland armed with his Leica III rangefinder and a massive Soviet flag that his uncle, a tailor, had fashioned for him from three red tablecloths. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide two days before, yet the war still raged as Khaldei made his way to the Reichstag. There he told three soldiers to join him, and they clambered up broken stairs onto the parliament building’s blood-soaked parapet. Gazing through his camera, Khaldei knew he had the shot he had hoped for: “I was euphoric.” In printing, Khaldei dramatized the image by intensifying the smoke and darkening the sky—even scratching out part of the negative—to craft a romanticized scene that was part reality, part artifice and all patriotism. Published in the Russian magazine Ogonek, the image became an instant propaganda icon. And no wonder. The flag jutting from the heart of the enemy exalted the nobility of communism, proclaimed the Soviets the new overlords and hinted that by lowering the curtain of war, Premier Joseph Stalin would soon hoist a cold new iron one across the land.

I want to make a note here. The picture presented above is actually an edited version of the original take. During the developing process, and before the official publication, a second watch was removed from soldier's forearm to prevent from shaming of USSR (crf picture attached). The-Soviet...3f2067.jpg

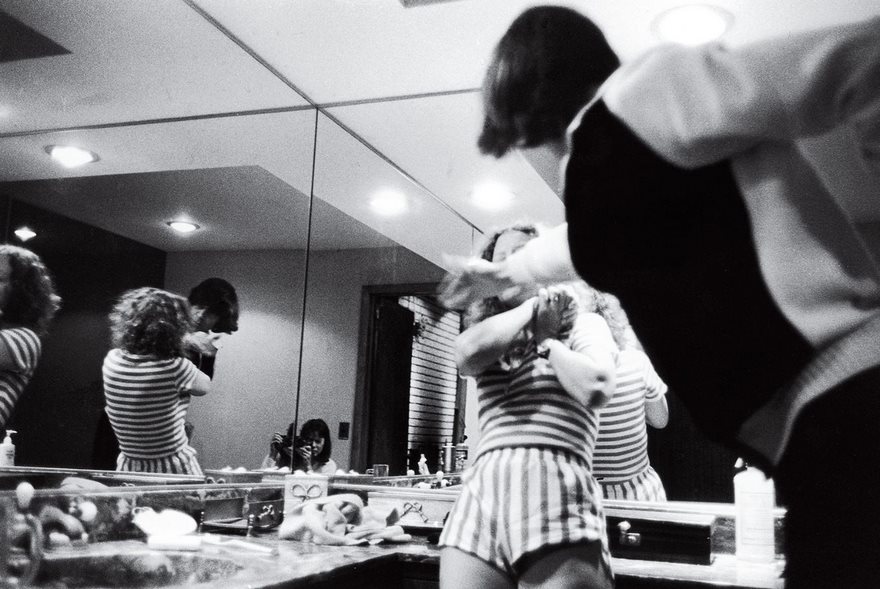

Behind Closed Doors, Donna Ferrato, 1982

There was nothing particularly special about Garth and Lisa or the violence that happened in the bathroom of their suburban New Jersey home one night in 1982. Enraged by a perceived slight, Garth beat his wife while she cowered in a corner. Such acts of intimate-partner violence are not uncommon, but they usually happen in private. This time another person was in the room, photographer Donna Ferrato.

Ferrato, who had come to know the couple through a photo project on wealthy swingers, knew that simply bearing witness wasn’t enough. Her shutter clicked again and again. Ferrato approached magazine editors to publish the images, but all refused. So Ferrato did, in her 1991 book Living With the Enemy. The landmark volume chronicled domestic-violence episodes and their aftermaths, including those of the pseudonymous Garth and Lisa. Their real names are Elisabeth and Bengt; his identity was revealed for the first time as part of this project. Ferrato captured incidents and victims while living inside women’s shelters and shadowing police. Her work helped bring violence against women out of the shadows and forced policymakers to confront the issue. In 1994, Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act, increasing penalties against offenders and helping train police to treat it as a serious crime. Thanks to Ferrato, a private tragedy became a public cause.

It's sad that it took America until 1994 to pass laws that would protect women. Always oddly behind when it comes to things that matter. Maybe by 2020 we can take a hard look at our education system and bring our schools to the same level that Europe enjoys now.

