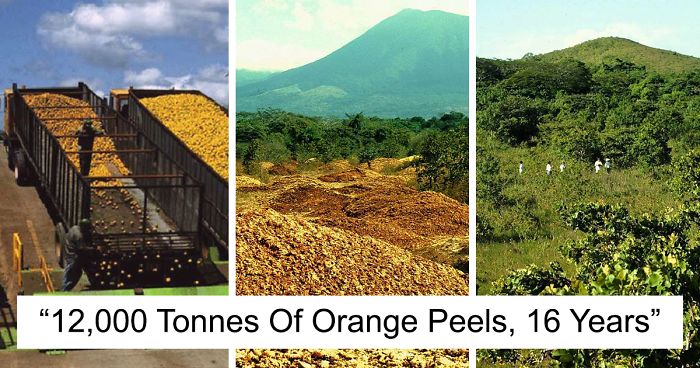

Juice Company Dumped 12,000 Tonnes Of Orange Peels On Virtually Lifeless Soil, 16 Years Later, It Turned Into A Lush Forest

The environmental impact of mismanaged trash and landfill sites has proved to have devastating consequences. The development of a landfill site typically means the loss of approximately 30 to 300 species per hectare – but in the case of one Costa Rican dump site – one man’s trash became the forest’s treasure.

What began as a land dumpsite agreement between a fruit juice company and a national park blossomed into a fruitful land conservation experiment, that revitalized the area 15-years after the dumping stopped. With the burgeoning of eco-projects all around the world to try and restore the land, we’ve destroyed environmentalists could learn something from orange peel dump.

In 1997 Costa Rica agreed to let a juice company dump their orange peels into the forest – 16-years later researchers peeled back the layers to reveal an ecological conservation success story

Image credits: Princeton University

It all began in 1997 when two ecologists from the University of Pennsylvania partnered with a young fruit juice company called Del Oro, that was based in Costa Rica. The company owned land that bordered with the Guanacaste Conservation Area, a national park located in the northwestern corner of the country, which the conservation organization wanted to acquire – so a deal was struck

Image credits: Princeton University

In exchange for the borderland that Del Oro owned, they would sign it over under the pretext that they would be allowed to dump some of their agricultural waste in designated park areas. The idea of allowing dump sites on conservation land may seem crazy, but it was well thought out.

Image credits: Princeton University

Del Oro does not use pesticides or insecticides and they were only allowed to dispose of certain agricultural waste – mainly orange peels and orange pulp. In addition, the designated trash sites were all on parts of the park that were degraded – which means they had poor soil quality. With the agreement, the park expanded its boundaries and the company had a monitored waste system.

Image credits: Princeton University

Not everyone was happy with the arrangement, however, a rival fruit company called TicoFrut—”tico” came after Del Oro and sued them. Their claim was that the dumping was dangerous, causing piles of rotting peels and flies and more importantly for them – unfair. Their envy was based in a prior incident where TicoFrut had been forced to overhaul their company’s own waste-processing facility. An all-out media war was waged against Del Oro’s dumping experiment and the country turned against them. Despite support and evidence from environmental groups like Rainforest Alliance, assuring the project was ecologically safe, the Costa Rican Supreme Court shut them down.

Image credits: Princeton University

The uproar did not come as a shock. Costa Rica has led the world in environmental protection since the 1980s, which has benefited the stunning biodiversity of the country and stimulated their economy. The small country only makes up 0.03 percent of the world’s landmass but 6 percent of this is biodiversity. Through government regulations, twenty-five percent of the country is under federal protection. Costa Ricans are proud of their ecologically-conscious culture, which also creates tens of thousands of jobs through the ecotourism and environmental protection sectors.

Image credits: Princeton University

Over the course of the project, 12,000 metric tons of orange pulp and peels were dumped onto a three-hectare stretch. After the court case, the Del Oro experiment was shut down and the outrage died down – but the old peels remained. Sixteen years later, in 2013, Timothy Treuer, a graduate student at Princeton was scouting out research topics and connected with one of the original ecologists on the ACG – Del Oro project. The idea came up to do a follow-up study on the effects the orange peels had had on the land – so Treuer traveled to Costa Rica. What he found nobody could have expected.

Image credits: Princeton University

“It was so completely overgrown with trees and vines that I couldn’t even see the 7-foot-long sign with bright yellow lettering marking the site that was only a few feet from the road,” said Treuer. “I knew we needed to come up with some really robust metrics to quantify exactly what was happening and to back up this eye-test, which was showing up at this place and realizing visually how stunning the difference was between fertilized and unfertilized areas.”

Image credits: Princeton University

The researcher left and came back in 2014 with a full team to study the lush, revitalized land. Treuer and his team noted there had been a three-fold increase in the richness of woody plant species, a 176 percent increase in aboveground woody biomass compared to the control area and significantly elevated levels of macro and micronutrients.

Image credits: Princeton University

“Plenty of environmental problems are produced by companies, which, to be fair, are simply producing the things people need or want,” said study co-author David Wilcove. “But an awful lot of those problems can be alleviated if the private sector and the environmental community work together. I’m confident we’ll find many more opportunities to use the ‘leftovers’ from industrial food production to bring back tropical forests. That’s recycling at its best.”

Image credits: Princeton University

The researchers proposed in their study that the peels had completely transformed the land’s fertility from barren lifeless soil into a thick, rich, loamy mixture. And that the orange peels probably had suppressed the growth of an invasive grass that was keeping the forest from flourishing. The rediscovery gives hope to other companies that there are ways to execute waste management in environmentally and ecologically- sound ways.

Image credits: Princeton University

The site of the orange peel deposit (L) and adjacent pastureland (R)

Image credits: Princeton University

129Kviews

Share on FacebookFor most of the millions of years we humans have existed, our food waste products were dumped where it was consumed. Then we amassed more knowledge, moved into cities and got really good at organizing trhing - or so we thought - and la voilá: no more garbage laying around, the landfill was born. Then we bacame very many, too many for the good of our planet, and turned more and more land into crop production and now, for the most part, we take the nutrients out of the soil but we do not put it back in. We dump all the useful food leftovers in the city dump. There are individuals composting, and there are more and more communities composting, but it should be the norm, not the exeption.

For most of the millions of years we humans have existed, our food waste products were dumped where it was consumed. Then we amassed more knowledge, moved into cities and got really good at organizing trhing - or so we thought - and la voilá: no more garbage laying around, the landfill was born. Then we bacame very many, too many for the good of our planet, and turned more and more land into crop production and now, for the most part, we take the nutrients out of the soil but we do not put it back in. We dump all the useful food leftovers in the city dump. There are individuals composting, and there are more and more communities composting, but it should be the norm, not the exeption.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

272

27