Famine In Somalia, James Nachtwey, 1992

James Nachtwey couldn’t get an assignment in 1992 to document the spiraling famine in Somalia. Mogadishu had become engulfed in armed conflict as food prices soared and international assistance failed to keep pace. Yet few in the West took much notice, so the American photographer went on his own to Somalia, where he received support from the International Committee of the Red Cross. Nachtwey brought back a cache of haunting images, including this scene of a woman waiting to be taken to a feeding center in a wheelbarrow. After it was published as part of a cover feature in the New York Times Magazine, one reader wrote, “Dare we say that it doesn’t get any worse than this?” The world was similarly moved. The Red Cross said public support resulted in what was then its largest operation since World War II. One and a half million people were saved, the ICRC’s Jean-Daniel Tauxe told the Times, and “James’ pictures made the difference.”

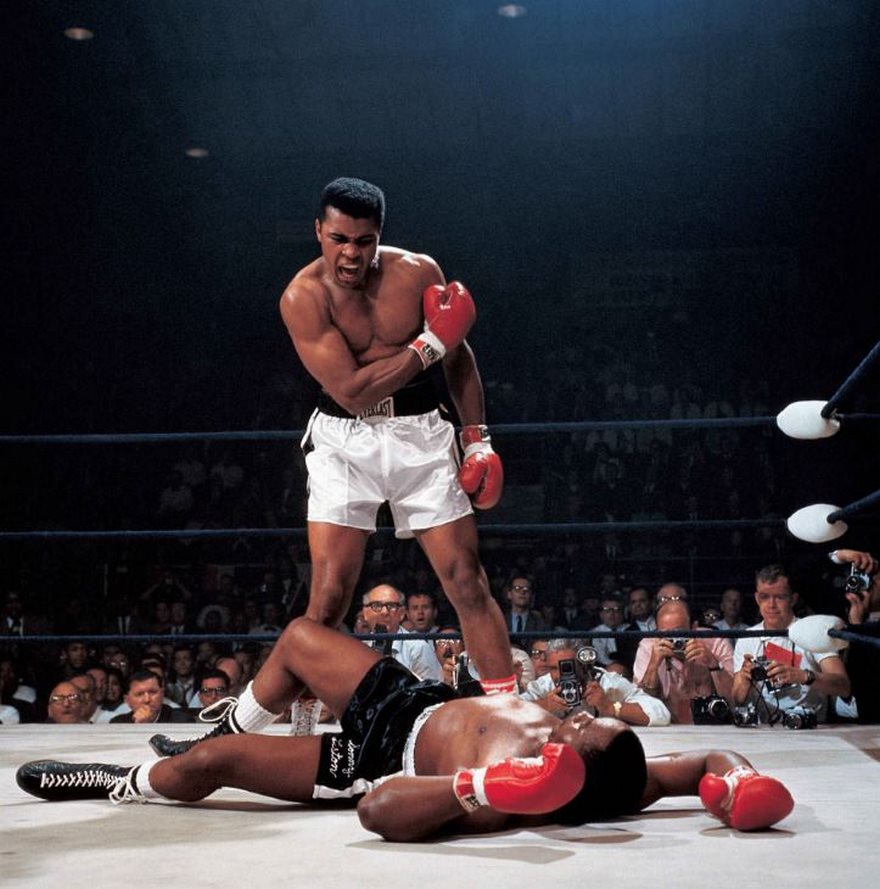

Muhammad Ali Vs. Sonny Liston, Neil Leifer, 1965

So much of great photography is being in the right spot at the right moment. That was what it was like for sports illustrated photographer Neil Leifer when he shot perhaps the greatest sports photo of the century. “I was obviously in the right seat, but what matters is I didn’t miss,” he later said. Leifer had taken that ringside spot in Lewiston, Maine, on May 25, 1965, as 23-year-old heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali squared off against 34-year-old Sonny Liston, the man he’d snatched the title from the previous year. One minute and 44 seconds into the first round, Ali’s right fist connected with Liston’s chin and Liston went down. Leifer snapped the photo of the champ towering over his vanquished opponent and taunting him, “Get up and fight, sucker!” Powerful overhead lights and thick clouds of cigar smoke had turned the ring into the perfect studio, and Leifer took full advantage. His perfectly composed image captures Ali radiating the strength and poetic brashness that made him the nation’s most beloved and reviled athlete, at a moment when sports, politics and popular culture were being squarely battered in the tumult of the ’60s.

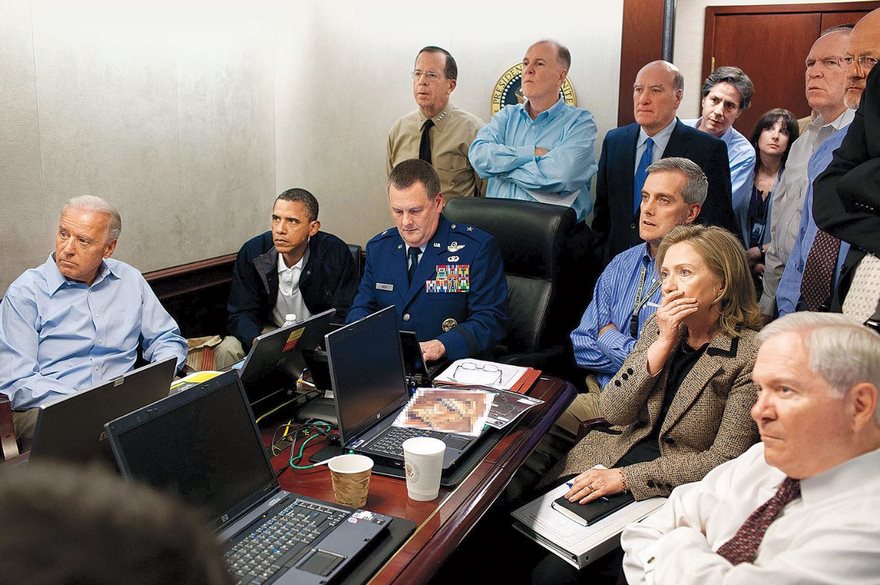

The Situation Room, Pete Souza, 2011

Official White House photographers document Presidents at play and at work, on the phone with world leaders and presiding over Oval Office meetings. But sometimes the unique access allows them to capture watershed moments that become our collective memory. On May 1, 2011, Pete Souza was inside the Situation Room as U.S. forces raided Osama bin Laden’s Pakistan compound and killed the terrorist leader. Yet Souza’s picture includes neither the raid nor bin Laden. Instead he captured those watching the secret operation in real time. President Barack Obama made the decision to launch the attack, but like everyone else in the room, he is a mere spectator to its execution. He stares, brow furrowed, at the raid unfolding on monitors. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton covers her mouth, waiting to see its outcome.

In a national address that evening from the White House, Obama announced that bin Laden had been killed. Photographs of the dead body have never been released, leaving Souza’s photo and the tension it captured as the only public image of the moment the war on terror notched its most important victory.

The Bin Laden family's construction business is still in business. Perhaps the fact they are currently building the tallest skyscraper on Earth (In Jeddah, Saudi Arabia) will strike some of you as ironic - some of the family have relocated. To the USA. DISCLAIMER - Neither the company nor the people involved are implicated in the hideous atrocities committed by Osama bin Laden.

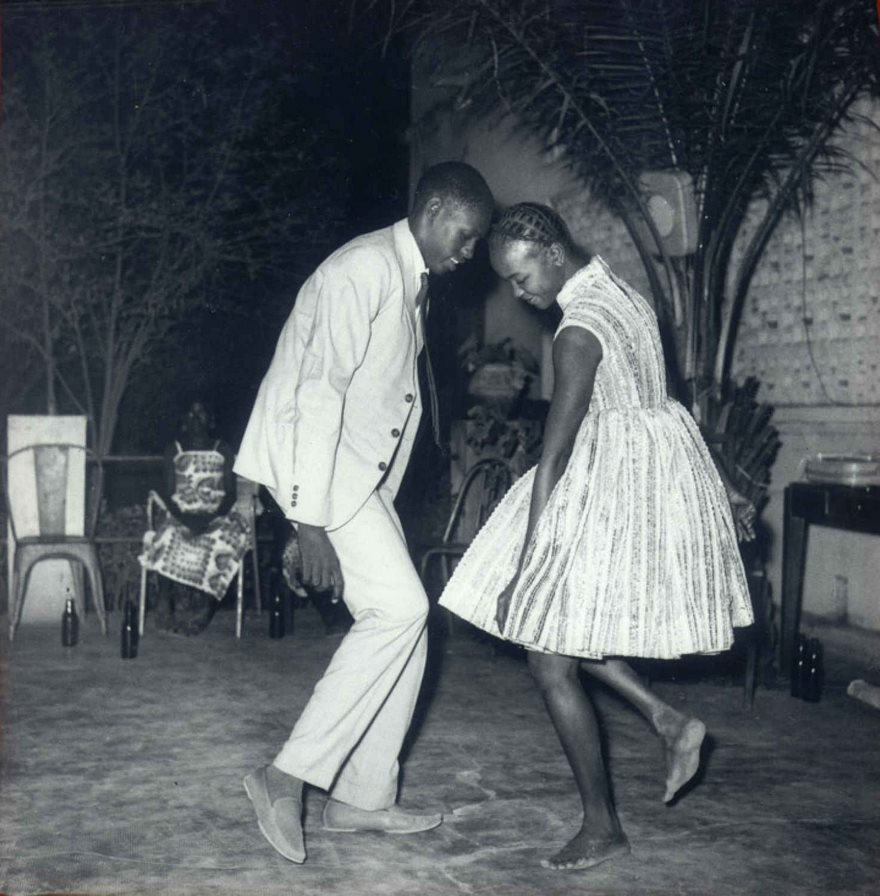

Nuit De Noel, Malick Sidibe, 1963

Malian photographer Malick Sidibé’s life followed the trajectory of his nation. He started out herding his family’s goats, then trained in jewelry making, painting and photography. As French colonial rule ended in 1960, he captured the subtle and profound changes reshaping his nation. Nicknamed the Eye of Bamako, Sidibé took thousands of photos that became a real-time chronicle of the euphoric zeitgeist gripping the capital, a document of a fleeting moment. “Everyone had to have the latest Paris style,” he observed of young people wearing flashy clothes, straddling Vespas and nuzzling in public as they embraced a world without shackles. On Christmas Eve in 1963, Sidibé happened on a young couple at a club, lost in each other’s eyes. What Sidibé called his “talent to observe” allowed him to capture their quiet intimacy, heads brushing as they grace an empty dance floor. “We were entering a new era, and people wanted to dance,” Sidibé said. “Music freed us. Suddenly, young men could get close to young women, hold them in their hands. Before, it was not allowed. And everyone wanted to be photographed dancing up close.”

Saigon Execution, Eddie Adams, 1968

The act was stunning in its casualness. Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams was on the streets of Saigon on February 1, 1968, two days after the forces of the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong set off the Tet offensive and swarmed into dozens of South Vietnamese cities. As Adams photographed the turmoil, he came upon Brigadier General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, chief of the national police, standing alongside Nguyen Van Lem, the captain of a terrorist squad who had just killed the family of one of Loan’s friends. Adams thought he was watching the interrogation of a bound prisoner. But as he looked through his viewfinder, Loan calmly raised his .38-caliber pistol and summarily fired a bullet through Lem’s head. After shooting the suspect, the general justified the suddenness of his actions by saying, “If you hesitate, if you didn’t do your duty, the men won’t follow you.” The Tet offensive raged into March. Yet while U.S. forces beat back the communists, press reports of the anarchy convinced Americans that the war was unwinnable. The freezing of the moment of Lem’s death symbolized for many the brutality over there, and the picture’s widespread publication helped galvanize growing sentiment in America about the futility of the fight. More important, Adams’ photo ushered in a more intimate level of war photojournalism. He won a Pulitzer Prize for this image, and as he commented three decades later about the reach of his work, “Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world.”

Black Power Salute, John Dominis, 1968

The Olympics are intended to be a celebration of global unity. But when the American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos ascended the medal stand at the 1968 Games in Mexico City, they were determined to shatter the illusion that all was right in the world. Just before “The Star-Spangled Banner” began to play, Smith, the gold medalist, and Carlos, the bronze winner, bowed their heads and raised black-gloved fists in the air. Their message could not have been clearer: Before we salute America, America must treat blacks as equal. “We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat,” Carlos later said. John Dominis, a quick-fingered life photographer known for capturing unexpected moments, shot a close-up that revealed another layer: Smith in black socks, his running shoes off, in a gesture meant to symbolize black poverty. Published in life, Dominis’ image turned the somber protest into an iconic emblem of the turbulent 1960s.

The man silently standing to the left is Australian. He never participated in the Olympics again due to his support for the black Americans. When he died, both the Amwricans attended his funeral back in Australia. A movie was made about this Aussie too.

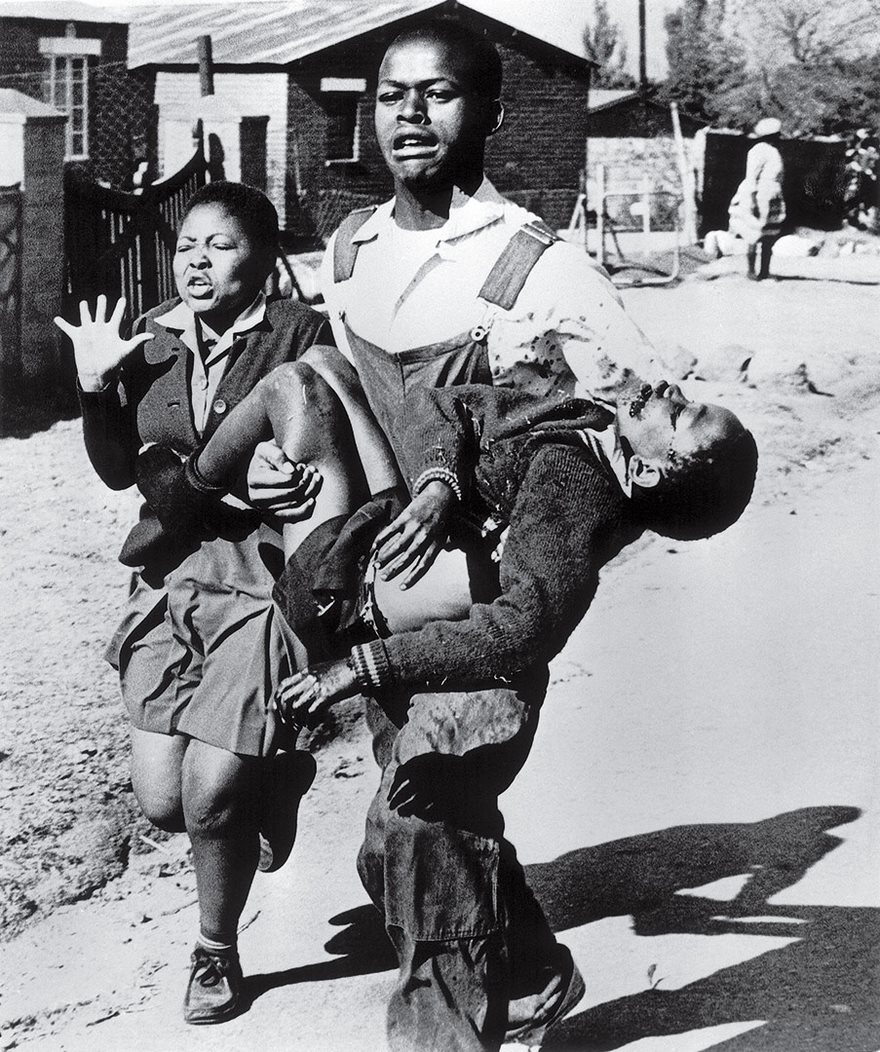

Soweto Uprising, Sam Nzima, 1976

Few outside South Africa paid much attention to apartheid before June 16, 1976, when several thousand Soweto students set out to protest the introduction of mandatory Afrikaans-language instruction in their township schools. Along the way they gathered youngsters from other schools, including a 13-year-old student named Hector Pieterson. Skirmishes started to break out with the police, and at one point officers fired tear gas. When students hurled stones, the police shot real bullets into the crowd. “At first, I ran away from the scene,” recalled Sam Nzima, who was covering the protests for the World, the paper that was the house organ of black Johannesburg. “But then, after recovering myself, I went back.” That is when Nzima says he spotted Pieterson fall down as gunfire showered above. He kept taking pictures as terrified high schooler Mbuyisa Makhubu picked up the lifeless boy and ran with Pieterson’s sister, Antoinette Sithole. What began as a peaceful protest soon turned into a violent uprising, claiming hundreds of lives across South Africa. Prime Minister John Vorster warned, “This government will not be intimidated.” But the armed rulers were powerless against Nzima’s photo of Pieterson, which showed how the South African regime killed its own people. The picture’s publication forced Nzima into hiding amid death threats, but its effect could not have been more visible. Suddenly the world could no longer ignore apartheid. The seeds of international opposition that would eventually topple the racist system had been planted by a photograph.

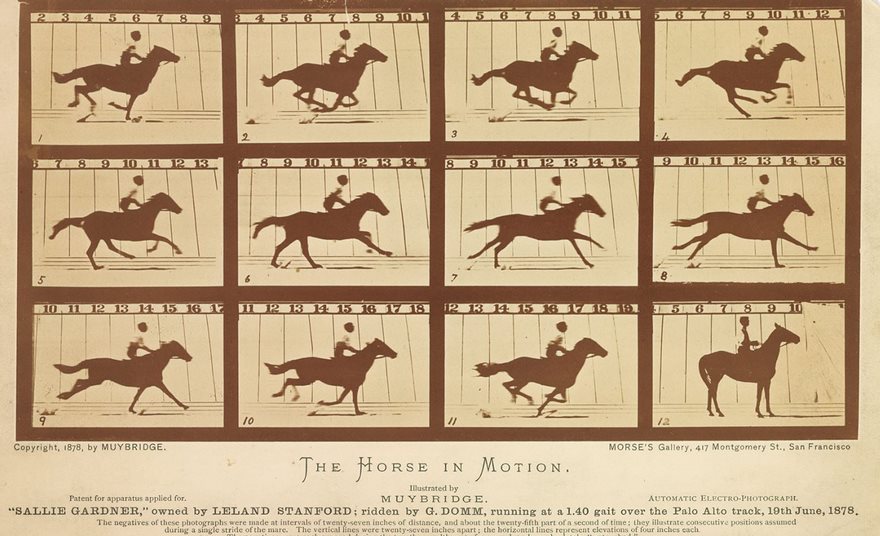

The Horse In Motion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1878

When a horse trots or gallops, does it ever become fully airborne? This was the question photographer Eadweard Muybridge set out to answer in 1878. Railroad tycoon and former California governor Leland Stanford was convinced the answer was yes and commissioned Muybridge to provide proof. Muybridge developed a way to take photos with an exposure lasting a fraction of a second and, with reporters as witnesses, arranged 12 cameras along a track on Stanford’s estate.

As a horse sped by, it tripped wires connected to the cameras, which took 12 photos in rapid succession. Muybridge developed the images on site and, in the frames, revealed that a horse is completely aloft with its hooves tucked underneath it for a brief moment during a stride. The revelation, imperceptible to the naked eye but apparent through photography, marked a new purpose for the medium. It could capture truth through technology. Muybridge’s stop-motion technique was an early form of animation that helped pave the way for the motion-picture industry, born a short decade later.

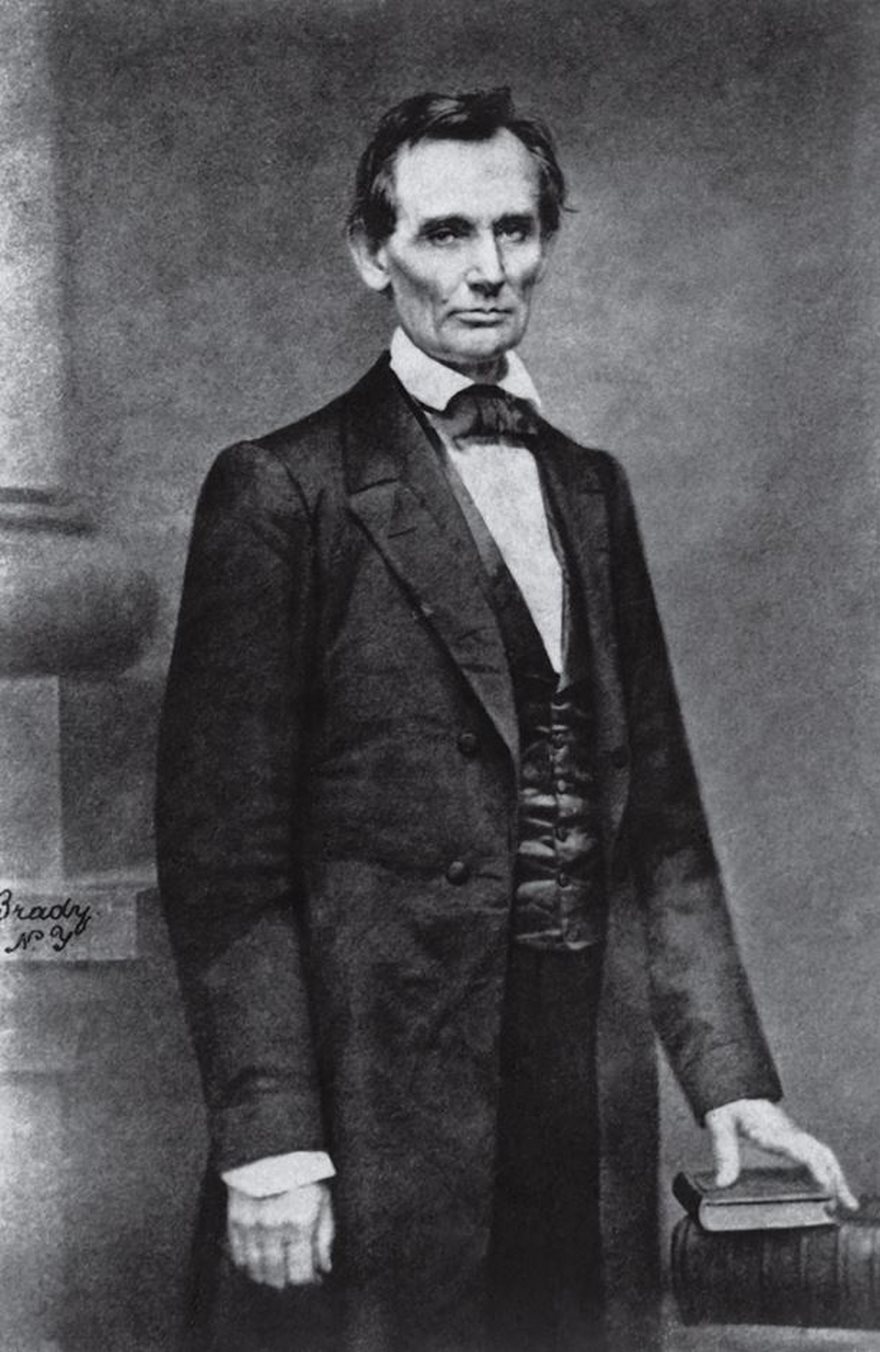

Abraham Lincoln, Mathew Brady, 1860

Abraham Lincoln was a little-known one-term Illinois Congressman with national aspirations when he arrived in New York City in February 1860 to speak at the Cooper Union. The speech had to be perfect, but Lincoln also knew the importance of image. Before taking to the podium, he stopped at the Broadway photography studio of Mathew B. Brady. The portraitist, who had photographed everyone from Edgar Allan Poe to James Fenimore Cooper and would chronicle the coming Civil War, knew a thing or two about presentation. He set the gangly rail splitter in a statesmanlike pose, tightened his shirt collar to hide his long neck and retouched the image to improve his looks. In a click of a shutter, Brady dispelled talk of what Lincoln said were “rumors of my long ungainly figure … making me into a man of human aspect and dignified bearing.” By capturing Lincoln’s youthful features before the ravages of the Civil War would etch his face with the strains of the Oval Office, Brady presented him as a calm contender in the fractious antebellum era. Lincoln’s subsequent talk before a largely Republican audience of 1,500 was a resounding success, and Brady’s picture soon appeared in publications like Harper’s Weekly and on cartes de visite and election posters and buttons, making it the most powerful early instance of a photo used as campaign propaganda. As the portrait spread, it propelled Lincoln from the edge of greatness to the White House, where he preserved the Union and ended slavery. As Lincoln later admitted, “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me President of the United States.”

Iraqi Girl At Checkpoint, Chris Hondros, 2005

Moments before American photojournalist Chris Hondros took this picture of Samar Hassan, the little girl was in the backseat of her family’s car as they drove home from the Iraqi city of Tall ‘Afar. Now Samar was an orphan, her parents shot dead by U.S. soldiers who had opened fire because they feared the car might be carrying insurgents or a suicide bomber. It was January 2005, and the war in Iraq was at its most brutal. Such horrific accidents were not rare in that chaotic conflict, but they had never been documented in real time. Hondros, who worked for Getty Images, was embedded with the Army unit when the shooting happened. He transmitted his photographs immediately, and by the following day they were published around the world. The images led the U.S. military to revise its checkpoint procedures, but their greater effect was in compelling an already skeptical public to ask why American soldiers were killing the people they had ostensibly come to liberate and protect.

Hondros was killed during the civil war in Libya in 2011.

Gorilla In The Congo, Brent Stirton, 2007

Senkwekwe the silverback mountain gorilla weighed at least 500 pounds when his carcass was strapped to a makeshift stretcher, and it took more than a dozen men to hoist it into the air. Brent Stirton captured the scene while in Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Senkwekwe and several other gorillas were shot dead as a violent conflict engulfed the park, where half the world’s critically endangered mountain gorillas live.

When Stirton photographed residents and park rangers respectfully carrying Senkwekwe out of the forest in 2007, the park was under siege by people illegally harvesting wood to be used in a charcoal industry that grew in the wake of the Rwandan genocide. In the photo, Senkwekwe looks huge but vaguely human, a reminder that conflict in Central Africa affects more than just the humans caught in its cross fire; it also touches the region’s environment and animal inhabitants. Three months after Stirton’s photograph was published in Newsweek, nine African countries—including Congo—signed a legally binding treaty to help protect the mountain gorillas in Virunga.

I'm shocked at how people could treat animals like this, we've become so entitled, even if it's for survival reasons this shouldn't be done.

Bandit's Roost, Mulberry Street, Jacob Riis, Circa 1888

Late 19th-century New York City was a magnet for the world’s immigrants, and the vast majority of them found not streets paved with gold but nearly subhuman squalor. While polite society turned a blind eye, brave reporters like the Danish-born Jacob Riis documented this shame of the Gilded Age. Riis did this by venturing into the city’s most ominous neighborhoods with his blinding magnesium flash powder lights, capturing the casual crime, grinding poverty and frightful overcrowding. Most famous of these was Riis’ image of a Lower East Side street gang, which conveys the danger that lurked around every bend. Such work became the basis of his revelatory book How the Other Half Lives, which forced Americans to confront what they had long ignored and galvanized reformers like the young New York politician Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote to the photographer, “I have read your book, and I have come to help.” Riis’ work was instrumental in bringing about New York State’s landmark Tenement House Act of 1901, which improved conditions for the poor. And his crusading approach and direct, confrontational style ushered in the age of documentary and muckraking photojournalism.

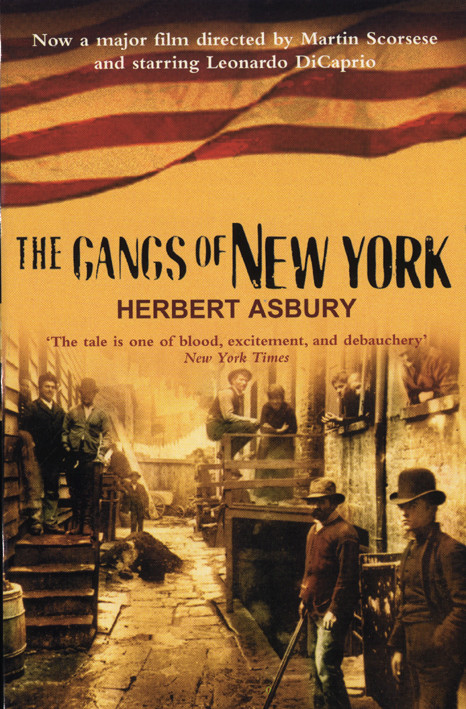

This picture was used as the cover of Herbert Asbury's Gangs of New York, from which Scorsese's came. I got a copy of the book at the time the movie was out and I was convinced that this was a set still from the movie mainly because I thought this was Leonardo DiCaprio on the right. Now I'm amazed to find out that its not. eWEIl7s-58...8130d5.jpg

Milk Drop Coronet, Harold Edgerton, 1957

Before Harold Edgerton rigged a milk dropper next to a timer and a camera of his own invention, it was virtually impossible to take a good photo in the dark without bulky equipment. It was similarly futile to try to photograph a fleeting moment. But in the 1950s at his lab at MIT, Edgerton started tinkering with a process that would change the future of photography. There the electrical-engineering professor combined high-tech strobe lights with camera shutter motors to capture moments imperceptible to the naked eye. Milk Drop Coronet, his revolutionary stop-motion photograph, freezes the impact of a drop of milk on a table, a crown of liquid discernible to the camera for only a millisecond. The picture proved that photography could advance human understanding of the physical world, and the technology Edgerton used to take it laid the foundation for the modern electronic flash.

Edgerton worked for years to perfect his milk-drop photographs, many of which were black and white; one version was featured in the first photography exhibition at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, in 1937. And while the man known as Doc captured other blink-and-you-missed-it moments, like balloons bursting and a bullet piercing an apple, his milk drop remains a quintessential example of photography’s ability to make art out of evidence.

Surfing Hippos, Michael Nichols, 2000

Seven billion human beings take up a certain amount of space, which is one reason why wilderness—true, untouched wilderness—is fast dwindling around the world. Even in Africa, where lions and elephants still roam, the space for wild animals is shrinking. That’s what makes Michael Nichols’ photograph so special. Nichols and the National Geographic Society explorer Michael Fay undertook an arduous 2,000-mile trek from the Congo in central Africa to Gabon on the continent’s west coast. That was where Nichols captured a photograph of something astonishing—hippopotamuses swimming in the midnight blue Atlantic Ocean. It was an event few had seen before—while hippos spend most of their time in water, their habitat is more likely to be an inland river or swamp than the crashing sea.

The photograph itself is reliably beautiful, the eyes and snout of the hippo peeking just above the rippling ocean surface. But its effect was more than aesthetic. Gabon President Omar Bongo was inspired by Nichols’ pictures to create a system of national parks that now cover 11 percent of the country, ensuring that there will be at least some space left for the wild.

Moonlight: The Pond, Edward Steichen, 1904

Is Edward Steichen’s ethereal image a photograph or a painting? It’s both, and that was exactly his point. Steichen photographed the wooded scene in Mamaroneck, N.Y., hand-colored the black-and-white prints with blue tones and may have even added the glowing moon. The blurring of two mediums was the aim of Pictorialism, which was embraced by professional photographers at the turn of the 20th century as a way to differentiate their work from amateur snapshots taken with newly available handheld cameras. And no single image was more formative than Moonlight.

The year before he created Moonlight, Steichen wrote an essay arguing that altering photos was no different than choosing when and where to click the shutter. Photographers, he said, always have a perspective that necessarily distorts the authenticity of their images. Although Steichen eventually abandoned Pictorialism, the movement’s influence can be seen in every photographer who seeks to create scenes, not merely capture them. Moonlight, too, continues to resonate. A century after Steichen made the image, a print sold for nearly $3 million.

The Vanishing Race, Edward S. Curtis, 1904